library(fs)

data_dir <- path("pets_dataset")

dir_create(data_dir)11 Image segmentation

This chapter covers

- The branches of computer vision: image classification, image segmentation, and object detection

- Building a segmentation model from scratch

- Using the pretrained Segment Anything model

In chapter 8, you got a first introduction to deep learning for computer vision via a simple use case: binary image classification. But there’s more to computer vision than image classification! This chapter dives deeper into another essential computer vision application: image segmentation.

11.1 Computer vision tasks

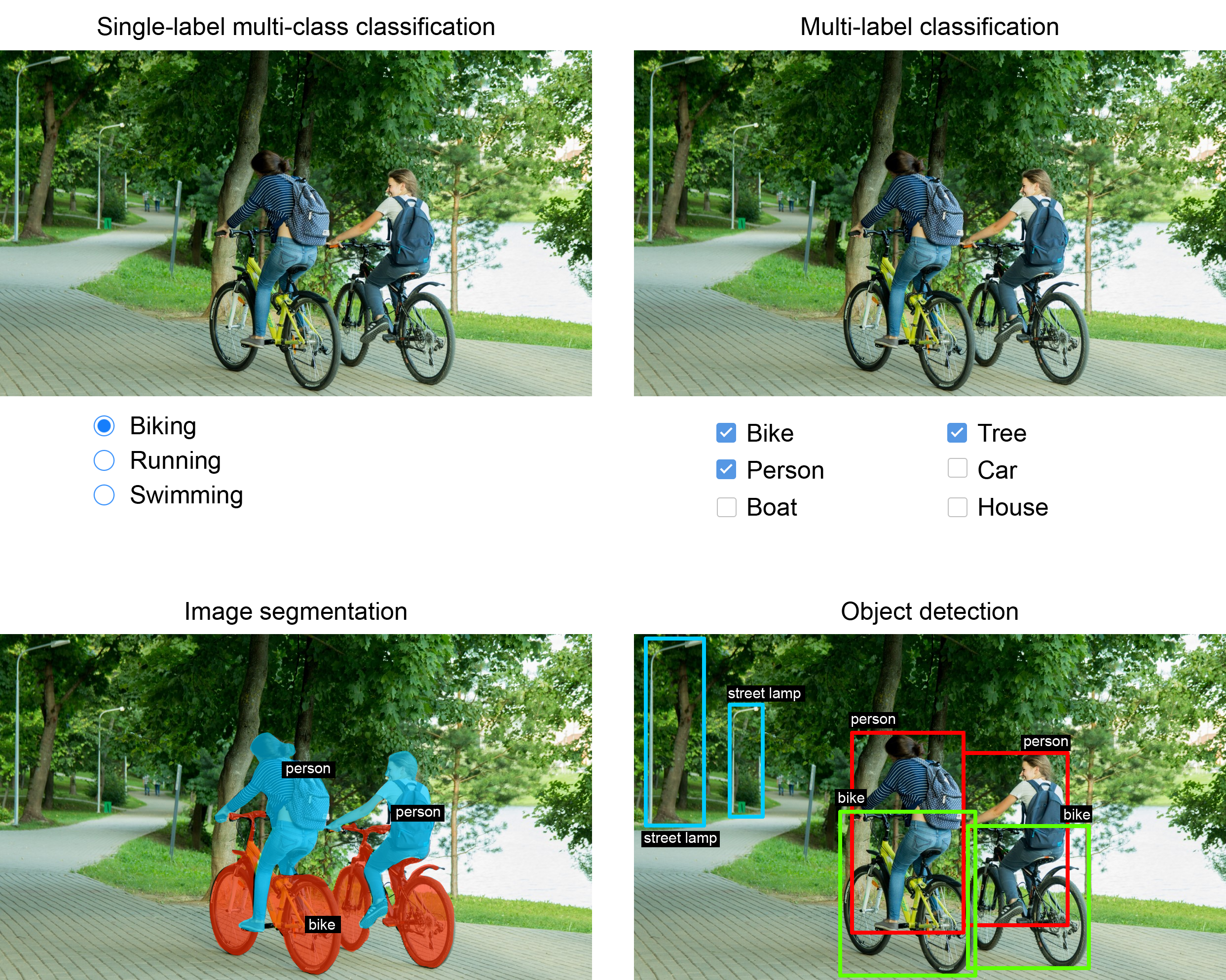

So far, we’ve focused on image classification models: an image goes in, a label comes out. “This image likely contains a cat; this other one likely contains a dog.” But image classification is only one of several possible applications of deep learning in computer vision. In general, there are three essential computer vision tasks you need to know about:

- Image classification—The goal is to assign one or more labels to an image. It may be either single-label classification (meaning categories are mutually exclusive) or multi-label classification (tagging all categories that an image belongs to, as seen in figure 11.1). For example, when we search for a keyword on the Google Photos app, behind the scenes we’re querying a very large multilabel classification model—one with more than 20,000 different classes, trained on millions of images.

- Image segmentation—The goal is to “segment” or “partition” an image into different areas, with each area usually representing a category (as seen in figure 11.1). For instance, when Zoom or Google Meet displays a custom background behind us in a video call, it’s using an image segmentation model to tell apart our face and what’s behind it, with pixel-level precision.

- Object detection—The goal is to draw rectangles (called bounding boxes) around objects of interest in an image and associate each rectangle with a class. A self-driving car could use an object detection model to monitor cars, pedestrians, and signs in view of its cameras, for instance.

Deep learning for computer vision also encompasses a number of somewhat more niche tasks besides these three, such as image similarity scoring (estimating how visually similar two images are), keypoint detection (pinpointing attributes of interest in an image, such as facial features), pose estimation, 3D mesh estimation, depth estimation, and so on. But to start with, image classification, image segmentation, and object detection form the foundation that every machine learning engineer should be familiar with. Almost all computer vision applications boil down to one of these three.

You saw image classification in action in the previous chapter. Next, let’s dive into image segmentation. It’s a very useful and very versatile technique, and you can straightforwardly approach it with what you’ve already learned so far. Then, in chapter 12, you’ll learn about object detection in detail.

11.1.1 Types of image segmentation

Image segmentation with deep learning is about using a model to assign a class to each pixel in an image, thus segmenting the image into different zones (such as “background” and “foreground” or “road,” “car,” and “sidewalk”). This general category of techniques can be used to power a considerable variety of valuable applications in image and video editing, autonomous driving, robotics, medical imaging, and so on.

You should know about these three flavors of image segmentation:

- Semantic segmentation—Each pixel is independently classified into a semantic category, like “cat.” If there are two cats in the image, the corresponding pixels are all mapped to the same generic “cat” category (see figure 11.2).

- Instance segmentation—Parses out individual object instances. In an image with two cats, instance segmentation will distinguish between pixels belonging to “cat 1” and pixels belonging to “cat 2” (see figure 11.2).

- Panoptic segmentation—Combines semantic segmentation and instance segmentation by assigning to each pixel in an image both a semantic label (like “cat”) and an instance label (like “cat 2”). This is the most informative of all three segmentation types.

To become more familiar with segmentation, let’s get started with training a small segmentation model from scratch.

