library(keras3)

inputs <- keras_input(shape = c(28, 28, 1))

outputs <- inputs |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 64, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 128, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 256, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_global_average_pooling_2d() |>

layer_dense(10, activation = "softmax")

model <- keras_model(inputs = inputs, outputs = outputs)8 Image classification

This chapter covers

- Understanding convolutional neural networks (convnets)

- Using data augmentation to mitigate overfitting

- Using a pretrained convnet for feature extraction

- Fine-tuning a pretrained convnet

Computer vision was the first big success story of deep learning. It led to the initial rise of deep learning between 2011 and 2015. A type of deep learning called convolutional neural networks started getting remarkably good results on image classification competitions around that time, first with Dan Ciresan winning two niche competitions (the ICDAR 2011 Chinese character recognition competition and the IJCNN 2011 German traffic signs recognition competition) and then, more notably, in fall 2012, with Hinton’s group winning the high-profile ImageNet large-scale visual recognition challenge. Many more promising results quickly bubbled up in other computer vision tasks.

Interestingly, these early successes weren’t quite enough to make deep learning mainstream at the time—it took a few years. The computer vision research community had spent many years investing in methods other than neural networks, and it wasn’t ready to give up on them just because there was a new kid on the block. In 2013 and 2014, deep learning still faced intense skepticism from many senior computer vision researchers. Only in 2016 did it finally become dominant. One author remembers exhorting an ex-professor, in February 2014, to pivot to deep learning. “It’s the next big thing!” he would say. “Well, maybe it’s just a fad,” the professor would reply. By 2016, his entire lab was doing deep learning. There’s no stopping an idea whose time has come.

Today, you’re constantly interacting with deep learning-based vision models—via Google Photos, Google image search, the camera on your phone, YouTube, OCR software, and many more. These models are also at the heart of cutting-edge research in autonomous driving, robotics, AI-assisted medical diagnosis, autonomous retail checkout systems, and even autonomous farming.

This chapter introduces convolutional neural networks, also known as convnets or CNNs, the type of deep learning model that is used by most computer vision applications. You’ll learn to apply convnets to image classification problems—in particular, those involving small training datasets, which are the most common use case if you aren’t a large tech company.

8.1 Introduction to convnets

We’re about to dive into the theory of what convnets are and why they have been so successful at computer vision tasks. But first, let’s take a practical look at a simple convnet example. It uses a convnet to classify MNIST digits, a task we performed in chapter 2 using a densely connected network (our test accuracy then was 97.8%). Even though the convnet will be basic, its accuracy will blow that of the densely connected model from chapter 2 out of the water.

The following lines of code show what a basic convnet looks like. It’s a stack of Conv2D and MaxPooling2D layers. You’ll see in a minute exactly what they do. We’ll build the model using the Functional API, which we introduced in the previous chapter.

Importantly, a convnet takes as input tensors of shape (image_height, image_width, image_channels) (not including the batch dimension). In this case, we’ll configure the convnet to process inputs of size (28, 28, 1), which is the format of MNIST images.

Let’s display the architecture of our convnet.

modelModel: "functional"

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Layer (type) ┃ Output Shape ┃ Param # ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩

│ input_layer (InputLayer) │ (None, 28, 28, 1) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d (Conv2D) │ (None, 26, 26, 64) │ 640 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ max_pooling2d (MaxPooling2D) │ (None, 13, 13, 64) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_1 (Conv2D) │ (None, 11, 11, 128) │ 73,856 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ max_pooling2d_1 (MaxPooling2D) │ (None, 5, 5, 128) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_2 (Conv2D) │ (None, 3, 3, 256) │ 295,168 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ global_average_pooling2d │ (None, 256) │ 0 │

│ (GlobalAveragePooling2D) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ dense (Dense) │ (None, 10) │ 2,570 │

└─────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────────┴───────────────┘

Total params: 372,234 (1.42 MB)

Trainable params: 372,234 (1.42 MB)

Non-trainable params: 0 (0.00 B)

You can see that the output of every Conv2D and MaxPooling2D layer is a 3D tensor of shape (height, width, channels). The width and height dimensions tend to shrink as we go deeper in the model. The number of channels is controlled by the filters argument passed to layer_conv_2d() (64, 128, or 256).

Some deep learning libraries flip the location of channels in image tensors to the first rank (notably, much of the PyTorch ecosystem). Rather than passing images with shape (height, width, channels), we would pass (channels, height, width).

This is purely a matter of convention, and in Keras, it is configurable. We can call config_set_image_data_format("channels_first") to change Keras’s default, or pass a data_format argument to any conv or pooling layer. In general, you can leave the default as-is unless you have a specific need for "channels_first".

After the last Conv2D layer, we end up with an output of shape (3, 3, 256): a 3 × 3 feature map of 256 channels. The next step is to feed this output into a densely connected classifier like those you’re already familiar with: a stack of Dense layers. These classifiers process vectors, which are 1D, whereas the current output is a rank-3 tensor. To bridge the gap, we flatten the 3D outputs to 1D with a GlobalAveragePooling2D layer before adding the Dense layers. This layer will take the average of each 3 × 3 feature map in the tensor of shape (3, 3, 256), resulting in an output vector of shape (256). Finally, we’ll do 10-way classification so our last layer has 10 outputs and a softmax activation.

Now, let’s train the convnet on the MNIST digits. We’ll reuse a lot of the code from the MNIST example in chapter 2. Because we’re doing 10-way classification with a softmax output, we’ll use the categorical cross-entropy loss, and because our labels are integers, we’ll use the sparse version, sparse_categorical_crossentropy.

.[.[train_images, train_labels],

.[test_images, test_labels]] <- dataset_mnist()

1train_images <- array_reshape(train_images, c(-1, 28, 28, 1)) / 255

test_images <- array_reshape(test_images, c(-1, 28, 28, 1)) / 255

model |> compile(

optimizer = "rmsprop",

loss = "sparse_categorical_crossentropy",

metrics = c("accuracy")

)

model |> fit(train_images, train_labels, epochs = 5, batch_size = 64)- 1

- Reshapes to add a channels dim of size 1, divide by 255 to rescale from [0-255] to [0-1], and promote ints to floats in the process.

Let’s evaluate the model on the test data.

result <- evaluate(model, test_images, test_labels)

cat("Test accuracy:", result$accuracy, "\n")Test accuracy: 0.992 Whereas the densely connected model from chapter 2 had a test accuracy of 97.8%, the basic convnet has a test accuracy of 99.2%: we decreased the error rate by about 60% (relative). Not bad!

But why does this simple convnet work so well, compared to a densely connected model? To answer this, let’s dive into what the Conv2D and MaxPooling2D layers do.

8.1.1 The convolution operation

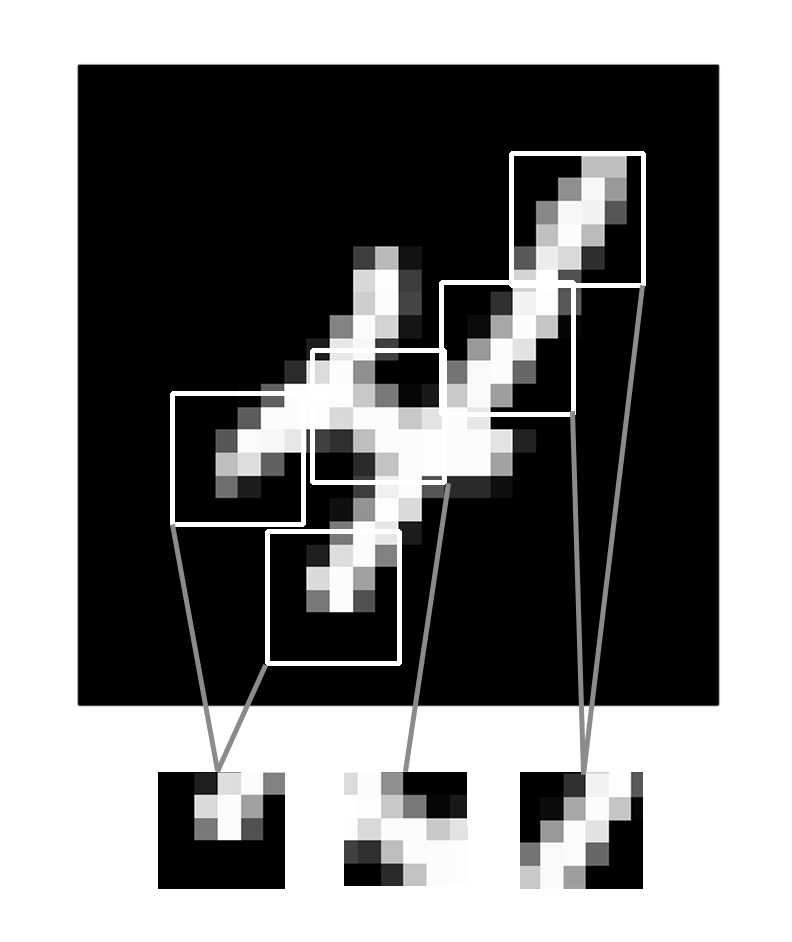

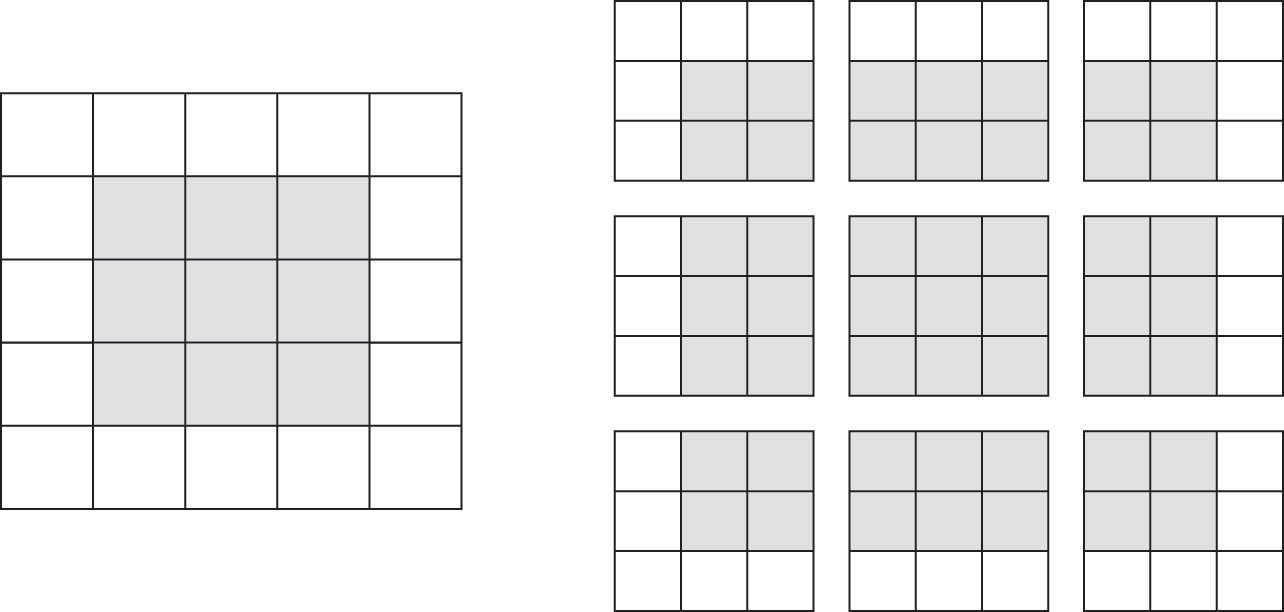

The fundamental difference between a densely connected layer and a convolution layer is this: Dense layers learn global patterns in their input feature space (for example, for a MNIST digit, patterns involving all pixels), whereas convolution layers learn local patterns (see figure 8.1): in the case of images, patterns found in small 2D windows of the inputs. In the previous example, these windows were all 3 × 3.

