library(keras3)

.[.[train_data, train_labels], .[test_data, test_labels]] <-

dataset_imdb(num_words = 10000)4 Classification and regression

This chapter covers

- Your first examples of real-world machine learning workflows

- Handling binary and categorical classification problems

- Handling continuous regression problems

This chapter is designed to get you started with using neural networks to solve real problems. You’ll consolidate the knowledge you gained from chapters 2 and 3, and you’ll apply what you’ve learned to three new tasks covering the three most common use cases of neural networks—binary classification, categorical classification, and scalar regression:

- Classifying movie reviews as positive or negative (binary classification)

- Classifying newswires by topic (categorical classification)

- Estimating the price of a house, given real estate data (scalar regression)

These examples will be your first contact with end-to-end machine learning workflows: you’ll be introduced to data preprocessing, basic model architecture principles, and model evaluation. By the end of this chapter, you’ll be able to use neural networks to handle simple classification and regression tasks over vector data. You’ll then be ready to start building a more principled, theory-driven understanding of machine learning in chapter 5.

Classification and regression involve many specialized terms. You’ve come across some of them in earlier examples, and you’ll see more of them in future chapters. They have precise, machine-learning-specific definitions, and you should be familiar with them:

- Sample or input—One data point that goes into a model.

- Prediction or output—What comes out of the model.

- Target—The truth. What the model should ideally have predicted, according to an external source of data.

- Prediction error or loss value—A measure of the distance between a model’s prediction and the target.

- Classes—A set of possible labels to choose from in a classification problem. For example, when classifying cat and dog pictures, “

dog” and “cat” are the two classes. - Label—A specific instance of a class annotation in a classification problem. For instance, if picture #1234 is annotated as containing the class “

dog,” then “dog” is a label of picture #1234. - Ground truth or annotations—All targets for a dataset, typically collected by humans.

- Binary classification—A classification task where each input sample should be categorized into two exclusive categories.

- Categorical classification or multiclass classification—A classification task where each input sample should be categorized into more than two categories: for instance, classifying handwritten digits.

- Multilabel classification—A classification task where each input sample can be assigned multiple labels. For instance, a given image may contain both a cat and a dog and should be annotated with both the “

cat” label and the “dog” label. The number of labels per image is usually variable. - Scalar regression—A task where the target is a continuous scalar value. Predicting house prices is a good example: the different target prices form a continuous space.

- Vector regression—A task where the target is a set of continuous values: for example, a continuous vector. If you’re doing regression against multiple values (such as the coordinates of a bounding box in an image), then you’re doing vector regression.

- Mini-batch or just batch—A small set of samples (typically between 8 and 128) that are processed simultaneously by the model. The number of samples is often a power of 2 to facilitate memory allocation on GPUs. When training, a mini-batch is used to compute a single gradient-descent update applied to the weights of the model.

4.1 Classifying movie reviews: A binary classification example

Two-class classification, or binary classification, is one of the most common kinds of machine learning problems. In this example, you’ll learn to classify movie reviews as positive or negative, based on the text content of the reviews.

4.1.1 The IMDb dataset

We’ll work with the IMDb dataset: a set of 50,000 highly polarized reviews from the Internet Movie Database. They’re split into 25,000 reviews for training and 25,000 reviews for testing, each set consisting of 50% negative and 50% positive reviews.

Just like the MNIST dataset, the IMDb dataset comes packaged with Keras. It has already been preprocessed: the reviews (sequences of words) have been turned into sequences of integers, where each integer stands for a specific word in a dictionary. This enables us to focus on model building, training, and evaluation. In chapter 14, you’ll learn how to process raw text input from scratch.

The following code will load the dataset (when you run it the first time, about 80 MB of data will be downloaded to your machine).

.[<-) operator

The datasets built into Keras are all nested lists of training and test data. Here, we use the multiassignment operator (.[<-) from the dotty package to unpack the list into a set of distinct variables. This could equally be written as follows:

imdb <- dataset_imdb(num_words = 10000)

train_data <- imdb$train$x

train_labels <- imdb$train$y

test_data <- imdb$test$x

test_labels <- imdb$test$yThe multiassignment version is preferable because it’s more compact. The dotty multiassignment .[<- method is automatically available whenever the keras3 package is attached.

The argument num_words = 10000 means we’ll only keep the top 10,000 most frequently occurring words in the training data. Rare words will be discarded. This allows you to work with vector data of manageable size. If we didn’t set this limit, we’d be working with 88,585 unique words in the training data, which is unnecessarily large. Many of these words only occur in a single sample, and thus can’t be meaningfully used for classification.

The variables train_data and test_data are lists of reviews; each review is a vector of word indices (encoding a sequence of words). train_labels and test_labels are vectors of 0s and 1s, where 0 stands for negative and 1 stands for positive:

str(train_data)List of 25000

$ : int [1:218] 1 14 22 16 43 530 973 1622 1385 65 ...

$ : int [1:189] 1 194 1153 194 8255 78 228 5 6 1463 ...

$ : int [1:141] 1 14 47 8 30 31 7 4 249 108 ...

$ : int [1:550] 1 4 2 2 33 2804 4 2040 432 111 ...

$ : int [1:147] 1 249 1323 7 61 113 10 10 13 1637 ...

[list output truncated]max(sapply(train_data, max))[1] 9999str(train_labels) int [1:25000] 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 ...Because we’re restricting ourselves to the top 10,000 most frequent words, no word index will exceed 10,000:

1word_index <- dataset_imdb_word_index()

str(word_index)

max(unlist(word_index))

stopifnot(all(

1:max(unlist(word_index)) == sort(unlist(word_index))

))- 1

-

word_indexis a named list mapping each word to a unique integer index.

List of 88584

$ fawn : int 34701

$ tsukino : int 52006

$ nunnery : int 52007

$ sonja : int 16816

$ vani : int 63951

[list output truncated]

[1] 88584For kicks, let’s quickly decode one of these reviews back to English words.

- 1

- Sorts the words by their index to create a lookup table

- 2

-

Indices 0, 1, 2, and 3 are reserved for “

padding,” “start of sequence,” “unknown,” and “unused.” - 3

-

Appends the words so that a word with

word_indexvaluekis encoded ask + 3in the dataset (and stored at positionk + 4in this R lookup vector) - 4

-

Decodes the review by mapping token IDs to words; adds 1 so that token ID

tmaps to lookup-table positiont + 1(R uses 1-based indexing)

Let’s take a look at the result:

decode_imdb_words(head(train_data[[1]], 32)) |>

strwrap() |> cat(sep = "\n")<start-of-sequence> this film was just brilliant casting location

scenery story direction everyone's really suited the part they

played and you could just imagine being there robert <unknown> is

an amazing actor andNote that a start token has been prefixed to each review.

4.1.2 Preparing the data

We can’t feed lists of integers directly into a neural network. They all have different lengths, and a neural network expects to process contiguous batches of data. We have to turn our lists into tensors. There are two ways to do that:

Pad our lists so that they all have the same length, turn them into an integer tensor of shape

(samples, max_length), and start our model with a layer capable of handling such integer tensors (theEmbeddinglayer, which we’ll cover in detail later in the book).Multi-hot encode our lists to turn them into vectors of 0s and 1s reflecting the presence or absence of all possible words. This would mean, for instance, turning the sequence

[8, 5]into a 10,000-dimensional vector that would be all 0s except for indices 5 and 8, which would be 1s.

Let’s go with the latter solution to vectorize the data. When done manually, the process looks like the following.

multi_hot_encode <- function(sequences, num_classes) {

1 results <- matrix(0, nrow = length(sequences), ncol = num_classes)

for (i in seq_along(sequences)) {

2 results[i, sequences[[i]] + 1] <- 1

}

results

}

3x_train <- multi_hot_encode(train_data, num_classes = 10000)

4x_test <- multi_hot_encode(test_data, num_classes = 10000)- 1

-

Creates an all-zero matrix of shape

(length(sequences), num_classes) - 2

-

Sets specific columns of row

results[i, ]to 1s - 3

- Vectorized training data

- 4

- Vectorized test data

Here’s what the samples look like now:

str(x_train) num [1:25000, 1:10000] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...In addition to vectorizing the input sequences, we should also vectorize their labels, which is straightforward. Our labels are already vectors, so we just convert the type from integers to (floating-point) numeric:

y_train <- as.numeric(train_labels)

y_test <- as.numeric(test_labels)Now the data is ready to be fed into a neural network.

4.1.3 Building the model

The input data is vectors, and the labels are scalars (1s and 0s): this is one of the simplest problem setups you’ll ever encounter. A type of model that performs well on such a problem is a plain stack of densely connected (Dense) layers with relu activations.