11.2 Training a segmentation model from scratch

In this first example, we’ll focus on semantic segmentation. We’ll look once again at images of cats and dogs, and this time we’ll learn to tell apart the main subject and its background.

11.2.1 Downloading a segmentation dataset

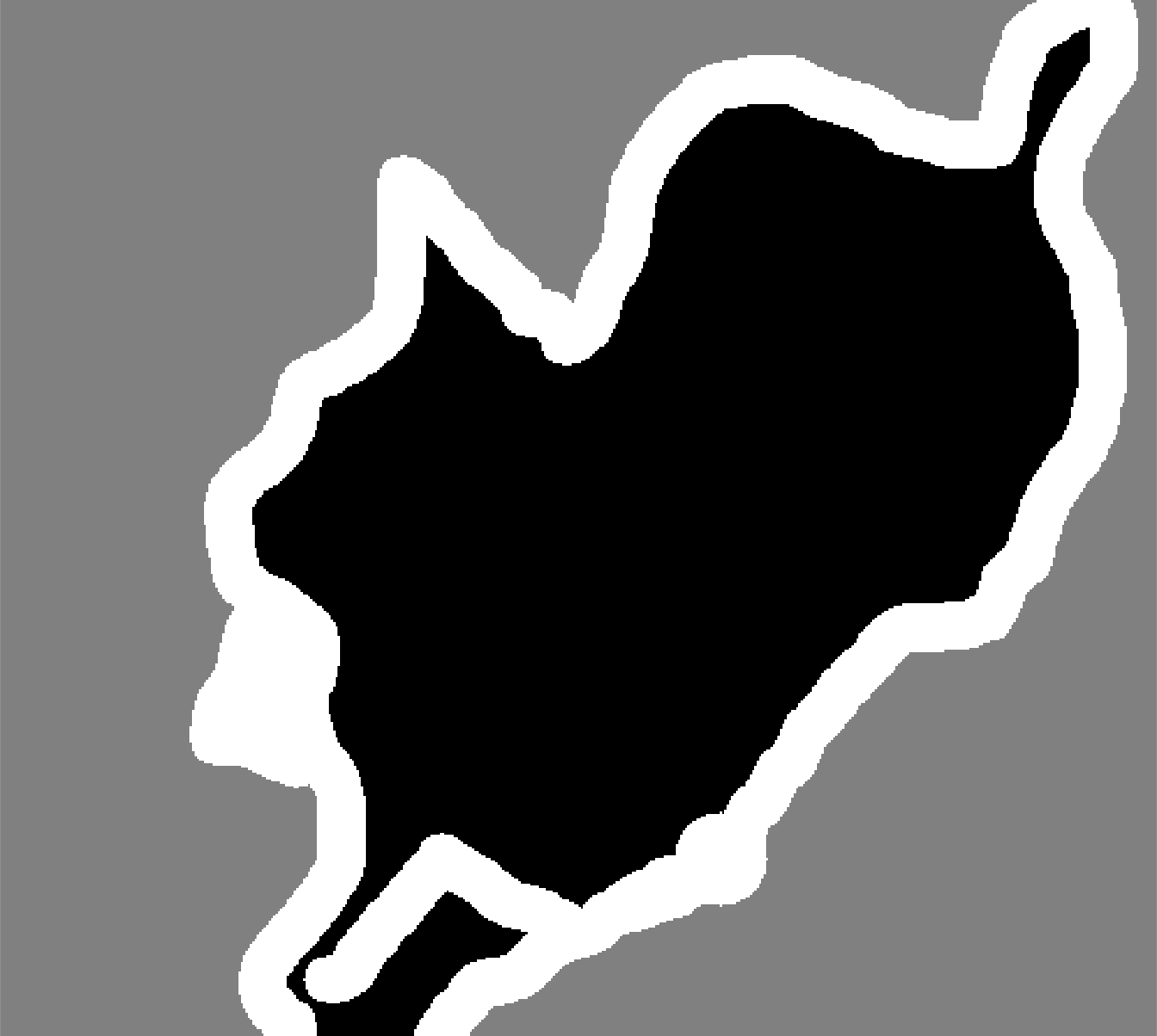

We’ll work with the Oxford-IIIT Pets dataset (https://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/data/pets/), which contains 7,390 pictures of various breeds of cats and dogs, together with foreground-background segmentation masks for each picture. A segmentation mask is the image-segmentation equivalent of a label: it’s an image the same size as the input image, with a single color channel in which each integer value corresponds to the class of the corresponding pixel in the input image. In our case, the pixels of our segmentation masks can take one of three integer values:

- 1 (foreground)

- 2 (background)

- 3 (contour)

Let’s start by downloading and uncompressing our dataset, using the download.file() and untar() functions provided by R. Just as in chapter 8, we’ll use the fs package for filesystem operations:

data_url <- path("http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/data/pets/data")

options(timeout = 3600)

for (filename in c("images.tar.gz", "annotations.tar.gz")) {

download.file(url = data_url / filename,

destfile = data_dir / filename)

untar(data_dir / filename, exdir = data_dir)

}The input pictures are stored as JPG files in the images/ folder (such as images/Abyssinian_1.jpg), and the corresponding segmentation mask is stored as a PNG file with the same name in the annotations/trimaps/ folder (such as annotations/trimaps/Abyssinian_1.png).

Let’s prepare a data frame with the input file paths and the corresponding mask file paths:

library(dplyr, warn.conflicts = FALSE)

input_dir <- data_dir / "images"

target_dir <- data_dir / "annotations/trimaps/"

all_image_paths <- tibble(

input = sort(dir_ls(input_dir, glob = "*.jpg")),

1 target = sort(dir_ls(target_dir, glob = "*.png", all = FALSE))

)- 1

-

Ignores spurious files in the trimaps directory that start with a

.

Now, what does one of these inputs and its mask look like? Let’s take a quick look; figure 11.3 shows the input image.

display_image <- function(x, ..., max = 255L, margin = 0) {

par(mar = rep(margin, 4))

x |> as.array() |> drop() |>

as.raster(max = max) |>

plot(..., interpolate = FALSE)

}In the as.raster() call, we set max = 255 because, just as with MNIST, the images are encoded as uint8. Unsigned 8-bit integers can encode values only in the range of [0, 255]:

1all_image_paths$input[10] |>

image_load() |> image_to_array() |>

display_image()- 1

- Displays input image number 10

Let’s look at the image’s target mask as well (see figure 11.4):

- 1

- The original labels are 1, 2, and 3. We subtract 1 so that the labels range from 0 to 2

- 2

-

We use

color_mode='grayscale'so that the image we load is treated as having a single color channel.