This key characteristic gives convnets two interesting properties:

The patterns they learn are translation invariant. After learning a certain pattern in the lower-right corner of a picture, a convnet can recognize it anywhere: for example, in the upper-left corner. A densely connected model would have to learn the pattern anew if it appeared at a new location. This makes convnets data efficient when processing images because the visual world is fundamentally translation invariant. They need fewer training samples to learn representations that have generalization power.

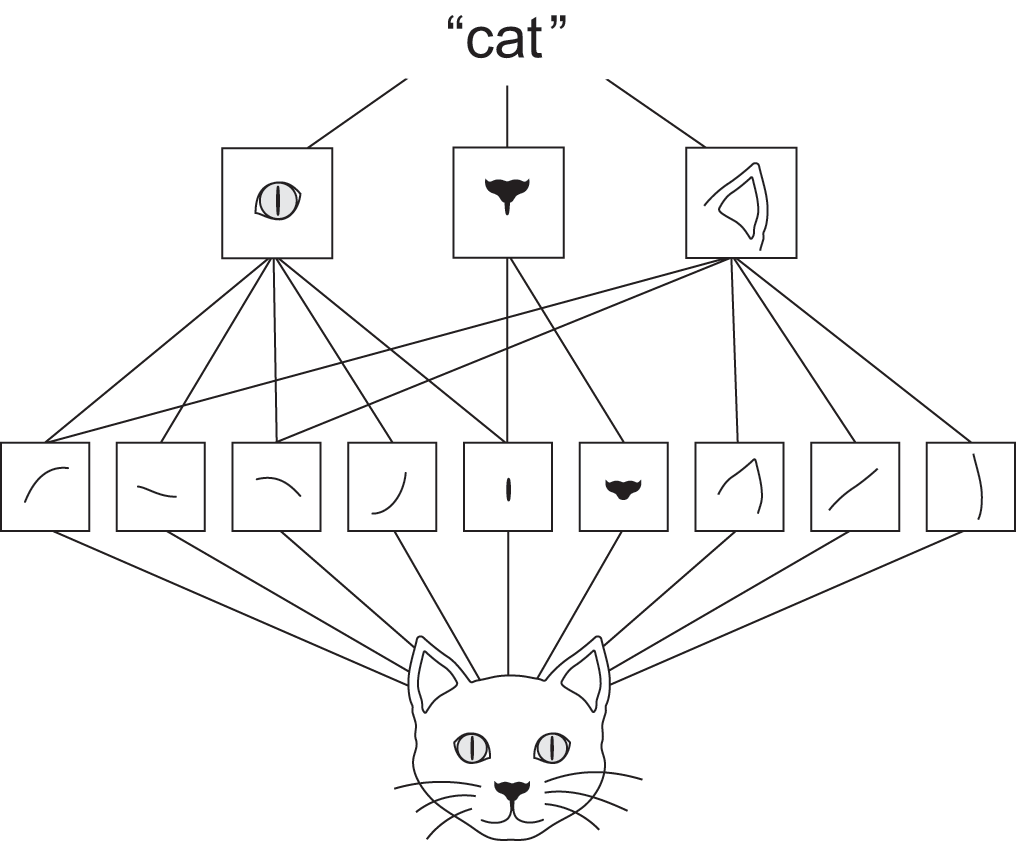

They can learn spatial hierarchies of patterns (see figure 8.2). A first convolution layer will learn small local patterns such as edges, a second convolution layer will learn larger patterns made of the features of the first layer, and so on. This allows convnets to efficiently learn increasingly complex and abstract visual concepts because the visual world is fundamentally spatially hierarchical.

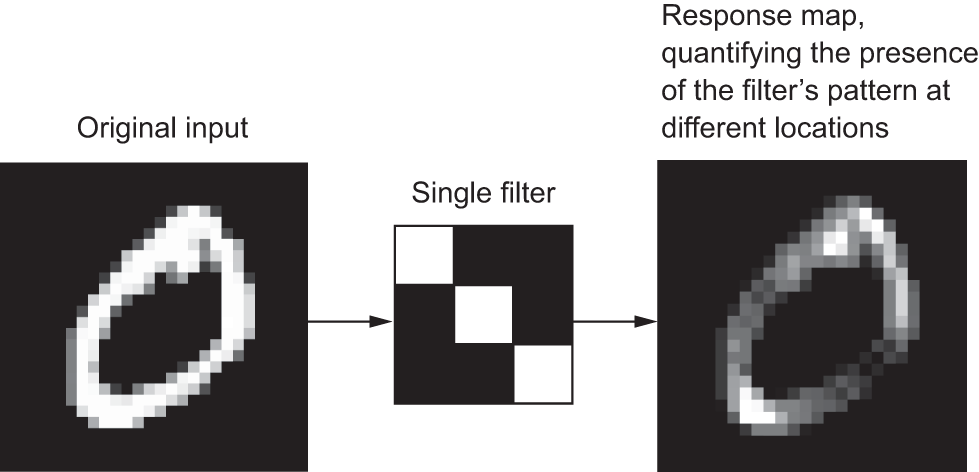

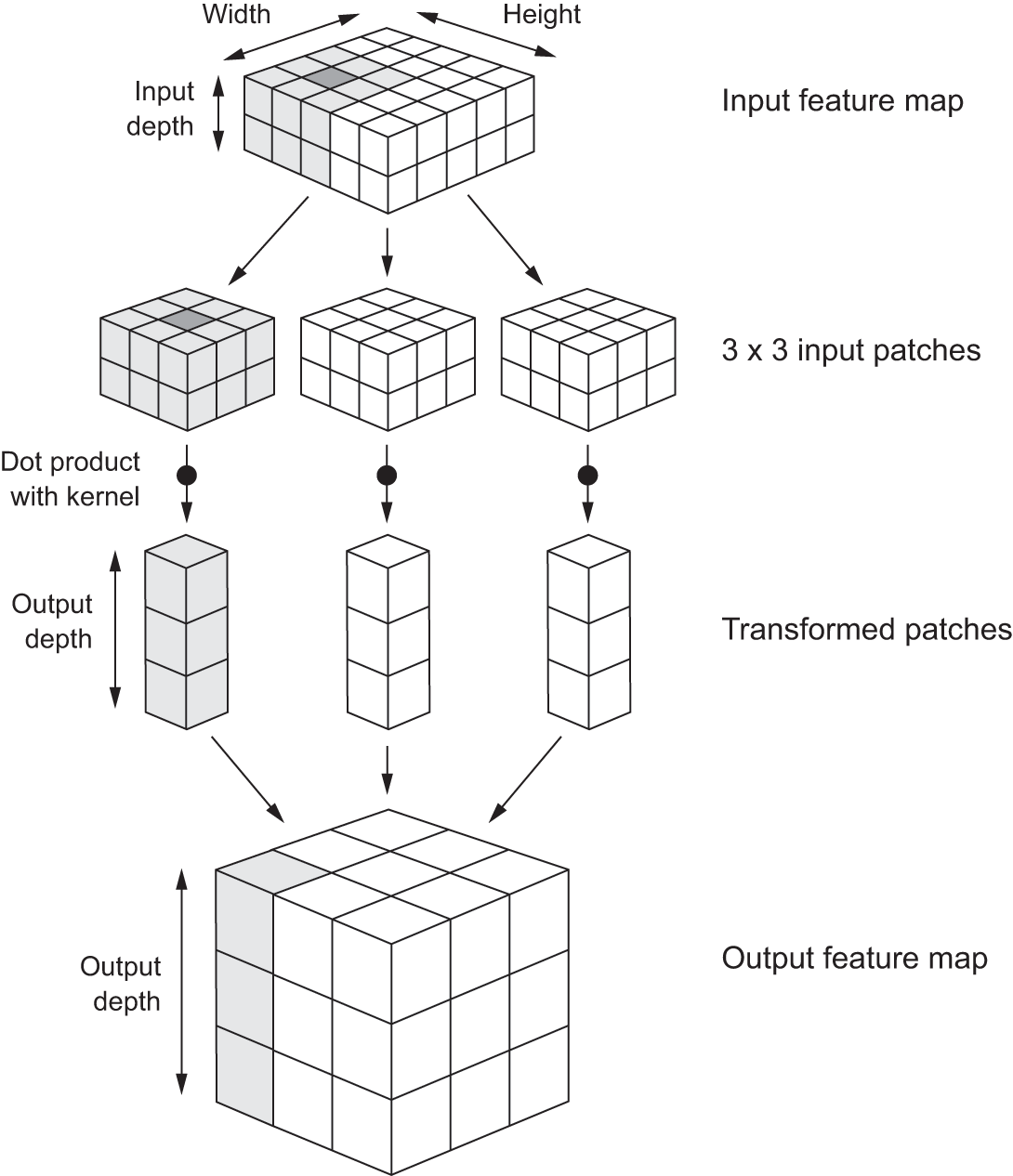

Convolutions operate over rank-3 tensors, called feature maps, with two spatial axes (height and width) as well as a depth axis (also called the channels axis). For an RGB image, the dimension of the depth axis is 3, because the image has three color channels: red, green, and blue. For a black-and-white picture, like the MNIST digits, the depth is 1 (levels of gray). The convolution operation extracts patches from its input feature map and applies the same transformation to all of these patches, producing an output feature map. This output feature map is still a rank-3 tensor: it has a width and a height. Its depth can be arbitrary because the output depth is a parameter of the layer, and the different channels in that depth axis no longer stand for specific colors as in RGB input; rather, they stand for filters. Filters encode specific aspects of the input data: at a high level, a single filter could encode the concept “presence of a face in the input,” for instance.

In the MNIST example, the first convolution layer takes a feature map of size (28, 28, 1) and outputs a feature map of size (26, 26, 64): it computes 64 filters over its input. Each of these 64 output channels contains a 26 × 26 grid of values, which is a response map of the filter over the input, indicating the response of that filter pattern at different locations in the input (see figure 8.3). That is what the term feature map means: every dimension in the depth axis is a feature (or filter), and the rank-2 tensor output[, , n] is the 2D spatial map of the response of this filter over the input.

Convolutions are defined by two key parameters:

Size of the patches extracted from the inputs—These are typically 3 × 3 or 5 × 5. In the example, they were 3 × 3, which is a common choice.