There are two key architecture decisions to be made about such a stack of Dense layers:

- How many layers to use

- How many units to choose for each layer

In chapter 5, you’ll learn formal principles to guide you in making these choices. For the time being, you’ll have to trust us with the following architecture choice:

- Two intermediate layers with 16 units each

- A third layer that will output the scalar prediction regarding the sentiment of the current review

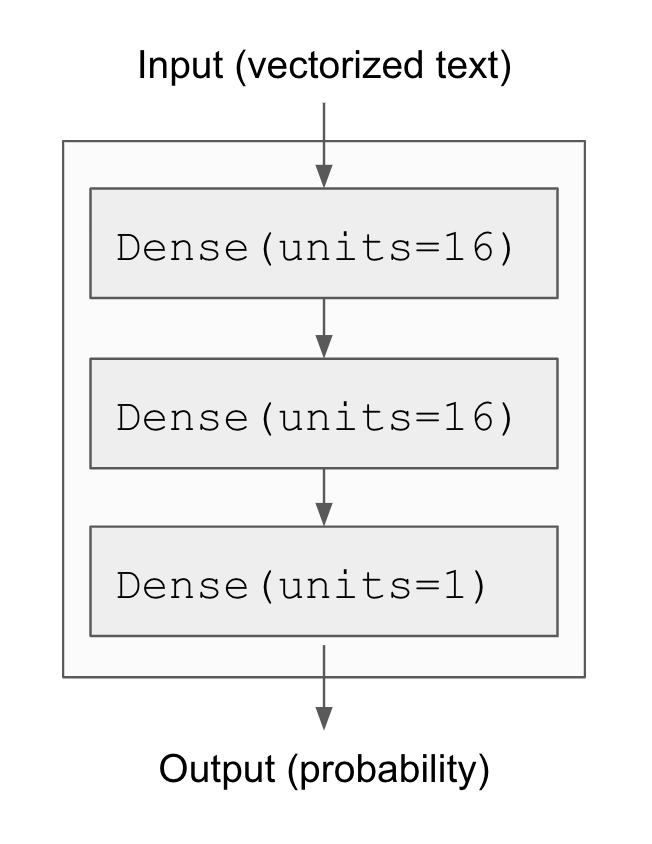

Figure 4.1 shows what the model looks like. Here’s the Keras implementation, similar to the MNIST example you saw previously.

model <- keras_model_sequential() |>

layer_dense(16, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(16, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(1, activation = "sigmoid")The first argument being passed to each Dense layer is the number of units in the layer: the dimensionality of the representation space of the layer. Recall from chapters 2 and 3 that each such Dense layer with a relu activation implements the following chain of tensor operations:

output = relu(dot(input, W) + b)Having 16 units means the weight matrix W will have shape (input_dimension, 16): the dot product with W will project the input data onto a 16-dimensional representation space (and then we’ll add the bias vector b and apply the relu operation). You can intuitively understand the dimensionality of the representation space as “how much freedom you’re allowing the model to have when learning internal representations.” Having more units (a higher-dimensional representation space) allows our model to learn more complex representations, but it makes the model more computationally expensive and may lead to learning unwanted patterns (patterns that will improve performance on the training data but not on the test data).

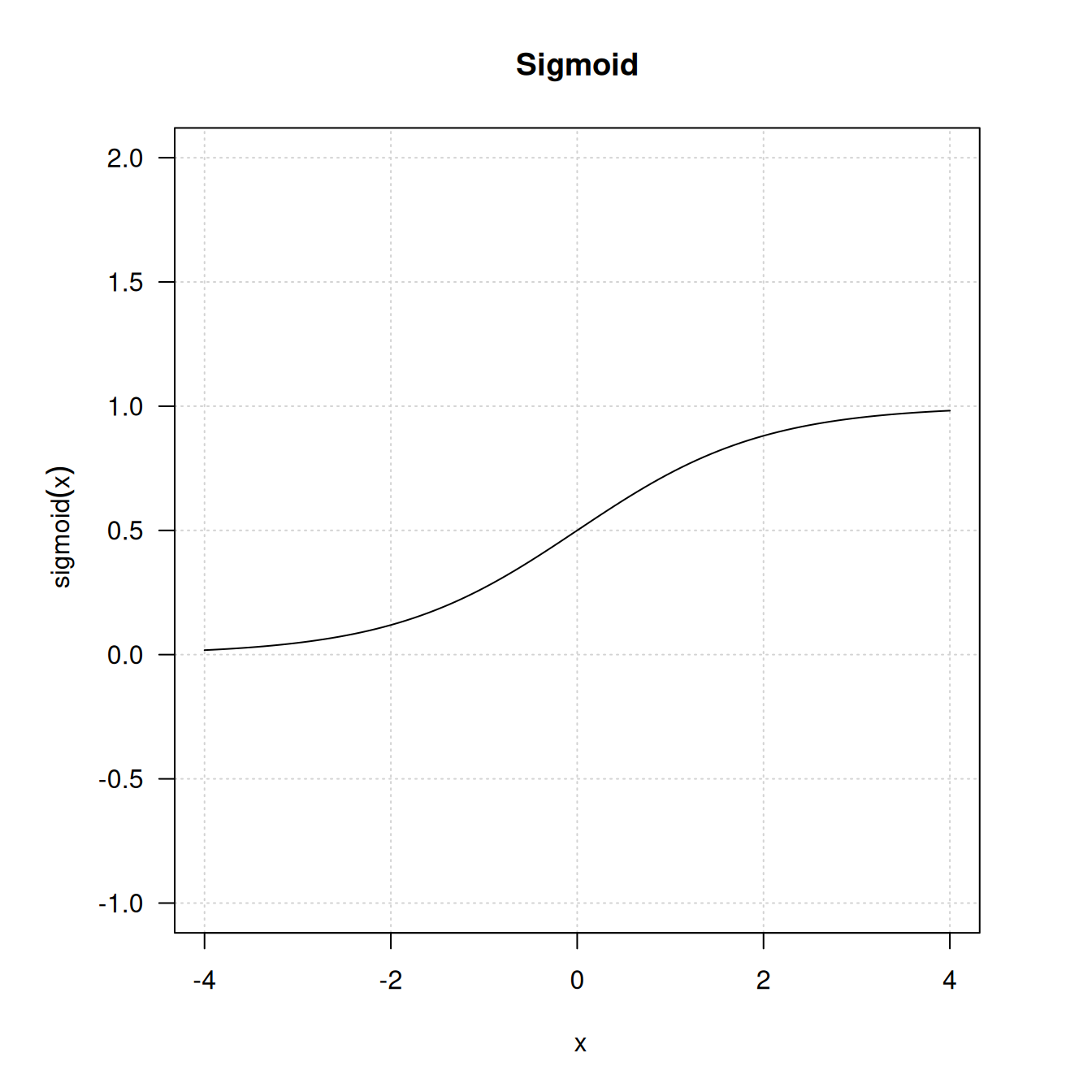

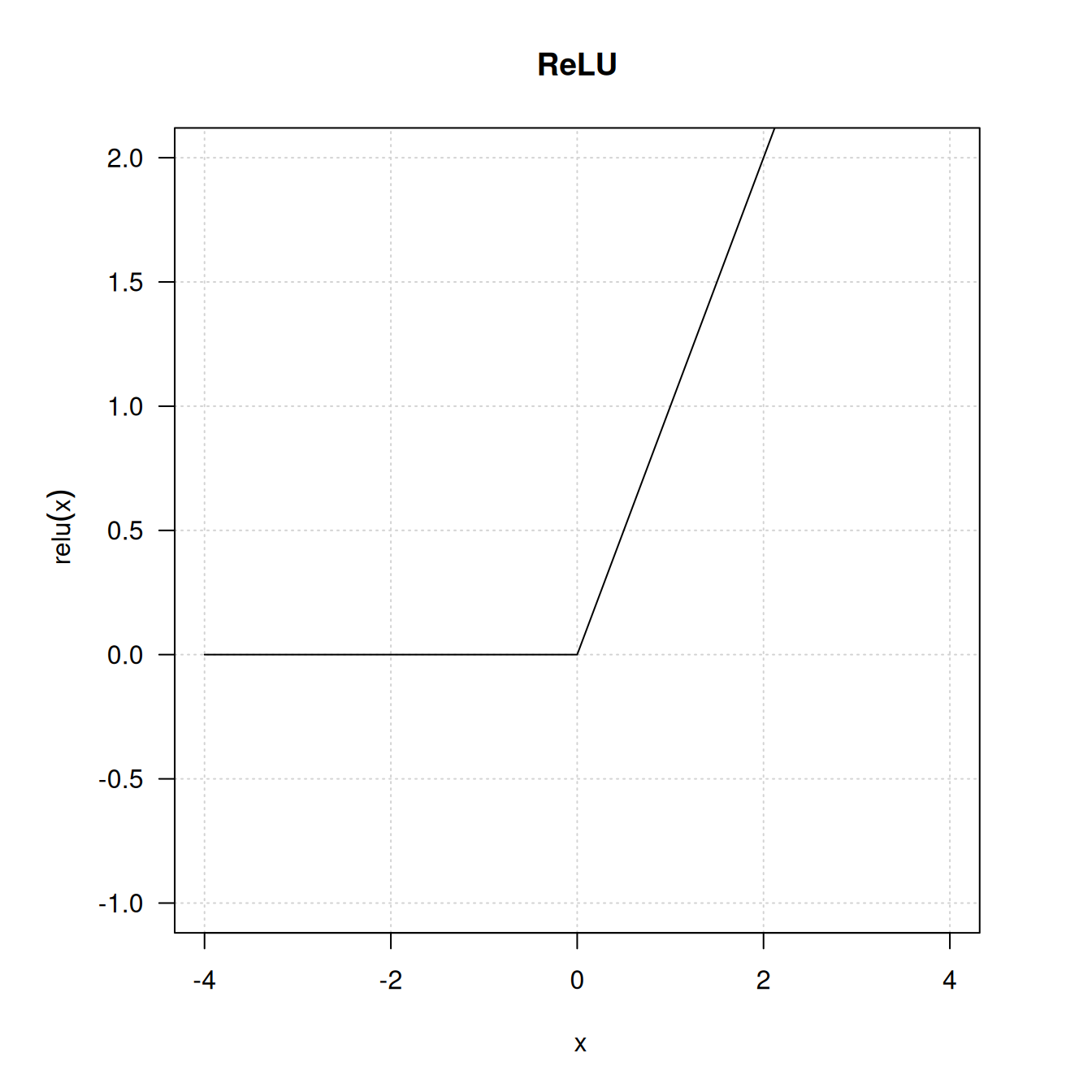

The intermediate layers use relu as their activation function, and the final layer uses a sigmoid activation to output a probability (a score between 0 and 1, indicating how likely the review is to be positive). A relu (rectified linear unit) is a function meant to zero out negative values (see figure 4.2), whereas a sigmoid “squashes” arbitrary values into the [0, 1] interval (see figure 4.3), outputting something that can be interpreted as a probability.