Next, we’ll split the image paths into training and validation sets, and then we’ll load our inputs and targets using tfdatasets.

library(tfdatasets, exclude = "shape")

img_size <- shape(200, 200)

tf_image_load <- function(path, target_size = NULL, ...) {

img <- path |>

tf$io$read_file() |>

tf$io$decode_image(..., expand_animations = FALSE)

if (!is.null(target_size))

img <- img |> tf$image$resize(target_size)

img

}

make_dataset <- function(image_paths) {

stopifnot(is.data.frame(image_paths),

names(image_paths) == c("input", "target"))

tensor_slices_dataset(image_paths) |>

dataset_map(function(example_paths) {

input_image <- example_paths$input |>

1 tf_image_load(channels = 3L, target_size = img_size)

target <- example_paths$target |>

2 tf_image_load(channels = 1L, target_size = img_size)

3 target <- tf$cast(target, "uint8") - 1L

list(input_image, target)

}) |>

4 dataset_cache() |>

5 dataset_shuffle(buffer_size = nrow(image_paths)) |>

dataset_batch(32)

}

6num_val_samples <- 1000

image_paths <- all_image_paths |>

dplyr::mutate(

7 use = ifelse(sample.int(n()) > num_val_samples, "train", "val")

) |>

tidyr::nest(.by = use) |>

tibble::deframe()

8train_ds <- make_dataset(image_paths$train)

val_ds <- make_dataset(image_paths$val)- 1

- Each input image is loaded with 3 channels: red, green, and blue.

- 2

- Each target image is loaded with a single channel representing pixel labels.

- 3

- Subtracts 1 so the pixel labels become 0, 1, and 2

- 4

- Caches the dataset in memory to speed up training. Remove if memory is limited.

- 5

- Shuffles the file paths after caching to randomize sample order each epoch

- 6

- Number of samples to hold out for validation

- 7

- Randomly assigns each sample to the training or validation set

- 8

- Creates datasets for training and validation

dataset_map()

dataset_map() calls our function with a symbolic TensorFlow tensor, which makes interactive exploration in the REPL a bit tricky. So how can we try things with the example_paths argument in Listing 11.2?

There are two approaches: eager tensors and symbolic tensors. To get an eager tensor, we pull a concrete example from the dataset:

example_paths <- tensor_slices_dataset(image_paths) |>

as_iterator() |> iter_next()We can now interact with example_paths at the REPL while writing and testing our function for dataset_map(). Just keep in mind that this is one specific example of a dataset element. In some datasets, elements may differ in shape, type, or structure: for instance, varying image sizes or batch dimensions.

In the actual pipeline, our function will be called in graph mode with symbolic tensors (the default mode in TensorFlow before v2). To inspect symbolic tensors interactively, use browser():

tensor_slices_dataset(image_paths$train) |>

dataset_map(function(example_paths) {

print(example_paths)

browser()

})The print() call will be evaluated only on the tracing tensor in R, typically only once when the function is first compiled—it will not be part of the TF graph. (To add a print() to the graph, use tf$print().)

The browser() pauses execution so we can inspect example_paths or the output of any tensor-returning function mid-trace, in that dataset_map() context. We can even write and test our function line by line inside the browser.

Important: don’t exit the browser() by pressing Esc or Q. Doing so can leave TensorFlow’s tracing context open, which will block eager execution and may even cause a segfault. Always continue (press C) and let errors propagate to safely close the context.

Let’s preview the first batch to confirm that the data looks correct:

batch <- train_ds |> as_iterator() |> iter_next()

str(batch)List of 2

$ :<tf.Tensor: shape=(32, 200, 200, 3), dtype=float32, numpy=…>

$ :<tf.Tensor: shape=(32, 200, 200, 1), dtype=uint8, numpy=…>.[images, targets] <- batch

par(mfrow = c(4, 8))

for (i in 1:16) {

images@r[i] |> display_image()

1 targets@r[i] |> display_target(offset = FALSE)

}- 1

- We already offset the labels in the dataset.

This should display a grid of input images and their corresponding masks (see figure 11.5).

11.2.2 Building and training the segmentation model

Now it’s time to define our model:

get_model <- function(img_size, num_classes) {

1 conv <- function(..., padding = "same", activation = "relu")

layer_conv_2d(..., padding = padding, activation = activation)

conv_transpose <- function(..., padding = "same", activation = "relu")

layer_conv_2d_transpose(..., padding = padding, activation = activation)

input <- keras_input(shape = c(img_size, 3))

output <- input |>

2 layer_rescaling(scale = 1/255) |>

conv(64, 3, strides = 2) |>

conv(64, 3) |>

conv(128, 3, strides = 2) |>

conv(128, 3) |>

conv(256, 3, strides = 2) |>

conv(256, 3) |>

conv_transpose(256, 3) |>

conv_transpose(256, 3, strides = 2) |>

conv_transpose(128, 3) |>

conv_transpose(128, 3, strides = 2) |>

conv_transpose(64, 3) |>

conv_transpose(64, 3, strides = 2) |>

3 conv(num_classes, 3, activation = "softmax")

keras_model(input, output)

}

model <- get_model(img_size = img_size, num_classes = 3)

model- 1

-

Defines local functions

conv()andconv_transpose()so we can avoid passing the same arguments to each call:padding = "same", activation = "relu". We usepadding = "same"everywhere to avoid the influence of border padding on feature map size. - 2

- Don’t forget to rescale input images to the [0-1] range.

- 3

- Ends the model with a per-pixel three-way softmax to classify each output pixel into one of our 3 categories.

Model: "functional"

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Layer (type) ┃ Output Shape ┃ Param # ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩

│ input_layer (InputLayer) │ (None, 200, 200, 3) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ rescaling (Rescaling) │ (None, 200, 200, 3) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d (Conv2D) │ (None, 100, 100, 64) │ 1,792 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_1 (Conv2D) │ (None, 100, 100, 64) │ 36,928 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_2 (Conv2D) │ (None, 50, 50, 128) │ 73,856 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_3 (Conv2D) │ (None, 50, 50, 128) │ 147,584 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_4 (Conv2D) │ (None, 25, 25, 256) │ 295,168 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_5 (Conv2D) │ (None, 25, 25, 256) │ 590,080 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_transpose │ (None, 25, 25, 256) │ 590,080 │

│ (Conv2DTranspose) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_transpose_1 │ (None, 50, 50, 256) │ 590,080 │

│ (Conv2DTranspose) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_transpose_2 │ (None, 50, 50, 128) │ 295,040 │

│ (Conv2DTranspose) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_transpose_3 │ (None, 100, 100, 128) │ 147,584 │

│ (Conv2DTranspose) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_transpose_4 │ (None, 100, 100, 64) │ 73,792 │

│ (Conv2DTranspose) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_transpose_5 │ (None, 200, 200, 64) │ 36,928 │

│ (Conv2DTranspose) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_6 (Conv2D) │ (None, 200, 200, 3) │ 1,731 │

└─────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────────┴───────────────┘

Total params: 2,880,643 (10.99 MB)

Trainable params: 2,880,643 (10.99 MB)

Non-trainable params: 0 (0.00 B)

The first half of the model closely resembles the kind of convnet we’d use for image classification: a stack of Conv2D layers, with gradually increasing filter sizes. We downsample our images three times by a factor of two each, ending up with activations of size (25, 25, 256). The purpose of this first half is to encode the images into smaller feature maps, where each spatial location (or “pixel”) contains information about a large spatial chunk of the original image. You can understand it as a kind of compression.