Depth of the output feature map—The number of filters computed by the convolution. The example starts with a depth of 64 and ends with a depth of 256 (64 → 128 → 256).

In Keras Conv2D layers, these parameters are the second and third arguments passed to the layer: layer_conv_2d(, output_depth, c(window_height, window_width)).

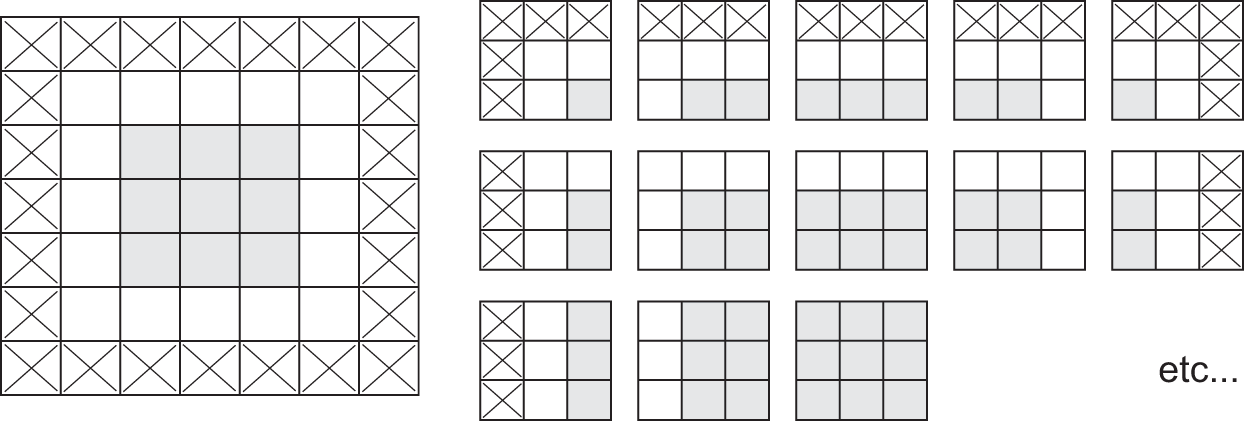

A convolution works by sliding these windows of size 3 × 3 or 5 × 5 over the 3D input feature map, stopping at every possible location, and extracting the 3D patch of surrounding features (shape (window_height, window_width, input_depth)). Each such 3D patch is then transformed into a 1D vector of shape (output_depth), which is done via a tensor product with a learned weight matrix, called the convolution kernel; the same kernel is reused across every patch. All of these vectors (one per patch) are then spatially reassembled into a 3D output map of shape (height, width, output_depth). Every spatial location in the output feature map corresponds to the same location in the input feature map (for example, the lower-right corner of the output contains information about the lower-right corner of the input). For instance, with 3 × 3 windows, the vector output[i, j, ] comes from the 3D patch input[(i-1):(i+1), (j-1):(j+1), ]. The full process is detailed in figure 8.4.

Note that the output width and height may differ from the input width and height. They may differ for two reasons:

- Border effects, which can be countered by padding the input feature map

- The use of strides, which we’ll define in a second

Let’s take a deeper look at these notions.

8.1.1.1 Understanding border effects and padding

Consider a 5 × 5 feature map (25 tiles total). There are only 9 tiles around which we can center a 3 × 3 window, forming a 3 × 3 grid (see figure 8.5). Hence, the output feature map will be 3 × 3. It shrinks a little: by exactly two tiles alongside each dimension, in this case. We can see this border effect in action in the earlier example: we start with 28 × 28 inputs, which become 26 × 26 after the first convolution layer.

If we want to get an output feature map with the same spatial dimensions as the input, we can use padding. Padding consists of adding an appropriate number of rows and columns on each side of the input feature map to make it possible to fit centered convolution windows around every input tile. For a 3 × 3 window, we add one column on the right, one column on the left, one row at the top, and one row at the bottom. For a 5 × 5 window, we add two rows (see figure 8.6).

In Conv2D layers, padding is configurable via the padding argument, which takes two values: "valid", which means no padding (only valid window locations will be used); and "same", which means “pad in such a way as to have an output with the same width and height as the input.” The padding argument defaults to "valid".

8.1.1.2 Understanding convolution strides

The other factor that can influence output size is the notion of strides. The description of convolution so far has assumed that the center tiles of the convolution windows are all contiguous. But the distance between two successive windows is a parameter of the convolution, called its stride, which defaults to 1. It’s possible to have strided convolutions: convolutions with a stride higher than 1. In figure 8.7, we can see the patches extracted by a 3 × 3 convolution with stride 2 over a 5 × 5 input (without padding).

Using stride 2 means the width and height of the feature map are downsampled by a factor of 2 (in addition to any changes induced by border effects). Strided convolutions are rarely used in classification models, but they come in handy for some types of models, as you will see in the next chapter.

In classification models, instead of strides, we tend to use the max-pooling operation to downsample feature maps—which you saw in action in our first convnet example. Let’s look at it in more depth.

8.1.2 The max-pooling operation

In the convnet example, you may have noticed that the size of the feature maps is halved after every MaxPooling2D layer. For instance, before the first MaxPooling2D layer, the feature map is 26 × 26, but the max-pooling operation halves it to 13 × 13. That’s the role of max pooling: to aggressively downsample feature maps, much like strided convolutions.

Max pooling consists of extracting windows from the input feature maps and outputting the maximum value of each channel. It’s conceptually similar to convolution, except that instead of transforming local patches via a learned linear transformation (the convolution kernel), they’re transformed via a hardcoded max tensor operation. A big difference from convolution is that max pooling is usually done with 2 × 2 windows and a stride of 2 to downsample the feature maps by a factor of 2. On the other hand, convolution is typically done with 3 × 3 windows and no stride (stride 1).

Why downsample feature maps this way? Why not remove the max-pooling layers and keep fairly large feature maps all the way up? Let’s look at this option. Our model would then look like this.

inputs <- keras_input(shape = c(28, 28, 1))

outputs <- inputs |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 64, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 128, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 256, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_global_average_pooling_2d() |>

layer_dense(10, activation = "softmax")

model_no_max_pool <- keras_model(inputs = inputs, outputs = outputs)Here’s a summary of the model:

model_no_max_poolModel: "functional_1"

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Layer (type) ┃ Output Shape ┃ Param # ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩

│ input_layer_1 (InputLayer) │ (None, 28, 28, 1) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_3 (Conv2D) │ (None, 26, 26, 64) │ 640 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_4 (Conv2D) │ (None, 24, 24, 128) │ 73,856 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_5 (Conv2D) │ (None, 22, 22, 256) │ 295,168 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ global_average_pooling2d_1 │ (None, 256) │ 0 │

│ (GlobalAveragePooling2D) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ dense_1 (Dense) │ (None, 10) │ 2,570 │

└─────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────────┴───────────────┘

Total params: 372,234 (1.42 MB)

Trainable params: 372,234 (1.42 MB)

Non-trainable params: 0 (0.00 B)

What’s wrong with this setup? Two things:

It isn’t conducive to learning a spatial hierarchy of features. The 3 × 3 windows in the third layer will contain only information coming from 7 × 7 windows in the initial input. The high-level patterns learned by the convnet will still be very small with regard to the initial input, which may not be enough to learn to classify digits (try recognizing a digit by only looking at it through windows that are 7 × 7 pixels!). We need the features from the last convolution layer to contain information about the totality of the input.

The final feature map has dimensions 22 × 22. That’s huge: when we take the average of each 22 × 22 feature map, we are going to be destroying a lot of information compared to when our feature maps were only 3 × 3.

In short, the reason to use downsampling is to reduce the size of the feature maps, making the information they contain increasingly less spatially distributed and increasingly contained in the channels, while also inducing spatial-filter hierarchies by making successive convolution layers “look” at increasingly large windows (in terms of the fraction of the original input image they cover).

Note that max pooling isn’t the only way we can achieve such downsampling. As you already know, we can also use strides in the prior convolution layer. And we can use average pooling instead of max pooling, where each local input patch is transformed by taking the average value of each channel over the patch, rather than the max. But max pooling tends to work better than these alternative solutions. In a nutshell, the reason is that features tend to encode the spatial presence of some pattern or concept over the different tiles of the feature map (hence, the term feature map), and it’s more informative to look at the maximal presence of different features than at their average presence. So the most reasonable subsampling strategy is to first produce dense maps of features (via unstrided convolutions) and then look at the maximal activation of the features over small patches, rather than looking at sparser windows of the inputs (via strided convolutions) or averaging input patches, which could cause us to miss or dilute feature-presence information.

At this point, you should understand the basics of convnets—feature maps, convolution, and max pooling—and you know how to build a small convnet to solve a toy problem such as MNIST digits classification. Now let’s move on to more useful, practical applications.

8.2 Training a convnet from scratch on a small dataset

Having to train an image-classification model using very little data is a common situation, which you’ll likely encounter in practice if you ever do computer vision in a professional context. A “few” samples can mean anywhere from a few hundred to a few tens of thousands of images. As a practical example, we’ll focus on classifying images as dogs or cats. We’ll work with a dataset containing 5,000 pictures of cats and dogs (2,500 cats, 2,500 dogs), taken from the original Kaggle dataset. We’ll use 2,000 pictures for training, 1,000 for validation, and 2,000 for testing.

In this section, we’ll review one basic strategy to tackle this problem: training a new model from scratch using what little data we have. We’ll start by naively training a small convnet on the 2,000 training samples, without any regularization, to set a baseline for what can be achieved. This will get us to a classification accuracy of about 80%. At that point, the main problem will be overfitting. Then we’ll introduce data augmentation, a powerful technique for mitigating overfitting in computer vision. By using data augmentation, we’ll improve the model to reach a test accuracy of about 84%.

In the next section, we’ll review two more essential techniques for applying deep learning to small datasets: feature extraction with a pretrained model and fine-tuning a pretrained model (which will get us to a final accuracy of around 98.5%). Together, these three strategies—training a small model from scratch, doing feature extraction using a pretrained model, and fine-tuning a pretrained model—will constitute your future toolbox for tackling the problem of performing image classification with small datasets.

8.2.1 The relevance of deep learning for small-data problems

What qualifies as “enough samples” to train a model is relative—relative to the size and depth of the model we’re trying to train, for starters. It isn’t possible to train a convnet to solve a complex problem with just a few tens of samples, but a few hundred can potentially suffice if the model is small and well regularized and the task is simple. Because convnets learn local, translation-invariant features, they’re highly data efficient on perceptual problems. Training a convnet from scratch on a very small image dataset will yield reasonable results despite a relative lack of data, without the need for any custom feature engineering. You’ll see this in action in this section.

What’s more, deep-learning models are by nature highly repurposable: we can take, say, an image-classification or speech-to-text model trained on a large-scale dataset and reuse it on a significantly different problem with only minor changes. Specifically, in the case of computer vision, many pretrained classification models are publicly available for download and can be used to bootstrap powerful vision models out of very little data. This is one of the greatest strengths of deep learning: feature reuse. We’ll explore this in the next section. Let’s start by getting our hands on the data.