Without an activation function like relu (also called a nonlinearity), the Dense layer would consist of two linear operations—a dot product and an addition:

output <- dot(input, W) + bSo the layer could only learn linear transformations (affine transformations) of the input data: the hypothesis space of the layer would be the set of all possible linear transformations of the input data into a 16-dimensional space. Such a hypothesis space is too restricted and wouldn’t benefit from multiple layers of representations because a deep stack of linear layers would still implement a linear operation: adding more layers wouldn’t extend the hypothesis space (as you saw in chapter 2).

To get access to a much richer hypothesis space that would benefit from deep representations, we need a nonlinearity or activation function. relu is the most popular activation function in deep learning, but there are many other candidates, which all come with similarly strange names: prelu, elu, and so on.

Finally, we need to choose a loss function and an optimizer. Because we’re facing a binary classification problem and the output of our model is a probability (we end our model with a single-unit layer with a sigmoid activation), it’s best to use the binary_crossentropy loss. It isn’t the only viable choice: we could use, for instance, mean_squared_error. But cross-entropy is usually the best choice when we’re dealing with models that output probabilities. Cross-entropy is a quantity from the field of Information Theory that measures the distance between probability distributions or, in this case, between the ground-truth distribution and our predictions.

As for the choice of the optimizer, we’ll go with adam, which is usually a good default choice for virtually any problem. Here’s the step where we configure the model with the adam optimizer and the binary_crossentropy loss function. Note that we’ll also monitor accuracy during training.

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)4.1.4 Validating the approach

As you learned in chapter 3, a deep learning model should never be evaluated on its training data—it’s standard practice to use a validation set to monitor the accuracy of the model during training. Here, we’ll create a validation set by setting apart 10,000 samples from the original training data.

You might ask: why not simply use the test data to evaluate the model? That seems like it would be easier. The reason is that we’ll want to use the results we get on the validation set to inform our next choices to improve training: for instance, our choice of what model size to use or how many epochs to train for. When we start doing this, our validation scores stop being an accurate reflection of the performance of the model on brand-new data, because the model has been deliberately modified to perform better on the validation data. It’s good to keep a set of never-before-seen samples that we can use to perform the final evaluation round in a completely unbiased way, and that’s exactly what the test set is. We’ll talk more about this in the next chapter.

val_indices <- 1:10000

x_val <- x_train[val_indices, ]

partial_x_train <- x_train[-val_indices, ]

y_val <- y_train[val_indices]

partial_y_train <- y_train[-val_indices]We’ll now train the model for 20 epochs (20 iterations over all samples in the training data) in mini-batches of 512 samples. At the same time, we’ll monitor loss and accuracy on the 10,000 samples that we set apart. We do so by passing the validation data as the validation_data argument to fit().

history <- model |> fit(

partial_x_train, partial_y_train,

epochs = 20,

batch_size = 512,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val)

)validation_split argument

Instead of manually splitting out validation data from our training data and passing it as the validation_data argument, we can also use the validation_split argument in fit(). It specifies a fraction of the training data to use as validation data, like this:

history <- model |> fit(

x_train, y_train,

epochs = 20,

batch_size = 512,

validation_split = 0.2

)In this example, 20% of the samples in x_train and y_train are being held out from training and used as validation data.

On CPU, this will take less than 2 seconds per epoch—training is over in 20 seconds. At the end of every epoch, there is a slight pause as the model computes its loss and accuracy on the 10,000 samples of the validation data.

Note that the call to fit() returns a keras_training_history object, as you saw in chapter 3. This object has a member metrics, which is a named list containing data about everything that happened during training. Let’s look at it:

str(history$metrics)List of 4

$ accuracy : num [1:20] 0.77 0.892 0.923 0.945 0.96 ...

$ loss : num [1:20] 0.583 0.348 0.234 0.173 0.135 ...

$ val_accuracy: num [1:20] 0.851 0.883 0.89 0.889 0.886 ...