One important difference between the first half of this model and the classification models you’ve seen before is the way we do downsampling: in the classification convnets from the last chapter, we used MaxPooling2D layers to downsample feature maps. Here, we downsample by adding strides to every other convolution layer (if you don’t remember the details of how convolution strides work, see section 8.1.1). We do this because in the case of image segmentation, we care a lot about the spatial location of information in the image: we need to produce per-pixel target masks as output of the model. When we do 2 × 2 max pooling, we destroy location information within each pooling window: we return one scalar value per window, with zero knowledge of which of the four locations in the windows the value came from.

So, although max pooling layers perform well for classification tasks, they would hurt us for a segmentation task. Meanwhile, strided convolutions do a better job of downsampling feature maps while retaining location information. Throughout this book, you’ll notice that we tend to use strides instead of max pooling in any model that cares about feature location, such as the generative models in chapter 17.

The second half of the model is a stack of Conv2DTranspose layers. What are those? Well, the output of the first half of the model is a feature map of shape (25, 25, 256), but we want our final output to predict a class for each pixel, matching the original spatial dimensions. The final model output will have shape (200, 200, num_classes), which is (200, 200, 3) here. Therefore, we need to apply a kind of inverse of the transformations we’ve applied so far, something that will upsample the feature maps instead of downsampling them. That’s the purpose of the Conv2DTranspose layer: you can think of it as a kind of convolution layer that learns to upsample. If we have an input of shape (100, 100, 64) and we run it through the layer layer_conv_2d(128, 3, strides = 2, padding = "same"), we get an output of shape (50, 50, 128). If we run this output through the layer layer_conv_2d_transpose(64, 3, strides = 2, padding = "same"), we get back an output of shape (100, 100, 64), the same as the original. So after compressing our inputs into feature maps of shape (25, 25, 256) via a stack of Conv2D layers, we can simply apply the corresponding sequence of Conv2DTranspose layers followed by a final Conv2D layer to produce outputs of shape (200, 200, 3).

To evaluate the model, we’ll use a metric named Intersection over Union (IoU). It’s a measure of the match between the ground-truth segmentation masks and the predicted masks. It can be computed separately for each class or averaged over multiple classes. Here’s how it works:

- Compute the intersection between the masks: the area where the prediction and ground truth overlap.

- Compute the union of the masks: the total area covered by both masks combined. This is the whole space we’re interested in—the target object and any extra bits our model might have included by mistake.

- Divide the intersection area by the union area to get the IoU. It’s a number between 0 and 1, where 1 denotes a perfect match and 0 denotes a complete miss.

We can simply use a built-in Keras metric rather than building this ourselves:

- 1

- Specifies the total number of classes

- 2

- Specifies the class to compute IoU for (0 = foreground)

- 3

- Our targets are sparse (integer class IDs).

- 4

- But our model’s predictions are a dense softmax!

We can now compile and fit our model:

model |> compile(

optimizer = "adam",

loss = "sparse_categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = foreground_iou

)

callbacks <- list(

callback_model_checkpoint("oxford_segmentation.keras", save_best_only = TRUE)

)history <- model |> fit(

train_ds,

epochs = 50,

callbacks = callbacks,

validation_data = val_ds

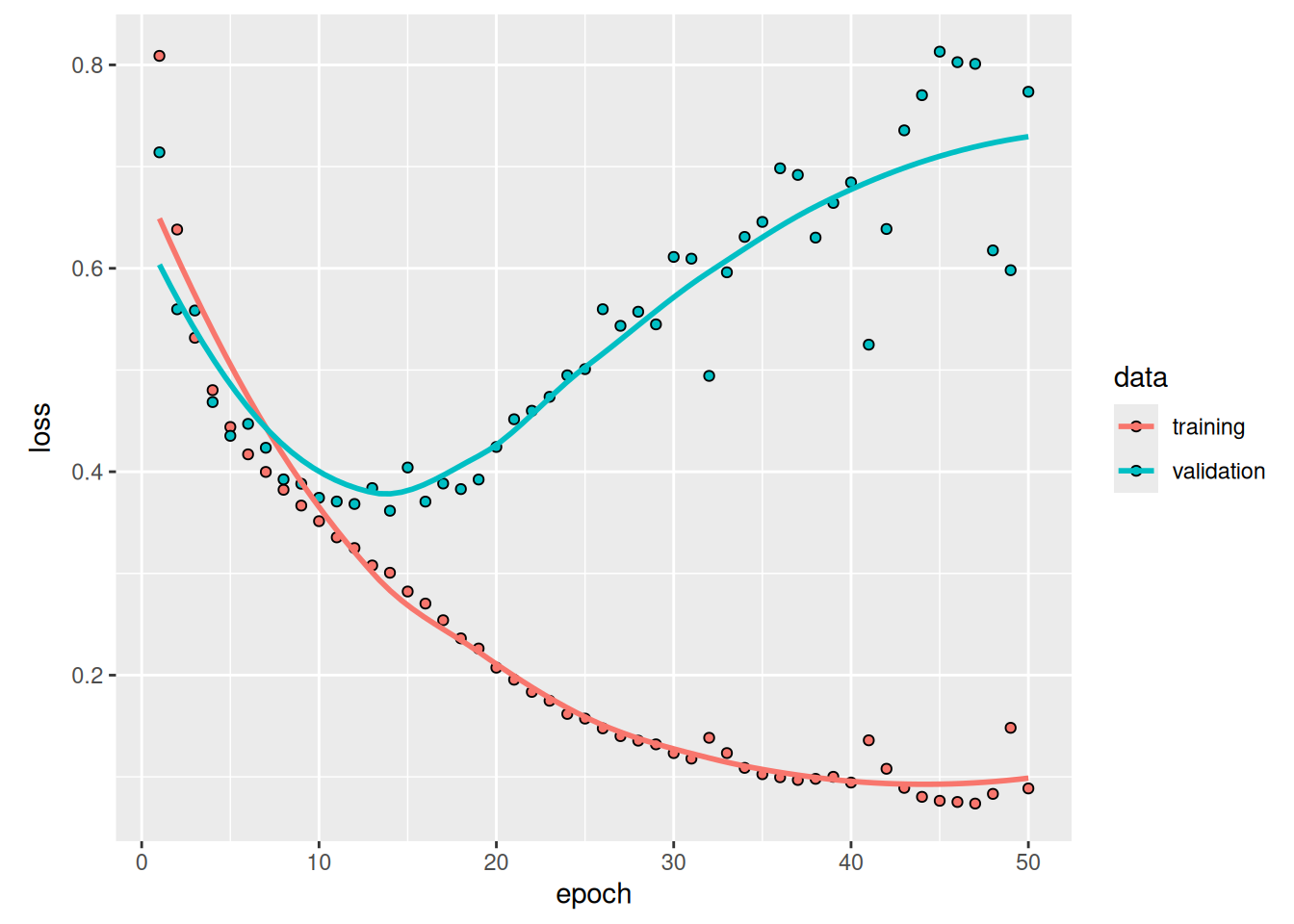

)Let’s display our training and validation loss (see figure 11.6):