8.2.2 Downloading the data

The Dogs vs. Cats dataset that we will use isn’t packaged with Keras. It was made available by Kaggle as part of a computer-vision competition in late 2013, back when convnets weren’t mainstream. You can download the original dataset from https://www.kaggle.com/c/dogs-vs-cats/data (you’ll need to create a Kaggle account if you don’t already have one—don’t worry, the process is painless). You can also use the Kaggle API to download the dataset in Colab.

Kaggle makes available an easy-to-use API to programmatically download Kaggle-hosted datasets. You can use it to download the Dogs vs. Cats dataset.

First, you need to do two things from a web browser:

- Go to https://www.kaggle.com/c/dogs-vs-cats/rules and click Join the Competition.

- Go to https://www.kaggle.com/settings, generate a Kaggle API key, and download it as

kaggle.json.

The rest you can do from R. First, move kaggle.json to the ~/.kaggle directory. As a security best practice, make sure the file is readable only by the current user, yourself (this applies only if you’re on Mac or Linux, not Windows):

library(fs)

dir_create("~/.kaggle")

file_move("~/Downloads/kaggle.json", "~/.kaggle/")

file_chmod("~/.kaggle/kaggle.json", "0600")Now you’re ready to download the data. You’ll use uv_run_tool() to run the kaggle command. uv_run_tool() will automatically resolve and install the kaggle utility:

reticulate::uv_run_tool("kaggle competitions download -c dogs-vs-cats")Alternatively, if you are on Colab and can’t conveniently access your Kaggle API key, you can also authenticate through the browser. For this, you can use the kagglehub Python package:

py_require("kagglehub")

kagglehub <- import("kagglehub")

kagglehub$login()Then download the competition data:

kagglehub$competition_download("dogs-vs-cats")The data is downloaded as a compressed zip file, dogs-vs-cats.zip. That zip file contains another compressed zip file, train.zip, which is the training data you’ll use. Uncompress train.zip into a new directory, dogs-vs-cats, using the zip R package (installable from CRAN with install.packages("zip")):

zip::unzip('dogs-vs-cats.zip', exdir = "dogs-vs-cats", files = "train.zip")

zip::unzip("dogs-vs-cats/train.zip", exdir = "dogs-vs-cats")All done!

The pictures in the dataset are medium-resolution color JPEGs. Figure 8.8 shows some examples.

Unsurprisingly, the original dogs-versus-cats Kaggle competition, all the way back in 2013, was won by entrants who used convnets. The best entries achieved up to 95% accuracy. In this example, we will get fairly close to this accuracy (in the next section), even though we will train our models on less than 10% of the data that was available to the competitors.

This dataset contains 25,000 images of dogs and cats (12,500 from each class) and is 543 MB (compressed). After downloading and uncompressing the data, we’ll create a new dataset containing three subsets: a training set with 1,000 samples of each class, a validation set with 500 samples of each class, and a test set with 1,000 samples of each class. Why do this? Because many of the image datasets you’ll encounter in your career contain only a few thousand samples, not tens of thousands. Having more data available would make the problem easier—so it’s good practice to learn with a small dataset.

The subsampled dataset we will work with will have the following directory structure:

fs::dir_tree("dogs_vs_cats_small/", recurse = 1)- 1

- Contains 1,000 cat images

- 2

- Contains 1,000 dog images

- 3

- Contains 1,000 cat images

- 4

- Contains 1,000 dog images

- 5

- Contains 500 cat images

- 6

- Contains 500 dog images

Let’s make it happen in a couple of calls to functions from fs, a user-friendly R package for filesystem operations.

library(fs)

library(glue)

1original_dir <- path("dogs-vs-cats/train")

2new_base_dir <- path("dogs_vs_cats_small")

3make_subset <- function(subset_name, start_index, end_index) {

for (category in c("dog", "cat")) {

file_name <- glue("{category}.{start_index:end_index}.jpg")

dir_create(new_base_dir / subset_name / category)

file_copy(original_dir / file_name,

new_base_dir / subset_name / category / file_name)

}

}

4make_subset("train", start_index = 1, end_index = 1000)

5make_subset("validation", start_index = 1001, end_index = 1500)

6make_subset("test", start_index = 1501, end_index = 2500)- 1

- Path to the directory where the original dataset was uncompressed

- 2

- Directory where we will store our smaller dataset

- 3

-

Utility function to copy cat (respectively, dog) images from index

start_indexto indexend_indexto the subdirectorynew_base_dir/{subset_name}/cat(respectively, dog). “subset_name” will be “train”, “validation”, or “test”. - 4

- Creates the training subset with the first 1,000 images of each category

- 5

- Creates the validation subset with the next 500 images of each category

- 6

- Creates the test subset with the next 1,000 images of each category

So we now have 2,000 training images, 1,000 validation images, and 2,000 test images. Each split contains the same number of samples from each class: this is a balanced binary-classification problem, which means classification accuracy will be an appropriate measure of success.

8.2.3 Building our model

We will reuse the same general model structure you saw in the first example: the convnet will be a stack of alternated Conv2D (with relu activation) and MaxPooling2D layers.

But because we’re dealing with bigger images and a more complex problem, we’ll make our model larger, accordingly: it will have two more Conv2D + MaxPooling2D stages. This serves both to augment the capacity of the model and to further reduce the size of the feature maps so they aren’t overly large when we reach the pooling layer. Here, because we start from inputs of size 180 × 180 pixels (a somewhat arbitrary choice), we end up with feature maps of size 7 × 7 just before the GlobalAveragePooling2D layer.

The depth of the feature maps progressively increases in the model (from 32 to 512), whereas the size of the feature maps decreases (from 180 × 180 to 7 × 7). This is a pattern you’ll see in almost all convnets.

Because we’re looking at a binary classification problem, we’ll end the model with a single unit (a Dense layer of size 1) and a sigmoid activation. This unit will encode the probability that the model is looking at one class or the other.

One last small difference: we will start the model with a Rescaling layer, which will rescale image inputs (whose values are originally in the [0, 255] range) to the [0, 1] range.

1inputs <- keras_input(shape = c(180, 180, 3))

outputs <- inputs |>

2 layer_rescaling(1 / 255) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 64, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 128, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 256, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 512, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

3 layer_global_average_pooling_2d() |>

layer_dense(1, activation = "sigmoid")

model <- keras_model(inputs, outputs)- 1

- The model expects RGB images of size 180 × 180.

- 2

- Rescales inputs to the [0, 1] range by dividing them by 255

- 3

- Flattens the 3D activations with shape (height, width, 512) into 1D activations with shape (512) by averaging them over spatial dimensions

Let’s look at how the dimensions of the feature maps change with every successive layer:

modelModel: "functional_2"

┏━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┃ Layer (type) ┃ Output Shape ┃ Param # ┃

┡━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━╇━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┩

│ input_layer_2 (InputLayer) │ (None, 180, 180, 3) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ rescaling (Rescaling) │ (None, 180, 180, 3) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_6 (Conv2D) │ (None, 178, 178, 32) │ 896 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ max_pooling2d_2 (MaxPooling2D) │ (None, 89, 89, 32) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_7 (Conv2D) │ (None, 87, 87, 64) │ 18,496 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ max_pooling2d_3 (MaxPooling2D) │ (None, 43, 43, 64) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_8 (Conv2D) │ (None, 41, 41, 128) │ 73,856 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ max_pooling2d_4 (MaxPooling2D) │ (None, 20, 20, 128) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_9 (Conv2D) │ (None, 18, 18, 256) │ 295,168 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ max_pooling2d_5 (MaxPooling2D) │ (None, 9, 9, 256) │ 0 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ conv2d_10 (Conv2D) │ (None, 7, 7, 512) │ 1,180,160 │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ global_average_pooling2d_2 │ (None, 512) │ 0 │

│ (GlobalAveragePooling2D) │ │ │

├─────────────────────────────────┼────────────────────────┼───────────────┤

│ dense_2 (Dense) │ (None, 1) │ 513 │

└─────────────────────────────────┴────────────────────────┴───────────────┘

Total params: 1,569,089 (5.99 MB)

Trainable params: 1,569,089 (5.99 MB)

Non-trainable params: 0 (0.00 B)

For the compilation step, we’ll go with the adam optimizer, as usual. Because we ended the model with a single sigmoid unit, we’ll use binary cross-entropy as the loss (as a reminder, check out table 6.1 in chapter 6 for a cheat sheet on what loss function to use in various situations).

model |> compile(

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

optimizer = "adam",

metrics = "accuracy"

)8.2.4 Data preprocessing

As you know by now, data should be formatted into appropriately preprocessed floating-point tensors before being fed into the model. Currently, the data sits on a drive as JPEG files, so the steps for getting it into the model are roughly as follows:

- Read the picture files.

- Decode the JPEG content to RGB grids of pixels.

- Convert these into floating-point tensors.

- Resize them to a shared size (we’ll use 180 × 180).

- Pack them into batches (we’ll use batches of 32 images).

This may seem a bit daunting, but fortunately, Keras has utilities to take care of these steps automatically. In particular, Keras features the utility function image_dataset_from_directory(), which lets us quickly set up a data pipeline that can automatically turn image files on disk into batches of preprocessed tensors. This is what we’ll use here.

Calling image_dataset_from_directory(directory) will first list the subdirectories of directory and assume each one contains images from one of our classes. It will then index the image files in each subdirectory. Finally, it will create and return a tf.data.Dataset object configured to read these files, shuffle them, decode them to tensors, resize them to a shared size, and pack them into batches.

image_dataset_from_directory() to read images from directories

image_size <- shape(180, 180)

batch_size <- 32

train_dataset <-

image_dataset_from_directory(new_base_dir / "train",

image_size = image_size,

batch_size = batch_size)

validation_dataset <-

image_dataset_from_directory(new_base_dir / "validation",

image_size = image_size,

batch_size = batch_size)

test_dataset <-

image_dataset_from_directory(new_base_dir / "test",

image_size = image_size,

batch_size = batch_size)8.2.4.1 Understanding TensorFlow Dataset objects

TensorFlow makes available the tf.data API to create efficient input pipelines for machine learning models. Its core class is tf.data.Dataset.

The Dataset class can be used for data loading and preprocessing in any framework—not just TensorFlow. We can use it together with JAX or PyTorch. When we use it with a Keras model, it works the same, independently of the backend we’re currently using.

A Dataset object is iterable. We can call as_iterator() on it to produce an iterator and then repeatedly call iter_next() on the iterator to generate sequences of data. We will typically use Dataset objects to produce batches of input data and labels. We can pass a Dataset object directly to the fit() method of a Keras model.

The Dataset class handles many key features that would otherwise be cumbersome to implement yourself: in particular, parallelization of the preprocessing logic across multiple CPU cores, as well as asynchronous data prefetching (preprocessing the next batch of data while the previous one is being handled by the model, which keeps execution flowing without interruptions).