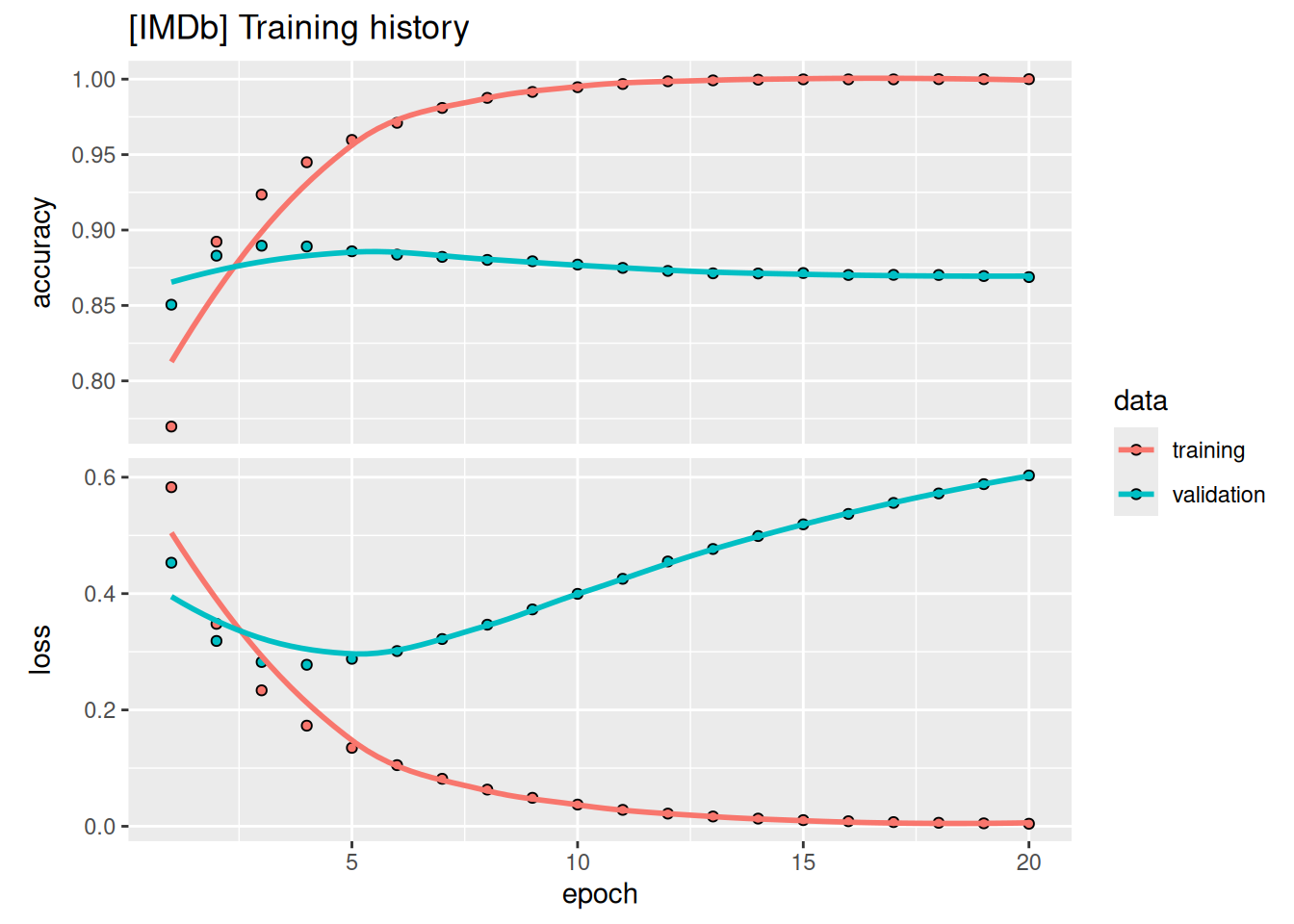

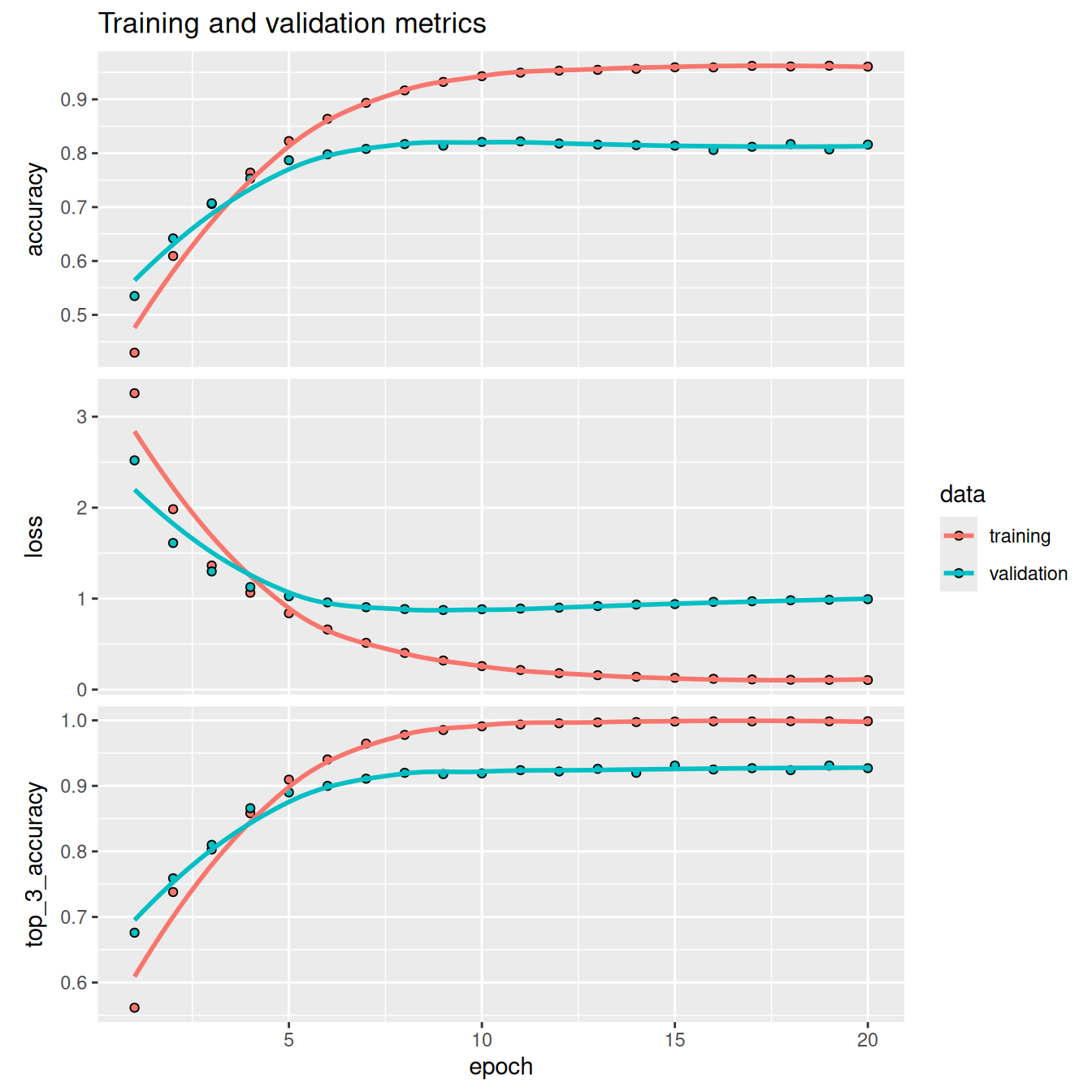

$ val_loss : num [1:20] 0.453 0.319 0.282 0.278 0.288 ...The list contains four entries: one per metric that was being monitored during training and during validation. Let’s plot the training and validation losses and accuracies; see figure 4.4. Note that your own results may vary slightly due to a different random initialization of your model.

library(ggplot2)

plot(history) + ggtitle("[IMDb] Training history")As you can see, the training loss decreases with every epoch, and the training accuracy increases with every epoch. That’s what we would expect when running gradient-descent optimization: the quantity we’re trying to minimize should decrease with every iteration. But that isn’t the case for the validation loss and accuracy: they seem to peak at the fourth epoch. This is an example of what we warned against earlier: a model that performs better on the training data isn’t necessarily a model that will do better on data it has never seen before. In precise terms, what you’re seeing is overfitting: after the fourth epoch, we’re over-optimizing on the training data, and we end up learning representations that are specific to the training data and don’t generalize to data outside of the training set.

In this case, to prevent overfitting, we could stop training after four epochs. In general, we can use a range of techniques to mitigate overfitting, which we’ll cover in chapter 5.

Let’s train a new model from scratch for four epochs and then evaluate it on the test data.

model <- keras_model_sequential() |>

layer_dense(16, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(16, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(1, activation = "sigmoid")

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

metrics = "accuracy"

)

model |> fit(x_train, y_train, epochs = 4, batch_size = 512)

results <- model |> evaluate(x_test, y_test)The final results are as follows:

1str(results)- 1

- The loss and accuracy on the test set

List of 2

$ accuracy: num 0.876

$ loss : num 0.327This fairly naive approach achieves an accuracy of 88%. With state-of-the-art approaches, you should be able to get close to 95%.

4.1.5 Using a trained model to generate predictions on new data

After having trained a model, we’ll want to use it in a practical setting. We can generate the likelihood of reviews being positive by using the predict method, as you learned in chapter 3:

preds <- model |> predict(x_test)

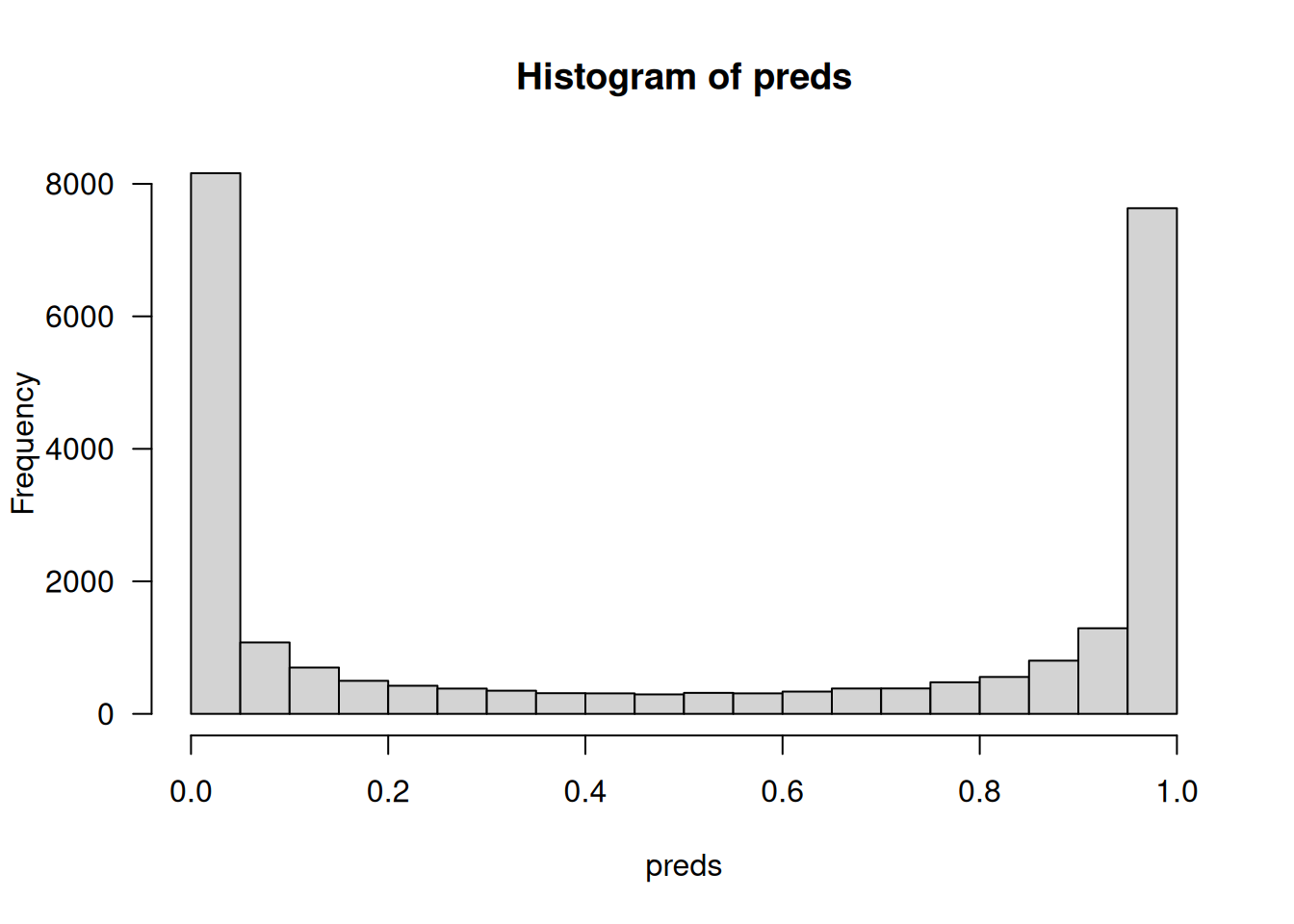

str(preds) num [1:25000, 1] 0.133 1 0.599 0.921 0.973 ...As you can see in figure 4.5, the model is confident for some samples (close to 1 or 0) but less confident for others (close to 0.5).