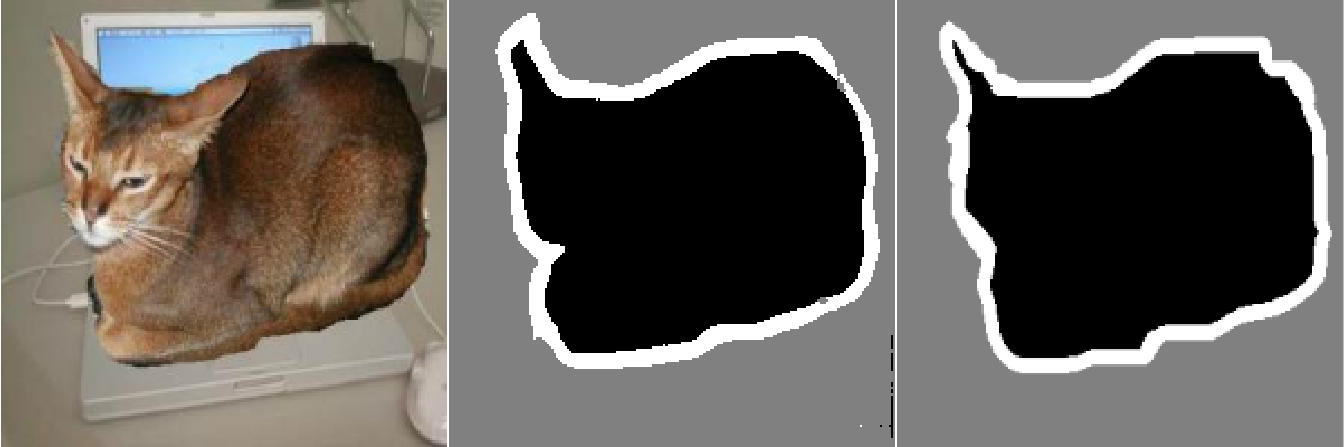

You can see that we start overfitting early, before epoch 25. Let’s reload our best-performing model according to validation loss and demonstrate how to use it to predict a segmentation mask (see figure 11.7):

model <- load_model("oxford_segmentation.keras")i <- 12

test_image <- image_paths$val$input[i] |>

tf_image_load(channels = 3L, target_size = img_size)

test_mask <- image_paths$val$target[i] |>

tf_image_load(channels = 1L, target_size = img_size) |>

tf$subtract(1)

predicted_mask_probs <- model(test_image@r[newaxis])

predicted_mask <- op_argmax(predicted_mask_probs, axis = -1,

1 zero_indexed = TRUE)

par(mfrow = c(1, 3))

display_image(test_image)

display_target(predicted_mask, offset = FALSE)

display_target(test_mask, offset = FALSE)- 1

-

Sets

zero_indexed=TRUEto return already-offset labels in [0, 1, 2]

There are a couple of small artifacts in our predicted mask, caused by geometric shapes in the foreground and background. Nevertheless, our model appears to work nicely.

11.3 Using a pretrained segmentation model

In the image classification example from chapter 8, you saw how using a pretrained model can significantly boost our accuracy—especially when we have only a few samples to train on. Image segmentation is no different.

The Segment Anything model (SAM; Kirillov et al., “Segment Anything,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, arXiv (2023), https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.02643) is a powerful pretrained segmentation model we can use for, well, almost anything. It was developed by Meta AI and released in April 2023. It was trained on 11 million images and their segmentation masks, covering more than 1 billion object instances. This massive amount of training data provides the model with built-in knowledge of virtually any object that appears in natural images.

The main innovation of SAM is that it’s not limited to a predefined set of object classes. We can use it for segmenting new objects simply by providing an example of what we’re looking for. We don’t even need to fine-tune the model first. Let’s see how that works.

11.3.1 Downloading the Segment Anything Model

First, let’s instantiate SAM and download its weights. Once again, we can use the KerasHub package to use this pretrained model without needing to implement it ourselves from scratch.

Remember the ImageClassifier task we used in the previous chapter? We can use another KerasHub task, ImageSegmenter, to wrap pretrained image segmentation models into a high-level model with standard inputs and outputs. Here, we’ll use the sam_huge_sa1b pretrained model, where sam stands for the model, huge refers to the number of parameters in the model, and sa1b stands for the SA-1B dataset released along with the model, with 1 billion annotated masks. Let’s download it now:

- 1

-

Informs reticulate that we need the Python package

keras-hub - 2

-

Now we can import the

keras_hubPython module.

One thing we can note off the bat is that our model is, indeed, huge:

count_params(model) |> prettyNum(",")[1] "641,090,864"At 641 million parameters, SAM is the largest model we have used so far in this book. The trend of pretrained models getting larger and larger and using more and more data will be discussed in more detail in chapter 16.