The Dataset class also exposes a functional-style API for modifying datasets. To work with tf.data.Dataset, we’ll use the tfdatasets R package. We could also use the methods directly from the tf$data$Dataset submodule and Dataset object. That’s a valid approach too, and it’s safe to mix and match! In this book, we’ll prefer using tf.data through the R package because it provides better ergonomics in R, especially the ability to compose datasets with the pipe (|>). Here’s a quick example: let’s create a Dataset instance from an array of sequential integers. We’ll consider 100 samples, where each sample is a vector of size 6 (in other words, our starting R array is a matrix with shape (100, 6)).

example_array <- array(seq(100*6), c(100, 6))

head(example_array) [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6]

[1,] 1 101 201 301 401 501

[2,] 2 102 202 302 402 502

[3,] 3 103 203 303 403 503

[4,] 4 104 204 304 404 504

[5,] 5 105 205 305 405 505

[6,] 6 106 206 306 406 506- 1

-

Loads tfdatasets and avoids masking

keras3::shape() - 2

-

tensor_slices_dataset()can be used to create aDatasetfrom an array or a list of arrays.

At first, our dataset just yields single samples.

dataset_iterator <- as_iterator(dataset)

for (i in 1:3) {

element <- iter_next(dataset_iterator)

print(element)

}tf.Tensor([ 1 101 201 301 401 501], shape=(6), dtype=int32)

tf.Tensor([ 2 102 202 302 402 502], shape=(6), dtype=int32)

tf.Tensor([ 3 103 203 303 403 503], shape=(6), dtype=int32)We can use the dataset_batch() method to batch the data.

batched_dataset <- dataset |> dataset_batch(3)

batched_dataset_iterator <- as_iterator(batched_dataset)

for (i in 1:3) {

element <- iter_next(batched_dataset_iterator)

print(element)

}tf.Tensor(

[[ 1 101 201 301 401 501]

[ 2 102 202 302 402 502]

[ 3 103 203 303 403 503]], shape=(3, 6), dtype=int32)

tf.Tensor(

[[ 4 104 204 304 404 504]

[ 5 105 205 305 405 505]

[ 6 106 206 306 406 506]], shape=(3, 6), dtype=int32)

tf.Tensor(

[[ 7 107 207 307 407 507]

[ 8 108 208 308 408 508]

[ 9 109 209 309 409 509]], shape=(3, 6), dtype=int32)More broadly, we have access to a range of useful dataset methods, such as these:

dataset_shuffle(buffer_size)shuffles elements within a buffer.dataset_prefetch(buffer_size)prefetches a buffer of elements in memory to achieve better GPU utilization.dataset_map(callable)applies an arbitrary transformation to each element of the dataset (the functioncallable, expected to take as input a single element yielded by the dataset).

The method dataset_map(function, num_parallel_calls) in particular is one that you will use often. Here’s an example: let’s use it to reshape the elements in our toy dataset from shape (6) to shape (2, 3).

dataset_map()

reshaped_dataset <- dataset |>

dataset_map(\(element) tf$reshape(element, shape(2, 3)))

reshaped_dataset_iterator <- as_iterator(reshaped_dataset)

for (i in 1:3) {

element <- iter_next(reshaped_dataset_iterator)

print(element)

}tf.Tensor(

[[ 1 101 201]

[301 401 501]], shape=(2, 3), dtype=int32)

tf.Tensor(

[[ 2 102 202]

[302 402 502]], shape=(2, 3), dtype=int32)

tf.Tensor(

[[ 3 103 203]

[303 403 503]], shape=(2, 3), dtype=int32)You’ll see more dataset_map() action in the upcoming chapters.

8.2.4.2 Fitting the model

Let’s look at the output of one of these Dataset objects: it yields batches of 180 × 180 RGB images (shape (32, 180, 180, 3)) and integer labels (shape (32)). There are 32 samples in each batch (the batch size).

Dataset

.[data_batch, labels_batch] <- train_dataset |> as_iterator() |> iter_next()

op_shape(data_batch)shape(32, 180, 180, 3)op_shape(labels_batch)shape(32)Let’s fit the model on our dataset. We use the validation_data argument in fit() to monitor validation metrics on a separate Dataset object.

Note that we also use a ModelCheckpoint callback to save the model after each epoch. We configure it with the path where to save the file, as well as the arguments save_best_only=TRUE and monitor="val_loss": they tell the callback to save a new file (overwriting any previous one) only when the current value of the val_loss metric is less than at any previous time during training. This guarantees that our saved file will always contain the state of the model corresponding to its best-performing training epoch, in terms of its performance on the validation data. As a result, we won’t have to retrain a new model for fewer epochs if we start overfitting: we can just reload our saved file.

Dataset

callbacks <- list(

callback_model_checkpoint(

filepath = "convnet_from_scratch.keras",

save_best_only = TRUE,

monitor = "val_loss"

)

)