4.1.6 Further experiments

The following experiments will help convince you that the architecture choices we made are all fairly reasonable, although there’s still room for improvement:

We used two representation layers before the final classification layer. Try using one or three representation layers and see how doing so affects validation and test accuracy.

Try using layers with more units or fewer units: 32 units, 64 units, and so on.

Try using the

mean_squared_errorloss function instead ofbinary_crossentropy.Try using the

tanhactivation (an activation that was popular in the early days of neural networks) instead ofrelu.

4.1.7 Wrapping up

Here’s what you should take away from this example:

You usually need to do quite a bit of preprocessing on the raw data to be able to feed it, as tensors, into a neural network. Sequences of words can be encoded as binary vectors, but there are other encoding options, too.

Stacks of

Denselayers withreluactivations can solve a wide range of problems (including sentiment classification), and you’ll use them frequently.In a binary classification problem (two output classes), your model should end with a

Denselayer with one unit and asigmoidactivation: the output of your model should be a scalar between 0 and 1, encoding a probability.With such a scalar sigmoid output on a binary classification problem, the loss function you should use is

binary_crossentropy.The

adamoptimizer is generally a good enough choice, whatever your problem. That’s one less thing for you to worry about.As they get better on their training data, neural networks eventually start overfitting and obtain increasingly worse results on data they’ve never seen before. Be sure to always monitor performance on data that is outside of the training set!

4.2 Classifying newswires: A multiclass classification example

In the previous section, you saw how to classify vector inputs into two mutually exclusive classes using a densely connected neural network. But what happens when you have more than two classes?

In this section, we’ll build a model to classify Reuters newswires into 46 mutually exclusive topics. Because we have many classes, this problem is an instance of multiclass classification; and because each data point should be classified into only one category, the problem is more specifically an instance of single-label multiclass classification. If each data point could belong to multiple categories (in this case, topics), we’d be facing a multilabel multiclass classification problem.

4.2.1 The Reuters dataset

We’ll work with the Reuters dataset, a set of short newswires and their topics, published by Reuters in 1986. It’s a simple, widely used toy dataset for text classification. There are 46 different topics; some topics are more represented than others, but each topic has at least 10 examples in the training set.

Like IMDb and MNIST, the Reuters dataset comes packaged as part of Keras. Let’s take a look.

.[.[train_data, train_labels], .[test_data, test_labels]] <-

dataset_reuters(num_words = 10000)As with the IMDb dataset, the argument num_words=10000 restricts the data to the 10,000 most frequently occurring words found in the data.

We have 8,982 training examples and 2,246 test examples. As with the IMDb reviews, each example is a vector of integers (word indices):

str(train_data)List of 8982

$ : int [1:87] 1 2 2 8 43 10 447 5 25 207 ...

$ : int [1:56] 1 3267 699 3434 2295 56 2 7511 9 56 ...

$ : int [1:139] 1 53 12 284 15 14 272 26 53 959 ...

$ : int [1:224] 1 4 686 867 558 4 37 38 309 2276 ...

$ : int [1:101] 1 8295 111 8 25 166 40 638 10 436 ...

[list output truncated]str(test_data)List of 2246

$ : int [1:145] 1 4 1378 2025 9 697 4622 111 8 25 ...

$ : int [1:745] 1 2768 283 122 7 4 89 544 463 29 ...

$ : int [1:228] 1 4 309 2276 4759 5 2015 403 1920 33 ...

$ : int [1:172] 1 2 2 65 9 249 1096 8 16 515 ...

$ : int [1:187] 1 470 354 2 4231 62 2373 509 1687 5138 ...

[list output truncated]Here’s how to decode it back to words, in case you’re curious.

- 1

-

word_indexis a named list mapping each word to a unique integer index. - 2

- Sorts the words by their index to create a lookup table

- 3

-

Indices 0, 1, 2, and 3 are reserved for “

padding,” “start of sequence,” “unknown,” and “unused.” - 4

-

Appends the words so that a word with

word_indexvaluekis encoded ask + 3in the dataset (and stored at positionk + 4in this R lookup vector) - 5

-

Decodes the review by mapping token IDs to words; adds 1 so that token ID

tmaps to lookup-table positiont + 1(R uses 1-based indexing)

The label associated with an example is an integer between 0 and 45—a topic index:

str(train_labels) int [1:8982] 3 4 3 4 4 4 4 3 3 16 ...4.2.2 Preparing the data

We can vectorize the data with the exact same code as in the previous example.

- 1

- Vectorized training data

- 2

- Vectorized test data

To vectorize the labels, there are two possibilities: we can leave the labels untouched as integers, or we can use one-hot encoding. One-hot encoding is a widely used format for categorical data, also called categorical encoding. In this case, one-hot encoding of the labels consists of embedding each label as an all-0 vector with a 1 in place of the label index. Here’s an example.

one_hot_encode <- function(labels, num_classes = 46) {

results <- matrix(0, nrow = length(labels), ncol = num_classes)

for (i in seq_along(labels)) {

1 label_position <- labels[[i]] + 1

results[i, label_position] <- 1

}

results

}

2y_train <- one_hot_encode(train_labels)

3y_test <- one_hot_encode(test_labels)- 1

- Adds 1 to the labels, because labels are 0-based

- 2

- Vectorized training labels

- 3

- Vectorized test labels

Note that there is a built-in way to do this in Keras:

y_train <- to_categorical(train_labels)

y_test <- to_categorical(test_labels)4.2.3 Building the model

This topic classification problem looks similar to the previous movie review classification problem: in both cases, we’re trying to classify short snippets of text. But there is a new constraint here: the number of output classes has gone from 2 to 46. The dimensionality of the output space is much larger.

In a stack of Dense layers like those we’ve been using, each layer can only access information present in the output of the previous layer. If one layer drops some information relevant to the classification problem, this information can never be recovered by later layers: each layer can potentially become an information bottleneck. In the previous example, we used 16-dimensional intermediate layers, but a 16-dimensional space may be too limited to learn to separate 46 different classes: such small layers may act as information bottlenecks, permanently dropping relevant information.

For this reason, we’ll use larger intermediate layers. Let’s go with 64 units.

model <- keras_model_sequential() |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(46, activation = "softmax")There are two other things to note about this architecture:

We end the model with a

Denselayer of size 46. This means for each input sample, the network will output a 46-dimensional vector. Each entry in this vector (each dimension) will encode a different output class.The last layer uses a

softmaxactivation. You saw this pattern in the MNIST example. It means the model will output a probability distribution over the 46 different output classes: for every input sample, the model will produce a 46-dimensional output vector, whereoutput[i]is the probability that the sample belongs to classi. The 46 scores will sum to 1.

The best loss function to use in this case is categorical_crossentropy. It measures the distance between two probability distributions: here, between the probability distribution outputted by the model and the true distribution of the labels. By minimizing the distance between these two distributions, we train the model to output something as close as possible to the true labels.

Like last time, we’ll also monitor accuracy. However, accuracy is a bit of a crude metric in this case: if the model has the correct class as its second choice for a given sample, with an incorrect first choice, the model will still have an accuracy of zero on that sample—even though such a model would be much better than a random guess. A more nuanced metric in this case is top-k accuracy, such as top-3 or top-5 accuracy. It measures whether the correct class was among the top k predictions of the model. Let’s add top-3 accuracy to our model.

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = c(

"accuracy",

metric_top_k_categorical_accuracy(k = 3, name = "top_3_accuracy")

)

)4.2.4 Validating the approach

Let’s set apart 1,000 samples in the training data to use as a validation set.

val_indices <- 1:1000

x_val <- x_train[val_indices,]

partial_x_train <- x_train[-val_indices,]

y_val <- y_train[val_indices,]

partial_y_train <- y_train[-val_indices,]Now, let’s train the model for 20 epochs.

history <- model |> fit(

partial_x_train, partial_y_train,

epochs = 20,

batch_size = 512,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val)

)And finally, let’s display its loss and accuracy curves (see figure 4.6).

plot(history) + ggtitle("Training and validation metrics")The model begins to overfit after nine epochs. Let’s train a new model from scratch for nine epochs and then evaluate it on the test set.

model <- keras_model_sequential() |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(46, activation = "softmax")

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = "accuracy"

)

model |> fit(x_train, y_train, epochs = 9, batch_size = 512)

results <- model |> evaluate(x_test, y_test)Here are the final results:

str(results)List of 2

$ accuracy: num 0.792

$ loss : num 0.917This approach reaches an accuracy of approximately 80%. With a balanced binary classification problem, the accuracy reached by a purely random classifier would be 50%. But in this case, we have 46 classes, and they may not be equally represented. What would be the accuracy of a random baseline? We can try quickly implementing one to check this empirically:

mean(test_labels == sample(test_labels))[1] 0.1883348As you can see, a random classifier would score around 19% classification accuracy, so the results of our model seem pretty good in that light.