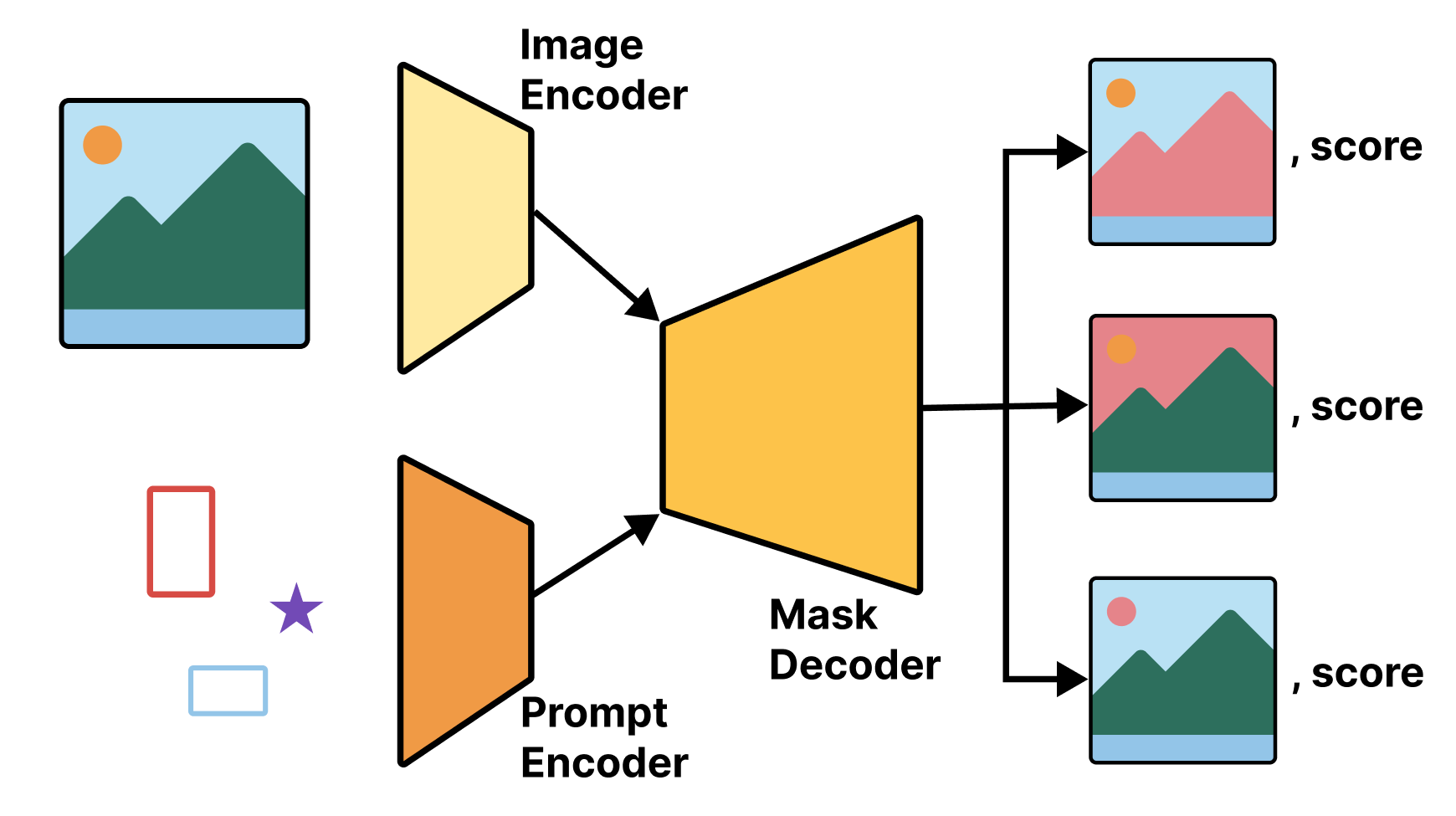

11.3.2 How Segment Anything works

Before we try running some segmentation with the model, let’s talk a little more about how the model works. Much of the model’s capability comes from the scale of the pretraining dataset. Meta developed the SA-1B dataset along with the model, and the partially trained model was used to assist with the data labeling process. That is, the dataset and model were developed together in a feedback loop of sorts.

The goal with the SA-1B dataset is to create fully segmented images, where every object in an image is given a unique segmentation mask; figure 11.8 shows an example. Each image in the dataset has an average of about 100 masks, and some images have more than 500 individually masked objects. This was done through a pipeline of increasingly automated data collection. At first, human experts manually segmented a small example dataset of images, which was used to train an initial model. This model was used to help drive a semiautomated stage of data collection, during which images were first segmented by SAM and then improved by human correction and further annotation.

The model is trained on (image, prompt, mask) triples. image and prompt are the model inputs. The image can be any input image, and the prompt can take a couple of forms:

- A point inside the object to mask

- A box around the object to mask

Given the image and prompt input, the model is expected to produce an accurate predicted mask for the object indicated by the prompt, which is compared with a ground truth mask label.

The model consists of a few separate components: an image encoder, similar to the Xception model we used in previous chapters, takes an input image and outputs a much smaller image embedding. This is something we already know how to build.

Next, we add a prompt encoder, which is responsible for mapping prompts in any of the previously mentioned forms to an embedded vector, and a mask decoder, which takes in both the image embedding and prompt embedding and outputs a few possible predicted masks. We won’t get into the details of the prompt encoder and mask decoder here, as they use some modeling techniques we won’t discuss until later chapters. We can compare these predicted masks with our ground truth mask, much as we did in the earlier section of this chapter (see figure 11.9).

All of these subcomponents are trained simultaneously by forming batches of new (image, prompt, mask) triples to train on from the SA-1B image and mask data. The process is actually quite simple. For a given input image, choose a random mask in the input. Next, randomly choose whether to create a box prompt or a point prompt. To create a point prompt, choose a random pixel inside the mask label. To create a box prompt, draw a box around all points inside the mask label. We can repeat this process indefinitely, sampling a number of (image, prompt, mask) from each image input.

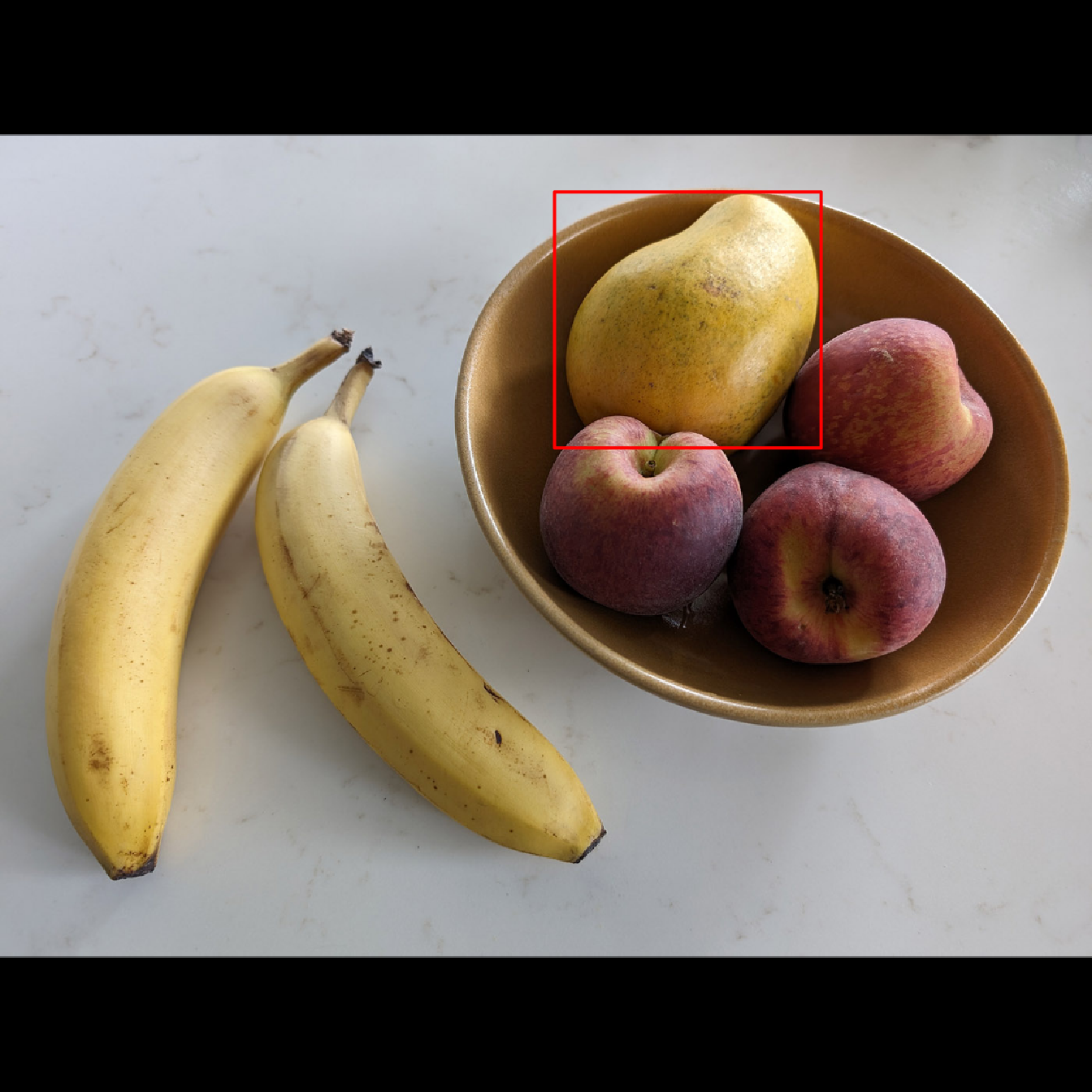

11.3.3 Preparing a test image

Let’s make this a little more concrete by trying the model. We can start by loading a test image for our segmentation work. We’ll use a picture of some fruit (see figure 11.10):