history <- model |> fit(

train_dataset,

epochs = 50,

validation_data = validation_dataset,

callbacks = callbacks

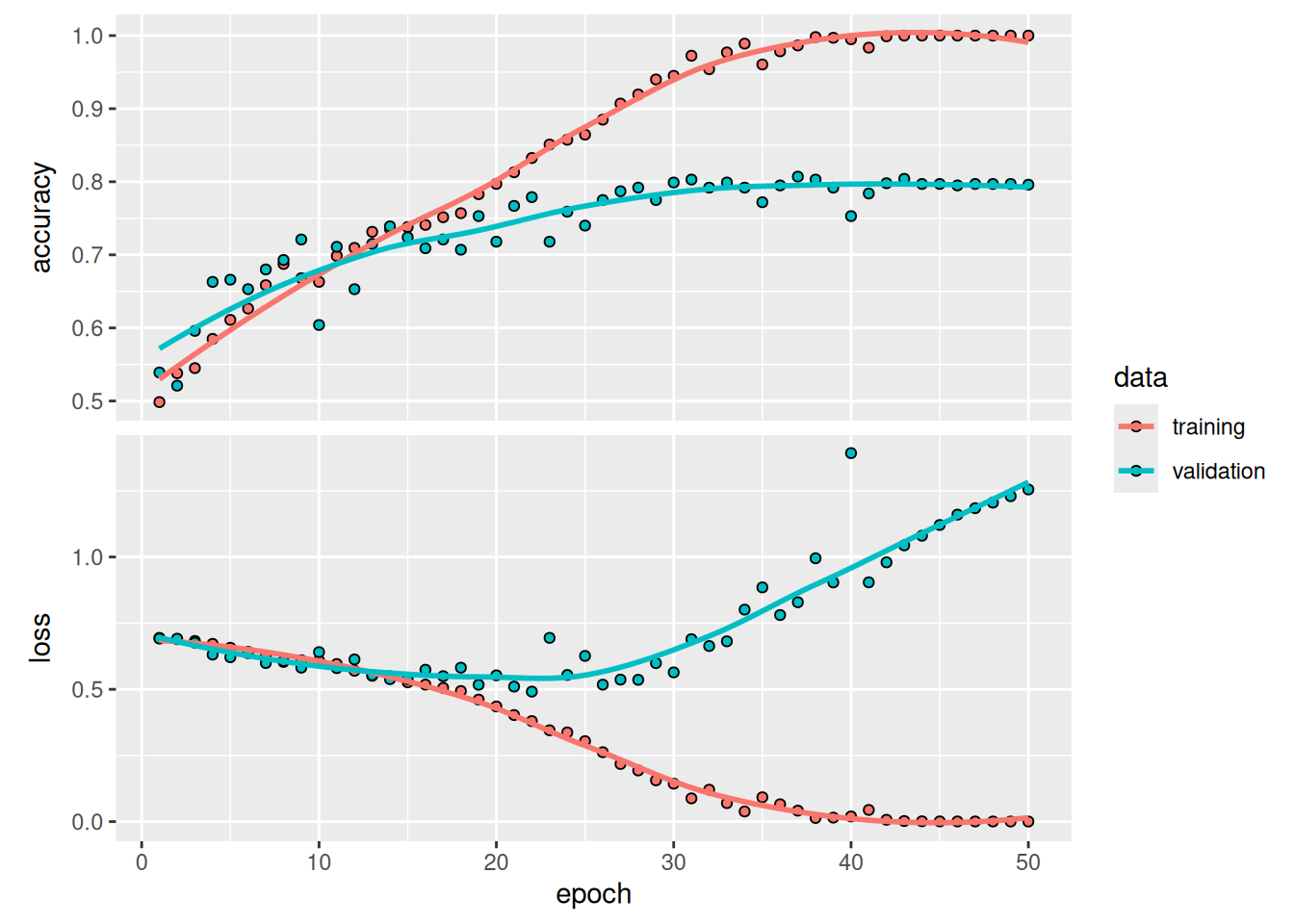

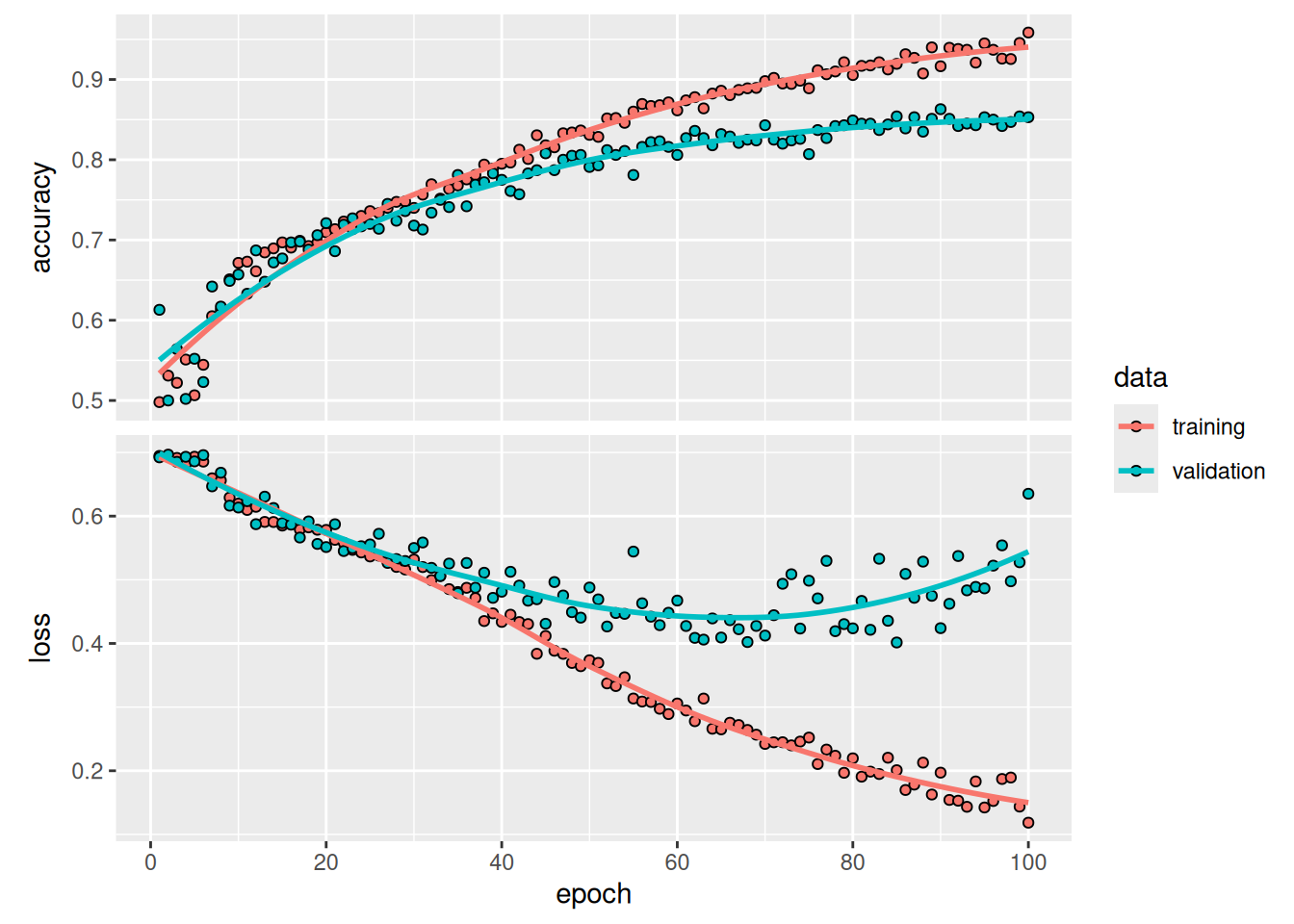

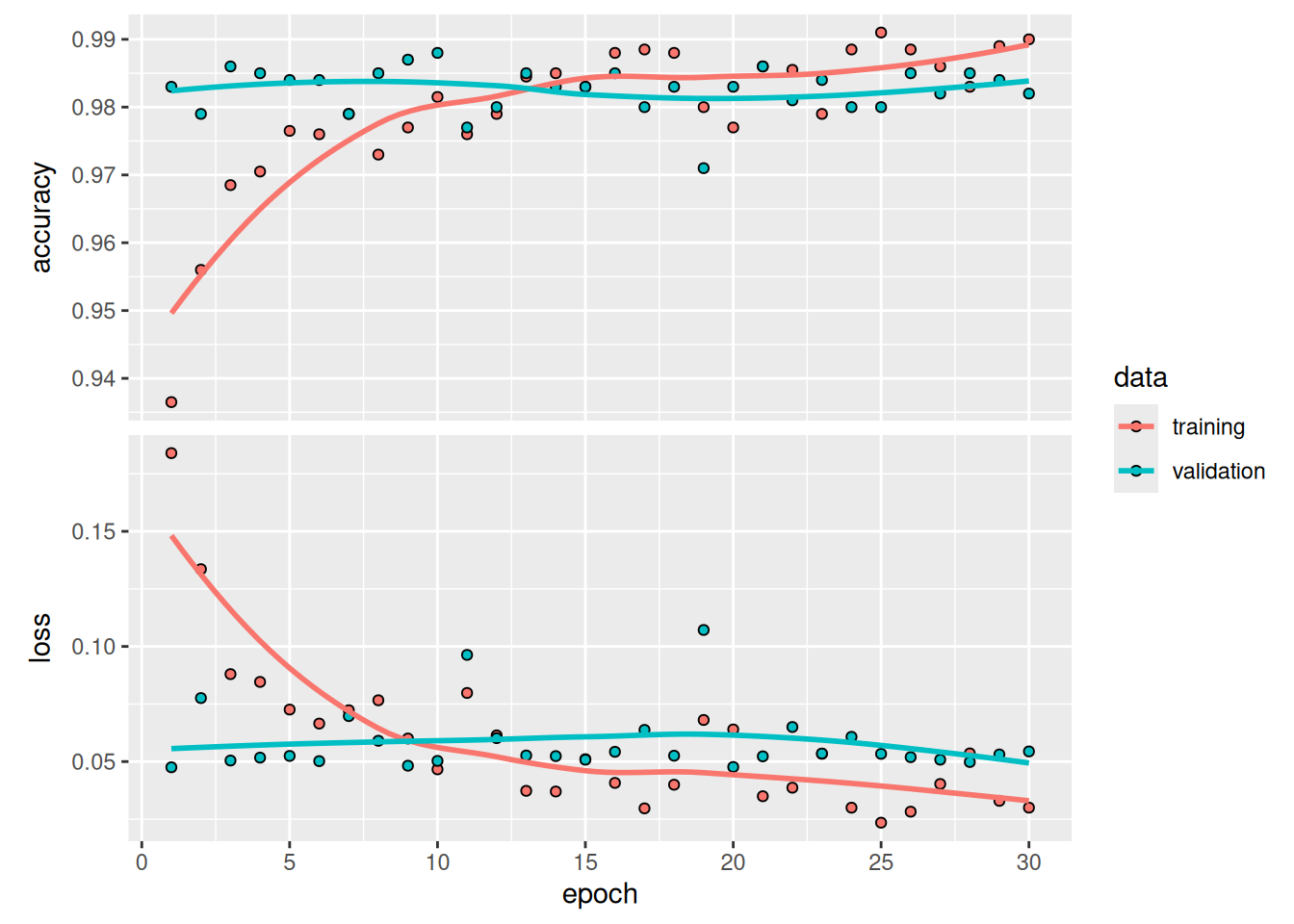

)Let’s plot the loss and accuracy of the model over the training and validation data during training (see Figure 8.9).

plot(history)These plots are characteristic of overfitting. The training accuracy increases linearly over time until it reaches nearly 100%, whereas the validation accuracy peaks around 80%. The validation loss reaches its minimum after only 10 epochs and then stalls, whereas the training loss keeps decreasing linearly as training proceeds.

Let’s check the test accuracy. We’ll reload the model from its saved file to evaluate it as it was before it started overfitting.

test_model <- load_model("convnet_from_scratch.keras")

result <- evaluate(test_model, test_dataset)

cat(sprintf("Test accuracy: %.3f\n", result$accuracy))Test accuracy: 0.789We get a test accuracy of 78.9% (due to the randomness of neural network initializations, you may get numbers within a few percentage points of that).

Because we have relatively few training samples (2,000), overfitting will be our primary concern. We already know about a number of techniques that can help mitigate overfitting, such as dropout and weight decay (L2 regularization). We’re now going to work with a new one, specific to computer vision and used almost universally when processing images with deep learning models: data augmentation.

8.2.5 Using data augmentation

Overfitting is caused by having too few samples to learn from, rendering us unable to train a model that can generalize to new data. Given infinite data, our model would be exposed to every possible aspect of the data distribution at hand: we would never overfit. Data augmentation takes the approach of generating more training data from existing training samples by augmenting the samples via a number of random transformations that yield believable-looking images. The goal is that at training time, our model will never see the exact same picture twice. This helps expose the model to more aspects of the data and generalize better.

In Keras, this can be done via data augmentation layers. Such layers can be added in one of two ways:

- At the start of the model—inside the model. In our case, the layers would come right before the

Rescalinglayer. - Inside the data pipeline—outside the model. In our case, we’d apply them to our

Datasetvia adataset_map()call.

The main difference between these two options is that data augmentation done inside the model runs on the GPU, just like the rest of the model. Meanwhile, data augmentation done in the data pipeline runs on the CPU, typically in a parallel way on multiple CPU cores. Sometimes there can be performance benefits to doing the former, but the latter is usually the better option. So let’s go with that!

1data_augmentation_layers <- list(

layer_random_flip(, "horizontal"),

layer_random_rotation(, 0.1),

layer_random_zoom(, 0.2)

)

2data_augmentation <- function(images, targets) {

for (layer in data_augmentation_layers)

images <- layer(images)

list(images, targets)

}

augmented_train_dataset <- train_dataset |>

3 dataset_map(data_augmentation, num_parallel_calls = 8) |>

4 dataset_prefetch()- 1

- Defines the transformations to apply, as a list

- 2

- Creates a function that applies them sequentially

- 3

- Maps this function into the dataset

- 4

- Enables prefetching of batches to concurrently do data preprocessing on the CPU and model training on the GPU; important for best performance

Note that we leave the first argument to the augmentation layer calls missing.

When the first argument to a layer function is missing or NULL, the return value is the layer instance itself. This is useful when we want to instantiate a layer without composing it yet.

To compose the layer later, we can call the instance like a function. For example, these two approaches produce the same result:

layer <- layer_random_flip(, "horizontal")

result <- layer(object)result <- object |> layer_random_flip("horizontal")These are just a few of the layers available (for more, see the Keras documentation). Let’s quickly go over this code:

layer_random_flip(, "horizontal")applies horizontal flipping to a random 50% of the images that go through it.layer_random_rotation(, 0.1)rotates the input images by a random value in the range [-10%, +10%] (these are fractions of a full circle; in degrees, the range would be [-36 degrees, +36 degrees]).layer_random_zoom(, 0.2)zooms in or out of the image by a random factor in the range [-20%, +20%].

Let’s look at the augmented images (see figure 8.10).

batch <- train_dataset |> as_iterator() |> iter_next()

.[images, labels] <- batch

par(mfrow = c(3, 3), mar = rep(.5, 4))

image <- images[1, , , ]

1plot(as.raster(image, max = 255))

for (i in 2:9) {

2 .[augmented_images, ..] <- data_augmentation(images, NULL)

3 augmented_image <- augmented_images@r[1] |> as.array()

plot(as.raster(augmented_image, max = 255))

}- 1

- Plots the first image of the batch, without augmentation

- 2

- Applies the augmentation stage to the batch of images

- 3

- Displays the first image in the output batch. For each of the eight iterations, this is a different augmentation of the same image.

If we train a new model using this data-augmentation configuration, the model will never see the same input twice. But the inputs it sees are still heavily intercorrelated, because they come from a small number of original images—we can’t produce new information, we can only remix existing information. As such, this may not be enough to completely get rid of overfitting. To further fight overfitting, we’ll also add a Dropout layer to our model, right before the densely connected classifier.

inputs <- keras_input(shape = c(180, 180, 3))

outputs <- inputs |>

layer_rescaling(1 / 255) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 32, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 64, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 128, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 256, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = 2) |>

layer_conv_2d(filters = 512, kernel_size = 3, activation = "relu") |>

layer_global_average_pooling_2d() |>

layer_dropout(0.25) |>

layer_dense(1, activation = "sigmoid")

model <- keras_model(inputs, outputs)

model |> compile(

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

optimizer = "adam",

metrics = "accuracy"

)Let’s train the model using data augmentation and dropout. Because we expect overfitting to occur much later during training, we will train for twice as many epochs: 100. Note that we evaluate on images that aren’t augmented—data augmentation is usually only performed at training time, as it is a regularization technique.

callbacks <- list(

callback_model_checkpoint(

filepath = "convnet_from_scratch_with_augmentation.keras",

save_best_only = TRUE,

monitor = "val_loss"

)

)

history <- model |> fit(

augmented_train_dataset,

1 epochs = 100,

validation_data = validation_dataset,

callbacks = callbacks

)- 1

- Because we expect the model to overfit more slowly, we train for more epochs.