4.2.5 Generating predictions on new data

Calling the model’s predict() method on new samples returns a class probability distribution over all 46 topics for each sample. Let’s generate topic predictions for all of the test data:

predictions <- model |> predict(x_test)Each entry in predictions is a vector of length 46:

str(predictions) num [1:2246, 1:46] 0.0001504 0.0009345 0.0038792 0.000946 0.0000543 ...The coefficients in this vector sum to 1, as they form a probability distribution:

sum(predictions[1, ])[1] 1envir::import_from(dplyr, near)

all(near(1, rowSums(predictions), tol = 1e-6))[1] TRUEThe largest entry is the predicted class—the class with the highest probability:

which.max(predictions[1, ])[1] 44.2.6 A different way to handle the labels and the loss

We mentioned earlier that another way to encode the labels would be to leave them untouched as integer tensors, like this:

y_train <- train_labels

y_test <- test_labelsThe only thing this approach would change is the choice of the loss function. The loss function used in listing 4.22, categorical_crossentropy, expects the labels to follow a categorical encoding. With integer labels, we should use sparse_categorical_crossentropy:

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "sparse_categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = "accuracy"

)This new loss function is still mathematically the same as categorical_crossentropy; it just has a different interface.

4.2.7 The importance of having sufficiently large intermediate layers

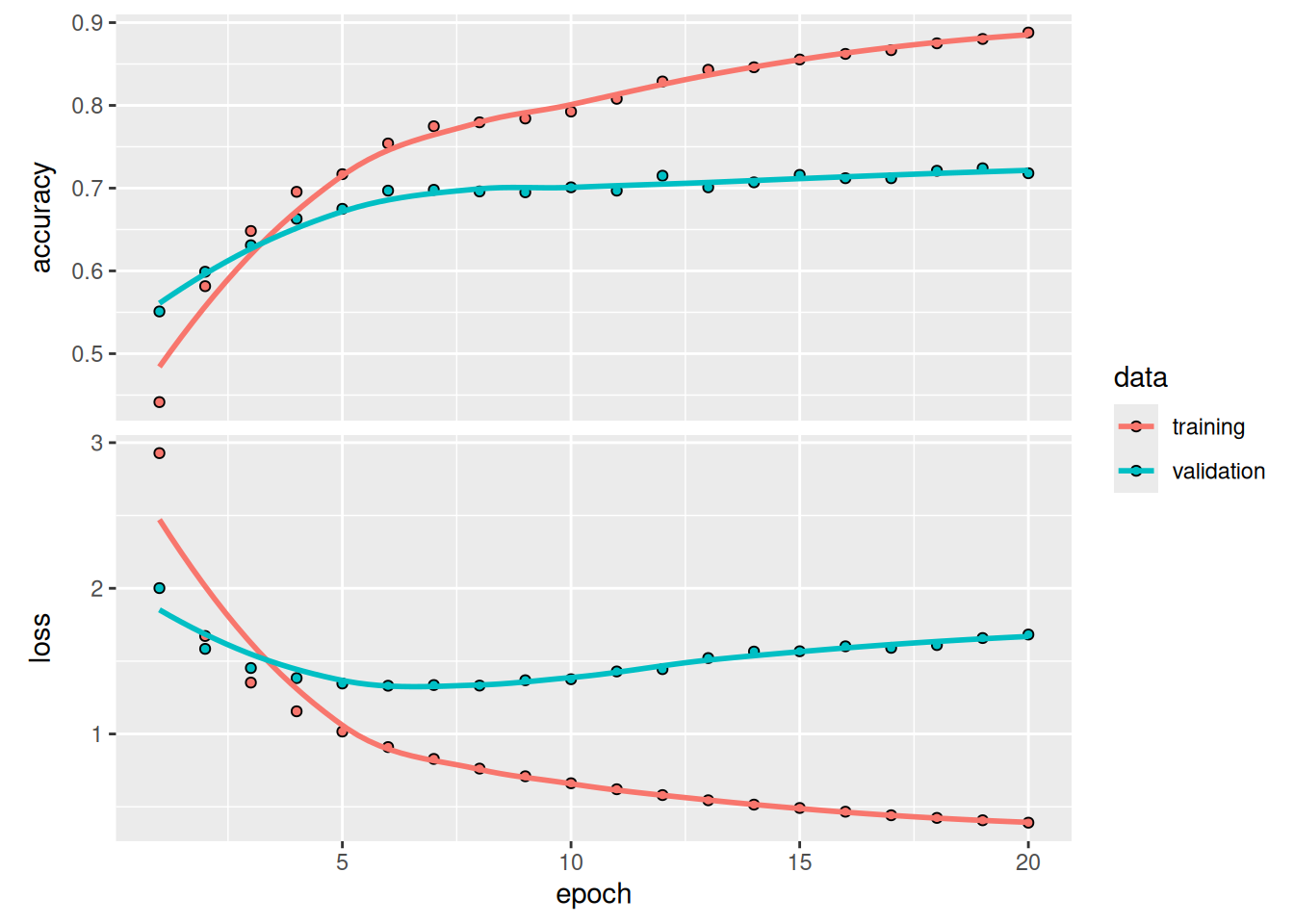

We mentioned earlier that because the final outputs are 46-dimensional, we should avoid intermediate layers with much fewer than 46 units. Now let’s see what happens when we introduce an information bottleneck by having intermediate layers that are significantly less than 46-dimensional: for example, 4-dimensional.

model <- keras_model_sequential() |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(4, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(46, activation = "softmax")

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = "accuracy"

)

history <- model |> fit(

partial_x_train, partial_y_train,

epochs = 20,

batch_size = 128,

validation_data = list(x_val, y_val)

)As shown in figure 4.7, the model now peaks at approximately 71% validation accuracy, an 8% absolute drop. This drop is mostly due to the fact that we’re trying to compress a lot of information (enough information to recover the separation hyperplanes of 46 classes) into an intermediate space that is too low-dimensional. The model is able to cram most of the necessary information into these four-dimensional representations, but not all of it.

4.2.8 Further experiments

As in the previous example, we encourage you to try the following experiments to train your intuition about the kind of configuration decisions you have to make with such models:

- Try using larger or smaller layers: 32 units, 128 units, and so on.

- We used two intermediate layers before the final

softmaxclassification layer. Try using a single intermediate layer, or three intermediate layers.

4.2.9 Wrapping up

Here’s what you should take away from this example:

If you’re trying to classify data points among N classes, your model should end with a

Denselayer of size N.In a single-label, multiclass classification problem, your model should end with a

softmaxactivation so that it will output a probability distribution over the N output classes.Categorical cross-entropy is almost always the loss function you should use for such problems. It minimizes the distance between the probability distributions output by the model and the true distribution of the targets.

There are two ways to handle labels in multiclass classification:

- Encoding the labels via categorical encoding (also known as one-hot encoding) and using

categorical_crossentropyas a loss function - Encoding the labels as integers and using the

sparse_categorical_crossentropyloss function

- Encoding the labels via categorical encoding (also known as one-hot encoding) and using

If you need to classify data into a large number of categories, avoid creating information bottlenecks in your model due to intermediate layers that are too small.

4.3 Predicting house prices: A regression example

The two previous examples were considered classification problems, where the goal was to predict a single discrete label of an input data point. Another common type of machine learning problem is regression, which consists of predicting a continuous value instead of a discrete label: for instance, predicting the temperature tomorrow given meteorological data, or predicting the time that a software project will take to complete given its specifications.

Don’t confuse regression and the algorithm logistic regression. Confusingly, logistic regression isn’t a regression algorithm—it’s a classification algorithm.

4.3.1 The California Housing Price dataset

We’ll attempt to predict the median price of homes in different areas of California, based on data from the 1990 census. Each data point in the dataset represents information about a “block group,” a group of homes located in the same area. You can think of it as a district. This dataset has two versions: the “small” version with just 600 districts and the “large” version with 20,640 districts. Let’s use the small version, because real-world datasets can often be tiny, and you need to know how to handle such cases.

For each district, we know

- The longitude and latitude of the approximate geographic center of the area.

- The median age of houses in the district.

- The population of the district. The districts are pretty small: the average population is 1,425.5.

- The total number of households.

- The median income of those households.

- The total number of rooms in the district, across all homes located there. This is typically in the low thousands.

- The total number of bedrooms in the district.

That’s eight variables in total (longitude and latitude count as two variables). The goal is to use these variables to predict the median value of the houses in the district. Let’s get started by loading the data.

.[.[train_data, train_targets], .[test_data, test_targets]] <-

1 dataset_california_housing(version = "small")- 1

-

Be sure to pass

version="small"to get the right dataset

Let’s look at the data:

str(train_data) num [1:480, 1:8] -122 -122 -122 -122 -122 ...str(test_data) num [1:120, 1:8] -122 -122 -122 -122 -122 ...As you can see, we have 480 training samples and 120 test samples, each with 8 numerical features. The targets are the median values of homes in the district considered, in dollars:

str(train_targets) num [1:480(1d)] 228400 132900 60000 95200 107000 ...The prices are between $60,000 and $500,000. If that sounds cheap, remember that this was in 1990, and these prices aren’t adjusted for inflation.

4.3.2 Preparing the data

It would be problematic to feed into a neural network values that all take wildly different ranges. The model might be able to automatically adapt to such heterogeneous data, but it would definitely make learning more difficult. A widespread best practice to deal with such data is to do feature-wise normalization: for each feature in the input data (a column in the input data matrix), we subtract the mean of the feature and divide by the standard deviation, so that the feature is centered around 0 and has a unit standard deviation. This is easily done in R.

train_mean <- apply(train_data, 2, mean)

train_sd <- apply(train_data, 2, sd)

x_train <- scale(train_data, center = train_mean, scale = train_sd)

x_test <- scale(test_data, center = train_mean, scale = train_sd)Note that the quantities used for normalizing the test data are computed using the training data. You should never use in your workflow any quantity computed on the test data, even for something as simple as data normalization.