- 1

- Downloads the image and returns the local file path

- 2

- Loads the image as a Python Imaging Library (PIL) object

- 3

- Turns the PIL object into a NumPy matrix

<numpy.ndarray shape(1054,1400,3), dtype=float32>1display_image(image_array)- 1

- Displays the image NumPy array (defined in Listing 11.1)

SAM expects inputs that are 1,024 × 1,024. However, forcibly resizing arbitrary images to 1,024 × 1,024 would distort their aspect ratio—for instance, our image isn’t square. It’s better to first resize the image so that its longest side becomes 1,024 pixels long and then pad the remaining pixels with a filler value, such as 0. We can achieve this with the pad_to_aspect_ratio argument in the op_image_resize() operation, like this:

image_size <- c(1024, 1024)

resize_and_pad <- function(x) {

op_image_resize(x, image_size, pad_to_aspect_ratio = TRUE)

}

image <- resize_and_pad(image_array)

op_shape(image)shape(1024, 1024, 3)Next, let’s define a few utilities that will come in handy when using the model. We’re going to need to do the following:

- Display images.

- Display segmentation masks overlaid on an image.

- Highlight specific points on an image.

- Display boxes overlaid on an image.

The model works with screen coordinates, meaning that (0, 0) corresponds to the top-left corner of the image (a common convention in the computer graphics and image processing fields). R’s graphics device, however, uses Cartesian coordinates, where (0, 0) maps to the bottom-left corner. In the examples, we’ll work with screen coordinates and then convert them to Cartesian coordinates for plotting in our utility functions:

display_points <- function(coords, color = "white") {

stopifnot(is.matrix(coords), ncol(coords) == 2)

1 coords[, 2] <- image_size[1] - coords[, 2]

points(coords, col = color, pch = 8, cex = 2, lwd = 2)

}

display_mask <- function(mask, index = 1,

color = "dodgerblue", alpha = 0.6) {

.[r, g, b] <- col2rgb(color)

color <- rgb(r, g, b, alpha * 255, maxColorValue = 255)

mask <- mask |> as.array() |> drop() |> _[index, , ]

mask[] <- ifelse(mask > 0, color, rgb(0, 0, 0, 0))

.[h, w] <- image_size

rasterImage(mask, 0, 0, h, w, interpolate = FALSE)

}

display_box <- function(box, ..., color = "red", lwd = 2) {

stopifnot(is.matrix(box), dim(box) == c(2, 2))

2 box[, 2] <- image_size[1] - box[, 2]

rect(xleft = box[1, 1], ytop = box[1, 2],

xright = box[2, 1], ybottom = box[2, 2],

..., border = color, lwd = lwd)

}- 1

- Translates y axis values from screen to Cartesian coordinates

- 2

- Translates y-axis values from screen to Cartesian coordinates

11.3.4 Prompting the model with a target point

To use SAM, we need to prompt it. This means we need one of the following:

- Point prompts—Select a point in an image, and let the model segment the object that the point belongs to.

- Box prompts—Draw an approximate box around an object (it does not need to be particularly precise), and let the model segment the object in the box.

Let’s start with a point prompt. Points are labeled, with 1 indicating the foreground (the object we want to segment) and 0 indicating the background (everything around the object). In ambiguous cases, to improve our results, we can pass multiple labeled points, instead of a single point, to refine our definition of what should be included (points labeled 1) and what should be excluded (points labeled 0).

Let’s try a single foreground point (see figure 11.11). Here’s a test point:

- 1

- Coordinates of our point

- 2

- 1 means foreground, and 0 means background.

Let’s prompt SAM with it. First, we need to prepare our input data. We can inspect model$input to see what the model expects:

1str(model$input)- 1

-

Note that it’s

input, notinputs.

List of 5

$ images:<KerasTensor shape=(None, 1024, 1024, 3), dtype=float32, sparse=False, ragged=False, name=images>

$ points:<KerasTensor shape=(None, None, 2), dtype=float32, sparse=False, ragged=False, name=points>

$ labels:<KerasTensor shape=(None, None), dtype=float32, sparse=False, ragged=False, name=labels>

$ boxes :<KerasTensor shape=(None, None, 2, 2), dtype=float32, sparse=False, ragged=False, name=boxes>

$ masks :<KerasTensor shape=(None, None, None, None, 1), dtype=float32, sparse=False, ragged=False, name=masks>The model has five inputs. For this first example, we’ll use only three: images, points, and labels. These should have ranks 4, 3, and 2, respectively, and all are expected to be float32. We can prepare the inputs by casting them to float32 NumPy arrays and adding a batch dimension, like this:

- 1

-

convert=FALSEto prevent NumPy arrays from converting to R arrays - 2

- Adds a batch dimension; note that the axis argument is zero-based

<numpy.ndarray shape(1,1024,1024,3), dtype=float32>To work with NumPy arrays in R, we import the numpy module with convert=FALSE. The convert=FALSE argument stops reticulate from automatically converting NumPy arrays to R arrays. All functions and attributes we access from this np object will inherit the same convert value. To later convert the NumPy arrays to R arrays, we can call as.array() or py_to_r().

When using NumPy directly like this, keep in mind that, just as with TensorFlow, JAX, and PyTorch, the API uses zero-based indexing, and you will often have to append L to numbers to explicitly pass an integer literal. See chapter 2 for more about using NumPy in R.

Now let’s prompt the model:

outputs <- model |> predict(list(

images = image |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L),

points = input_point |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L),

labels = input_label |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L)

))The return value outputs has a masks field that contains four 256 × 256 candidate masks for the target object, ranked by decreasing match quality. The quality scores of the masks are available under the iou_pred field as part of the model’s output:

str(outputs)List of 2

$ iou_pred: num [1, 1:4] 0.981 1.01 0.917 0.852

$ masks : num [1, 1:4, 1:256, 1:256] -17.99 -26.68 -12.91 -7.15 -17.17 ...Let’s overlay the first mask on the image (see figure 11.12):

Pretty good! Next, let’s try a banana. We’ll prompt the model with coordinates (300, 550), which land on the second banana from the left (see figure 11.13):

input_label <- 1

input_point <- rbind(c(300, 550))

outputs <- model |> predict(list(

images = image |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L),

points = input_point |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L),

labels = input_label |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L)

))

display_image(image)

display_mask(outputs$masks)