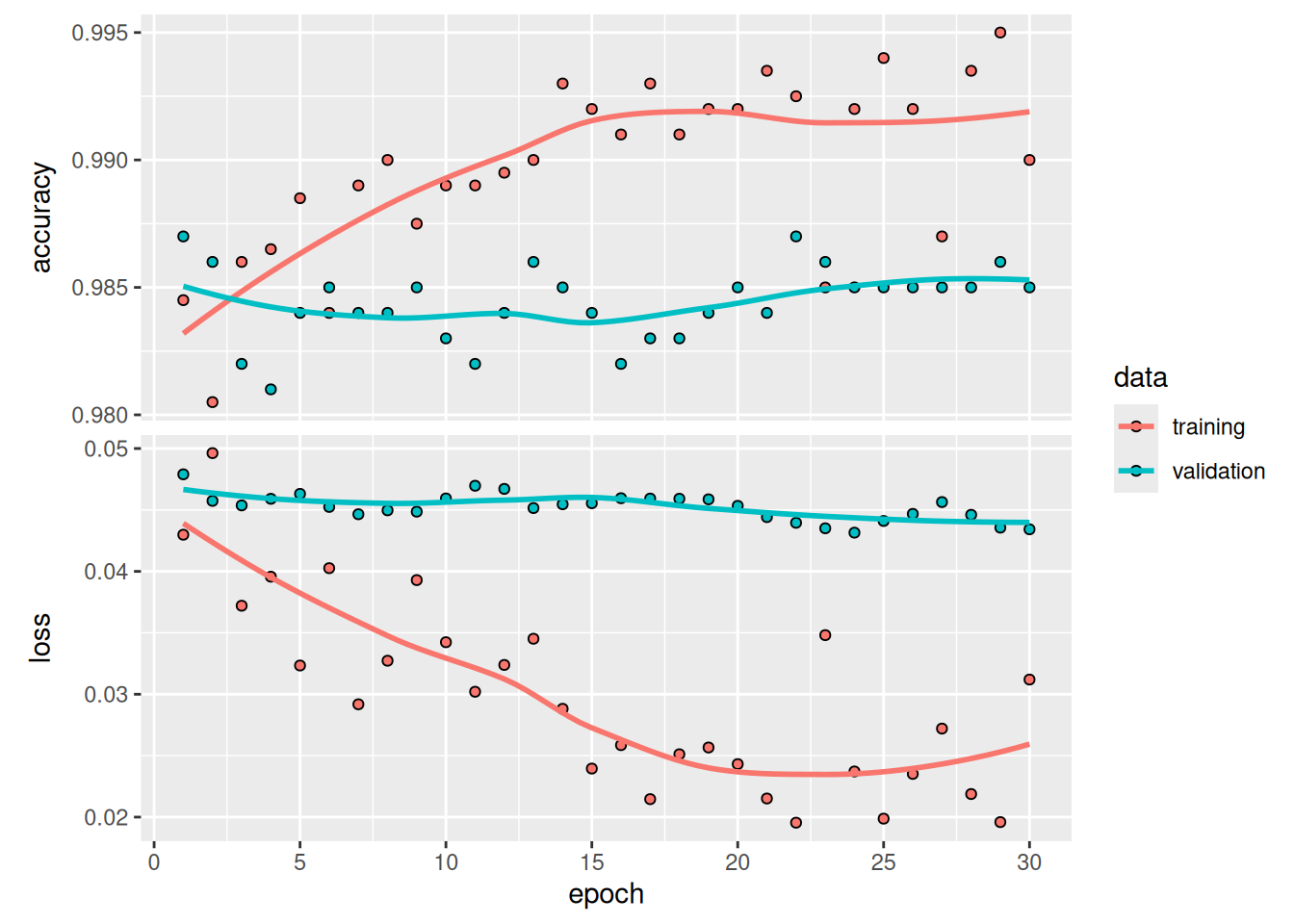

Let’s plot the results again; see figure 8.11. Thanks to data augmentation and dropout, we start overfitting much later, around epochs 60–70 (compared to epoch 10 for the original model). The validation accuracy ends up peaking above 85%—a big improvement over our first try.

Let’s check the test accuracy.

test_model <- load_model("convnet_from_scratch_with_augmentation.keras")

result <- evaluate(test_model, test_dataset)

cat(sprintf("Test accuracy: %.3f\n", result$accuracy))Test accuracy: 0.830We get a test accuracy of 83.0%. It’s starting to look good! If you’re using Colab, be sure to download the saved file (convnet_from_scratch_with_augmentation.keras), as you will use it for some experiments in the next chapter.

By further tuning the model’s configuration (such as the number of filters per convolution layer or the number of layers in the model), we may be able to get an even better accuracy, likely up to 90%. But it would be difficult to go any higher just by training our own convnet from scratch because we have so little data to work with. As a next step to improve our accuracy on this problem, we’ll have to use a pretrained model, which is the focus of the next two sections.

8.3 Using a pretrained model

A common and highly effective approach to deep learning on small image datasets is to use a pretrained model: a model that was previously trained on a large dataset, typically on a large-scale image-classification task. If this original dataset is large enough and general enough, then the spatial hierarchy of features learned by the pretrained model can effectively act as a generic model of the visual world, and hence its features can prove useful for many different computer vision problems, even though these new problems may involve completely different classes than those of the original task. For instance, we might train a model on ImageNet (where classes are mostly animals and everyday objects) and then repurpose this trained model for something as remote as identifying furniture items in images. Such portability of learned features across different problems is a key advantage of deep learning compared to many older, shallow learning approaches, and it makes deep learning very effective for small-data problems.

In this case, let’s consider a large convnet trained on the ImageNet dataset (1.4 million labeled images and 1,000 different classes). ImageNet contains many animal classes, including different species of cats and dogs, and we can thus expect it to perform well on the dogs-versus-cats classification problem.

We’ll use the Xception architecture. This may be your first encounter with one of these cutesy model names: Xception, ResNet, EfficientNet, and so on. You’ll get used to them if you keep doing deep learning for computer vision because they will come up frequently. You’ll learn about the architectural details of Xception in the next chapter.

There are two ways to use a pretrained model: feature extraction and fine-tuning. We’ll cover both of them. Let’s start with feature extraction.

8.3.1 Feature extraction with a pretrained model

Feature extraction consists of using the representations learned by a previously trained model to extract interesting features from new samples. These features are then run through a new classifier, which is trained from scratch.

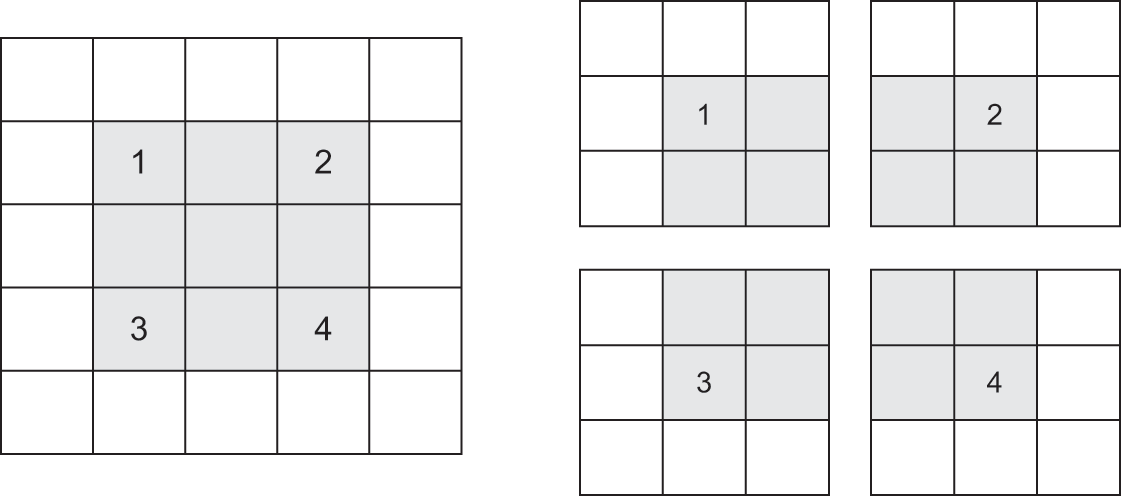

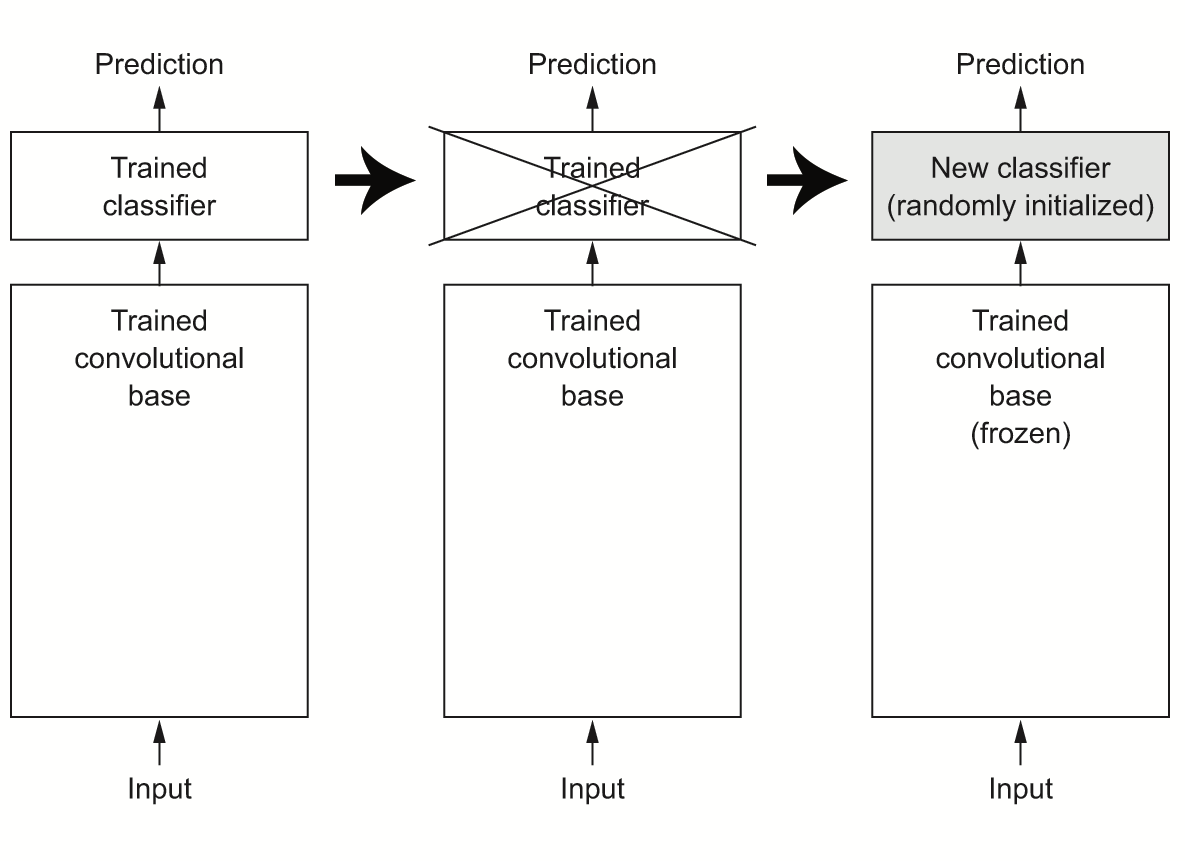

As you saw previously, convnets used for image classification comprise two parts: they start with a series of pooling and convolution layers, and they end with a densely connected classifier. The first part is called the convolutional base or backbone of the model. In the case of convnets, feature extraction consists of taking the convolutional base of a previously trained network, running the new data through it, and training a new classifier on top of the output (see figure 8.12).