In addition, we should also scale the targets. Our normalized inputs have their value in a small range close to 0, and our model’s weights are initialized with small random values. This means our model’s prediction will also be small values when we start training. If the targets are in the range 60,000–500,000, the model will need very large weight values to output them. With a small learning rate, it would take a very long time to get there. The simplest fix is to divide all target values by 100,000 so that the smallest target becomes 0.6 and the largest becomes 5. We can then convert the model’s predictions back to dollar values by multiplying them by 100,000.

y_train <- train_targets / 100000

y_test <- test_targets / 1000004.3.3 Building the model

Because so few samples are available, we’ll use a very small model with two intermediate layers, each with 64 units. In general, the less training data we have, the worse overfitting will be, and using a small model is one way to mitigate overfitting.

1get_model <- function() {

model <- keras_model_sequential() |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(64, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dense(1)

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "mean_squared_error",

metrics = "mean_absolute_error"

)

model

}- 1

- Because we’ll need to instantiate the same model multiple times, we use a function to construct it.

The model ends with a single unit and no activation: it will be a linear layer. This is a typical setup for scalar regression—a regression where we’re trying to predict a single continuous value. Applying an activation function would constrain the range the output can take; for instance, if we applied a sigmoid activation function to the last layer, the model could only learn to predict values between 0 and 1. Here, because the last layer is purely linear, the model is free to learn to predict values in any range.

Note that we compile the model with the mean_squared_error loss function: mean squared error (MSE), the square of the difference between the predictions and the targets. This is a widely used loss function for regression problems.

We’re also monitoring a new metric during training: mean absolute error (MAE). It’s the absolute value of the difference between the predictions and the targets. For instance, an MAE of 0.5 on this problem would mean our predictions were off by $50,000 on average (remember the target scaling of factor 100,000).

4.3.4 Validating the approach using K-fold validation

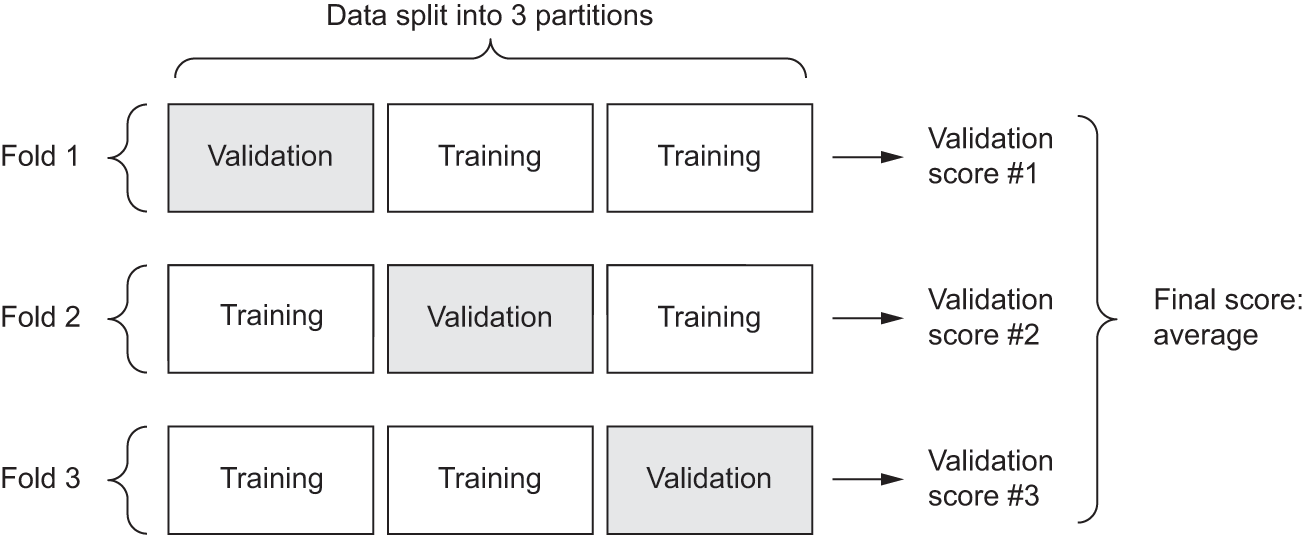

To evaluate our model while we keep adjusting its parameters (such as the number of epochs used for training), we could split the data into a training set and a validation set, as we did in the previous examples. But because we have so few data points, the validation set would be very small (for instance, about 100 examples). As a consequence, the validation scores might change a lot depending on which data points we chose to use for validation and which we chose for training: the validation scores might have a high variance with regard to the validation split. This would prevent us from reliably evaluating our model.

The best practice in such situations is to use K-fold cross-validation (see figure 4.8). It consists of splitting the available data into K partitions (typically K = 4 or 5), instantiating K identical models, and training each one on K – 1 partitions while evaluating on the remaining partition. The validation score for the model used is then the average of the K validation scores obtained. In terms of code, this is straightforward.

k <- 4

fold_id <- sample(rep(1:k, length.out = nrow(train_data)))

num_epochs <- 50

all_scores <- numeric(k)

for (i in 1:k) {

cat(sprintf("Processing fold #%i\n", i))

fold_val_indices <- which(fold_id == i)

1 fold_x_val <- x_train[fold_val_indices, ]

fold_y_val <- y_train[fold_val_indices]

2 fold_x_train <- x_train[-fold_val_indices, ]

fold_y_train <- y_train[-fold_val_indices]

3 model <- get_model()

4 model |> fit(

fold_x_train, fold_y_train,

epochs = num_epochs, batch_size = 16, verbose = 0

)

5 results <- model |> evaluate(fold_x_val, fold_y_val, verbose = 0)

all_scores[i] <- results$mean_absolute_error

}- 1

- Prepares the validation data: data from partition #k

- 2

- Prepares the training data: data from all other partitions

- 3

- Builds the Keras model (already compiled)

- 4

- Trains the model

- 5

- Evaluates the model on the validation data

Processing fold #1

Processing fold #2

Processing fold #3

Processing fold #4Running this with num_epochs <- 50 yields the following results:

round(all_scores, 3)[1] 0.336 0.294 0.266 0.268mean(all_scores)[1] 0.2910109The different runs do indeed show meaningfully different validation scores, from 0.266 to 0.336. The average (0.291) is a much more reliable metric than any single score—that’s the entire point of K-fold cross-validation. In this case, we’re off by $29,000 on average, which is significant considering that the prices range from $60,000 to $500,000.

Let’s try training the model a bit longer: 200 epochs. To keep a record of how well the model does at each epoch, we’ll modify the training loop to save the per-epoch validation score log.

k <- 4

num_epochs <- 200

all_mae_histories <- list()

for (i in 1:k) {

cat(sprintf("Processing fold #%i\n", i))

1 fold_val_indices <- which(fold_id == i)

fold_x_val <- x_train[fold_val_indices, ]

fold_y_val <- y_train[fold_val_indices]

2 fold_x_train <- x_train[-fold_val_indices, ]

fold_y_train <- y_train[-fold_val_indices]

3 model <- get_model()

4 history <- model |> fit(

fold_x_train, fold_y_train,

validation_data = list(fold_x_val, fold_y_val),

epochs = num_epochs, batch_size = 16, verbose = 0

)

mae_history <- history$metrics$val_mean_absolute_error

all_mae_histories[[i]] <- mae_history

}

all_mae_histories <- do.call(cbind, all_mae_histories)- 1

- Prepares the validation data: data from partition #k

- 2

- Prepares the training data: data from all other partitions

- 3

- Builds the Keras model (already compiled)

- 4

- Trains the model

Processing fold #1

Processing fold #2

Processing fold #3

Processing fold #4We can then compute the average of the per-epoch MAE scores for all folds.