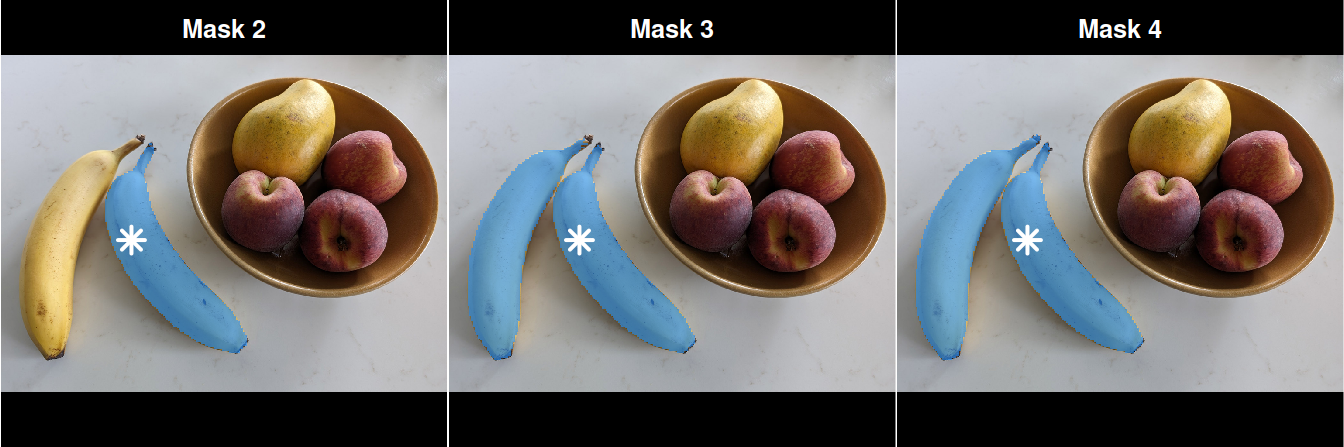

display_points(input_point)What about the other mask candidates? Those can come in handy for ambiguous prompts. Let’s try to plot the remaining three masks (see figure 11.14):

par(mfrow = c(1, 3))

for (i in 2:4) {

display_image(image)

display_mask(outputs$masks, index = i)

display_points(input_point)

title(paste("Mask", i), col.main= "white", line = -1.5)

}As you can see, an alternative segmentation found by the model includes both bananas.

11.3.5 Prompting the model with a target box

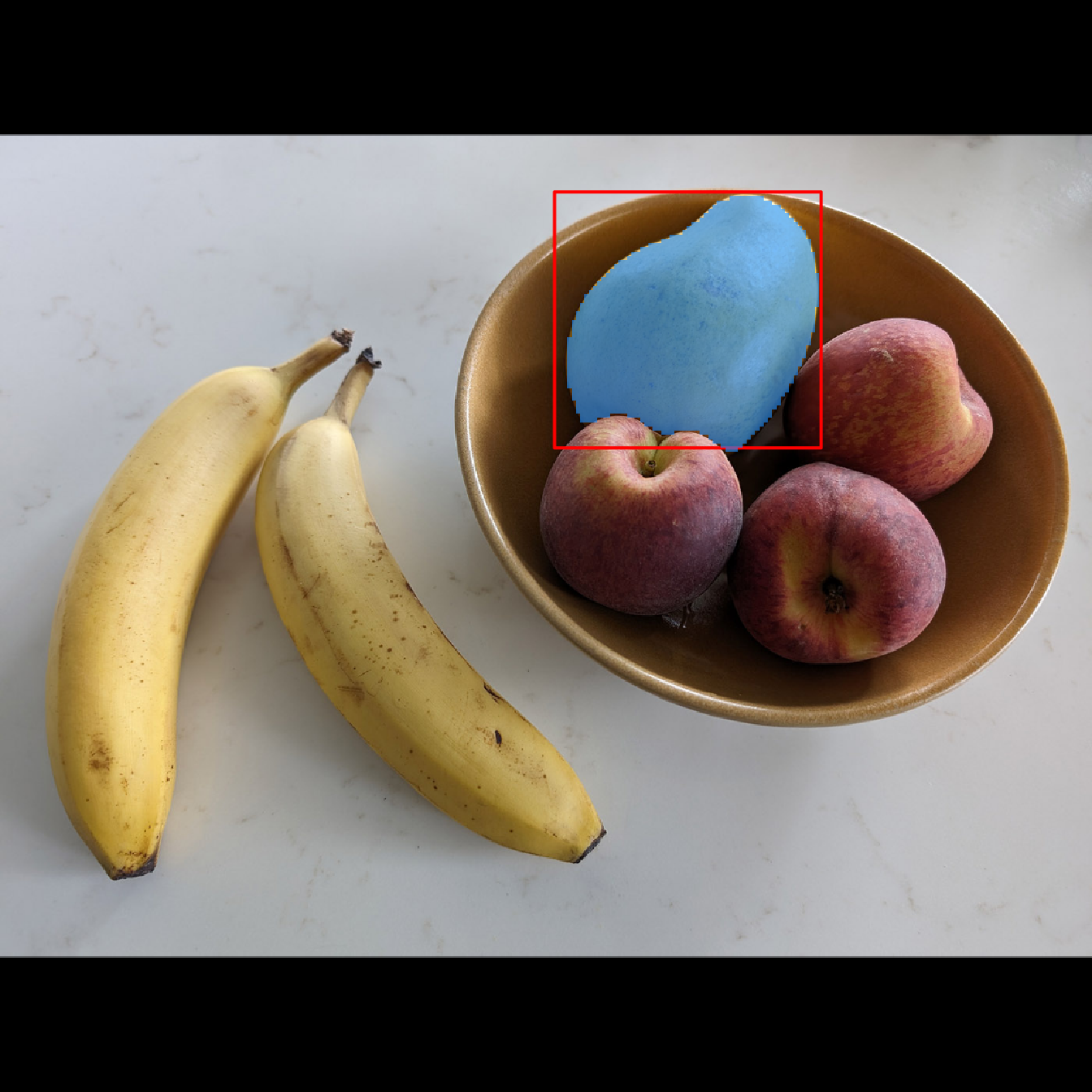

Besides providing one or more target points, we can provide boxes approximating the location of the object to segment. These boxes should be passed via the coordinates of their top-left and bottom-right corners. Here’s a box around the mango (see figure 11.15):

- 1

- Top-left corner

- 2

- Bottom-right corner

Let’s prompt SAM with it (see figure 11.16):

outputs <- model |> predict(list(

images = image |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(0L),

1 boxes = input_box |> np_array("float32") |> np$expand_dims(c(0L, 1L))

))

display_image(image)

display_box(input_box)

display_mask(outputs$masks)- 1

-

Note that we expand

boxesto a rank-4 array.

SAM can be a powerful tool to quickly create large datasets of images annotated with segmentation masks.

11.4 Summary

- Image segmentation is one of the main categories of computer vision tasks. It consists of computing segmentation masks that describe the contents of an image at the pixel level.

- To build your own segmentation model, use a stack of strided

Conv2Dlayers to “compress” the input image into a smaller feature map, followed by a stack of correspondingConv2DTransposelayers to “expand” the feature map into a segmentation mask the same size as the input image. - You can also use a pretrained segmentation model. Segment Anything, available via KerasHub, is a powerful model that supports point prompts and box prompts to guide segmentation.