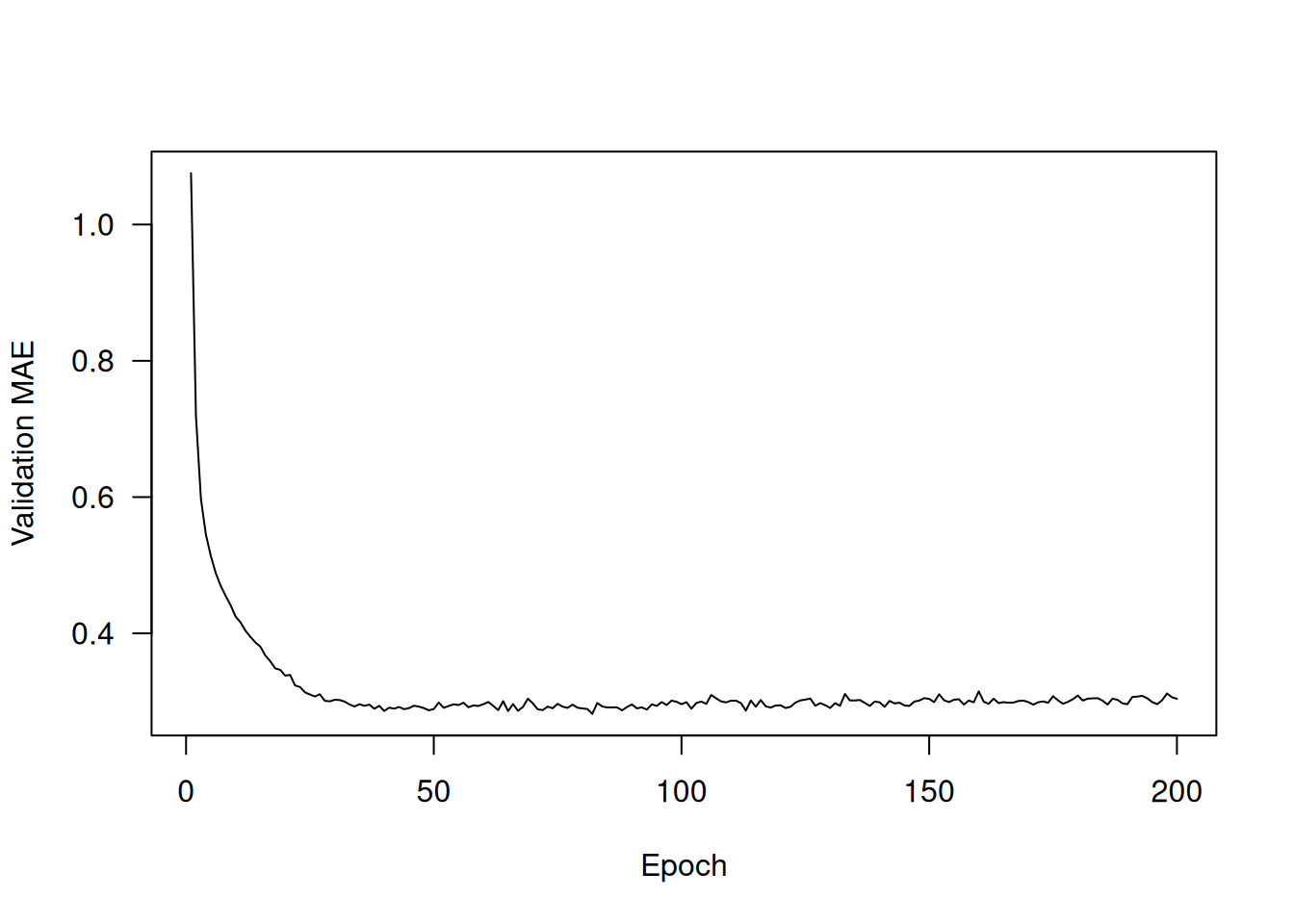

average_mae_history <- rowMeans(all_mae_histories)Let’s plot this; see figure 4.9.

plot(average_mae_history, ylab = "Validation MAE", xlab = "Epoch", type = 'l')It may be a little difficult to read the plot due to a scaling problem: the validation MAE for the first few epochs is dramatically higher than the values that follow. Let’s omit the first 10 data points, which are on a different scale than the rest of the curve (see figure 4.10).

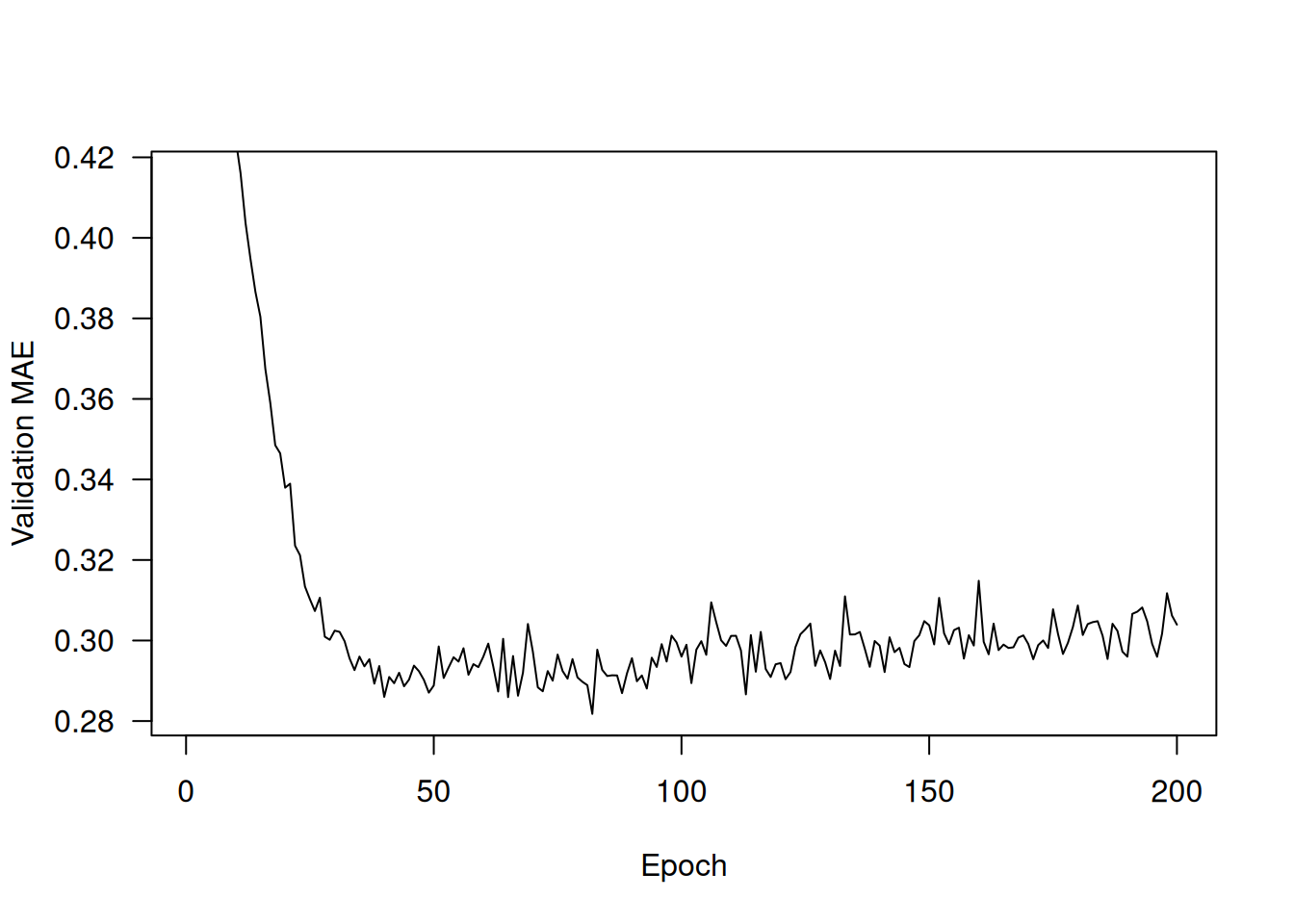

truncated_mae_history <- average_mae_history[-(1:10)]

plot(average_mae_history, type = 'l',

ylab = "Validation MAE", xlab = "Epoch",

ylim = range(truncated_mae_history))According to this plot, validation MAE stops improving significantly after 120–140 epochs (this number includes the 10 epochs we omitted). Past that point, we start overfitting.

Once we’re finished tuning other parameters of the model (in addition to the number of epochs, we could also adjust the size of the intermediate layers), we can train a final production model on all of the training data, with the best parameters, and then look at its performance on the test data.

- 1

- Gets a fresh, compiled model

- 2

- Trains it on the entirety of the data

Here’s the final result:

test_mean_absolute_error[1] 0.3312956We’re still off by about $33,000 on average.

4.3.5 Generating predictions on new data

When calling predict() on our binary classification model, we retrieved a scalar score between 0 and 1 for each input sample. With our multiclass classification model, we retrieved a probability distribution over all classes for each sample. Now, with this scalar regression model, predict() returns the model’s guess for the sample’s price in hundreds of thousands of dollars:

predictions <- model |> predict(x_test)

predictions[1, ][1] 2.452243The first district in the test set is predicted to have an average home price of about $245,000.

4.3.6 Wrapping up

Here’s what you should take away from this scalar regression example:

Regression is done using a different loss function than what we used for classification. Mean squared error (MSE) is a loss function commonly used for regression.

Similarly, evaluation metrics to be used for regression differ from those used for classification; naturally, the concept of accuracy doesn’t apply for regression. A common regression metric is mean absolute error (MAE).

When features in the input data have values in different ranges, each feature should be scaled independently as a preprocessing step.

When there is little data available, using K-fold validation is a great way to reliably evaluate a model.

When little training data is available, it’s preferable to use a small model with few intermediate layers (typically only one or two), to avoid severe overfitting.

4.4 Summary

The three most common kinds of machine learning tasks on vector data are binary classification, multiclass classification, and scalar regression. Each task uses different loss functions:

binary_crossentropyfor binary classificationcategorical_crossentropyfor multiclass classificationmean_squared_errorfor scalar regression

You’ll usually need to preprocess raw data before feeding it into a neural network.

When your data has features with different ranges, scale each feature independently as part of preprocessing.

As training progresses, neural networks eventually begin to overfit and obtain worse results on never-before-seen data.

If you don’t have much training data, use a small model with only one or two intermediate layers, to avoid severe overfitting.

If your data is divided into many categories, you may cause information bottlenecks if you make the intermediate layers too small.

When you’re working with little data, K-fold validation can help reliably evaluate your model.