Why reuse only the convolutional base? Could we reuse the densely connected classifier as well? In general, doing so should be avoided. The reason is that the representations learned by the convolutional base are likely to be more generic and therefore more reusable: the feature maps of a convnet are presence maps of generic concepts over a picture, which is likely to be useful regardless of the computer vision problem at hand. But the representations learned by the classifier will necessarily be specific to the set of classes on which the model was trained: they will only contain information about the presence probability of this or that class in the entire picture. Additionally, representations found in densely connected layers no longer contain any information about where objects are located in the input image: these layers get rid of the notion of space, whereas the object location is still described by convolutional feature maps. For problems where object location matters, densely connected features are largely useless.

Note that the level of generality (and therefore reusability) of the representations extracted by specific convolution layers depends on the depth of the layer in the model. Layers that come earlier in the model extract local, highly generic feature maps (such as visual edges, colors, and textures), whereas layers that are higher up extract more-abstract concepts (such as “cat ear” and “dog eye”). So if our new dataset differs a lot from the dataset on which the original model was trained, we may be better off using only the first few layers of the model to do feature extraction, rather than using the entire convolutional base.

In this case, because the ImageNet class set contains multiple dog and cat classes, it’s likely to be beneficial to reuse the information contained in the densely connected layers of the original model. But we’ll choose not to, so we can cover the more general case where the class set of the new problem doesn’t overlap the class set of the original model. Let’s put this into practice by using the convolutional base of our pretrained model to extract interesting features from cat and dog images and then train a dogs-versus-cats classifier on top of these features.

We will use the KerasHub library to create all the pretrained models used in this book. KerasHub contains Keras implementations of popular pretrained model architectures paired with pretrained weights that can be downloaded to your machine. It contains a number of convnets like Xception, ResNet, EfficientNet, and MobileNet, as well as larger, generative models we will use in the later chapters of this book. Let’s try using it to instantiate the Xception model trained on the ImageNet dataset.

KerasHub is a separate package from Keras. To use it, first declare it as a requirement with py_require("keras-hub"). If reticulate is managing Python dependencies in an ephemeral environment (the default), it will automatically download and install the package if needed.

If you are managing your own Python environment, you can install it manually with pip install keras-hub.

py_require("keras-hub")

keras_hub <- import("keras_hub")

conv_base <- keras_hub$models$Backbone$from_preset("xception_41_imagenet")You’ll note a couple of things. First, KerasHub uses the term backbone to refer to the underlying feature extractor network without the classification head (it’s a little easier to type than “convolutional base”). It also uses a special constructor called from_preset() that will download the configuration and weights for the Xception model.

What’s that “41” in the name of the model we are using? Pretrained convnets are by convention often named by how “deep” they are. In this case, the 41 means that our Xception model has 41 trainable layers (conv and dense layers) stacked on top of each other. It’s the “deepest” model we’ve used so far in the book by a good margin.

There’s one more missing piece we need before we can use this model. Every pretrained convnet will do some rescaling and resizing of images before pretraining. It’s important to make sure our input images match; otherwise, our model will need to relearn how to extract features from images with a totally different input range. Rather than keep track of which pretrained models use a [0, 1] input range for pixel values and which use a [-1, 1] range, we can use a KerasHub layer called ImageConverter that will rescale our images to match our pretrained checkpoint. It has the same special from_preset() constructor as the backbone class.

preprocessor <- keras_hub$layers$ImageConverter$from_preset(

"xception_41_imagenet",

image_size = shape(180, 180)

)At this point, there are two ways we can proceed:

Running the convolutional base over our dataset, recording its output to an array on disk, and then using this data as input to a standalone, densely connected classifier similar to those you saw in part 1 of this book. This solution is fast and cheap to run, because it requires running the convolutional base only once for every input image, and the convolutional base is by far the most expensive part of the pipeline. But for the same reason, this technique won’t allow us to use data augmentation.

Extending the model we have (

conv_base) by addingDenselayers on top and running the whole thing end to end on the input data. This will allow us to use data augmentation because every input image goes through the convolutional base every time it’s seen by the model. But for the same reason, this technique is far more expensive than the first.

We’ll cover both techniques. Let’s walk through the code required to set up the first one: recording the output of conv_base on our data and using these outputs as inputs to a new model.

8.3.1.1 Fast feature extraction without data augmentation

We’ll start by extracting features as arrays by calling the predict() method of the conv_base model on our training, validation, and testing datasets. Let’s iterate over our datasets to extract the pretrained model’s features.

get_features_and_labels <- function(dataset) {

dataset |>

as_array_iterator() |>

iterate(function(batch) {

.[images, labels] <- batch

preprocessed_images <- preprocessor(images)

features <- conv_base |> predict(preprocessed_images, verbose = 0)

tibble::tibble(features, labels)

}) |>

dplyr::bind_rows()

}

.[train_features, train_labels] <- get_features_and_labels(train_dataset)

.[val_features, val_labels] <- get_features_and_labels(validation_dataset)

.[test_features, test_labels] <- get_features_and_labels(test_dataset)The extracted features are currently of shape (samples, 6, 6, 2048):

dim(train_features)[1] 2000 6 6 2048At this point, we can define our densely connected classifier (note the use of dropout for regularization) and train it on the data and labels we just recorded.

inputs <- keras_input(shape = c(6, 6, 2048))

outputs <- inputs |>

1 layer_global_average_pooling_2d() |>

layer_dense(256, activation = "relu") |>

layer_dropout(0.25) |>

layer_dense(1, activation = "sigmoid")

model <- keras_model(inputs, outputs)

model |> compile(

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

optimizer = "adam",

metrics = "accuracy"

)

callbacks <- list(

callback_model_checkpoint(

filepath = "feature_extraction.keras",

save_best_only = TRUE,

monitor = "val_loss"

)

)

history <- model |> fit(

train_features, train_labels,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = list(val_features, val_labels),

callbacks = callbacks

)- 1

- Average spatial dimensions to “flatten” the feature map

Training is very fast because we only have to deal with two Dense layers: an epoch takes less than 1 second even on a CPU.

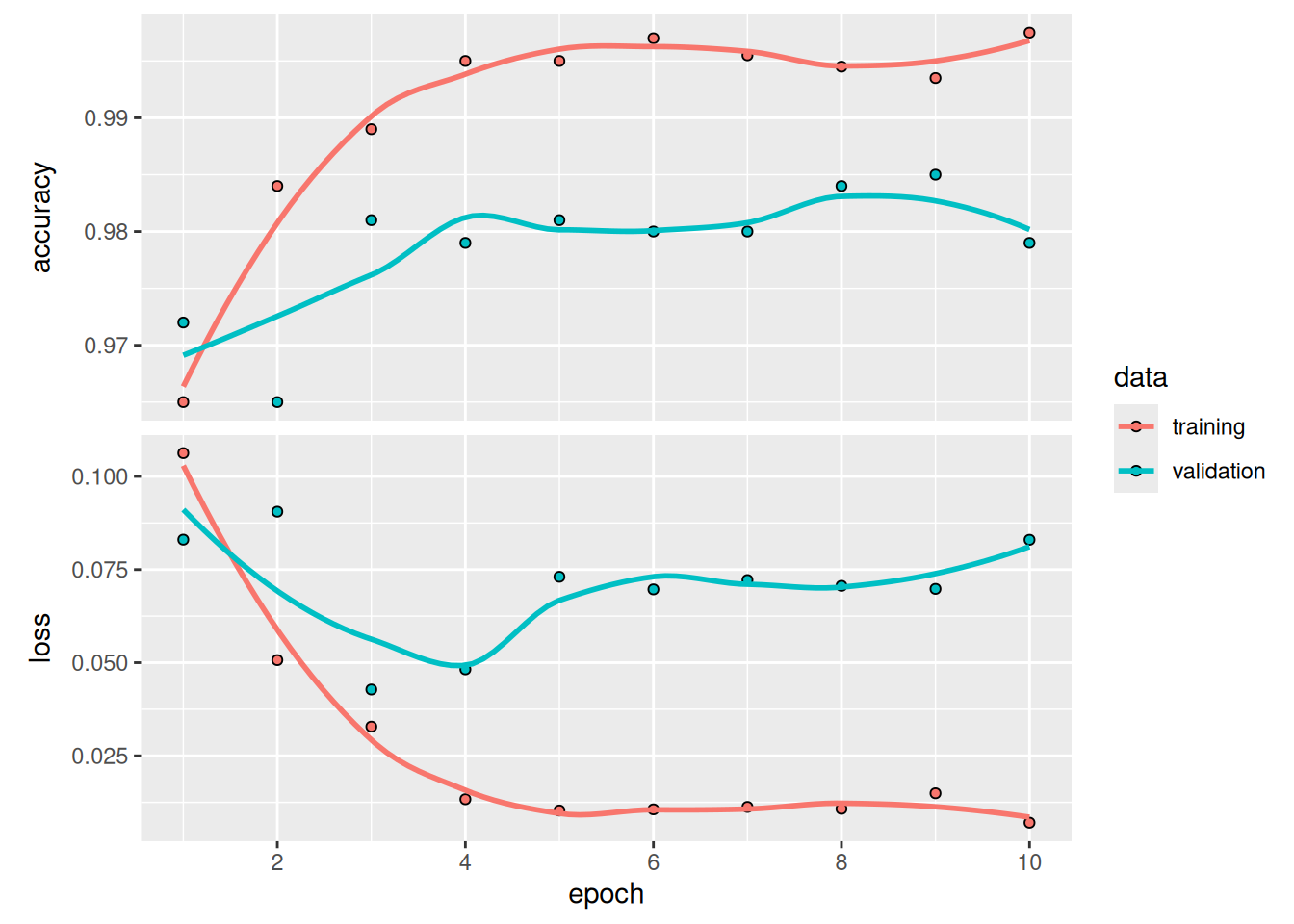

Let’s look at the loss and accuracy curves during training (see figure 8.13).

plot(history)We reach a validation accuracy of slightly over 98%: much better than we achieved in the previous section with the small model trained from scratch. This is a bit of an unfair comparison, however, because ImageNet contains many dog and cat instances, which means that our pretrained model already has the exact knowledge required for the task at hand. This won’t always be the case when you use pretrained features.

However, the plots also indicate that we’re overfitting almost from the start—despite using dropout with a fairly large rate. That’s because this technique doesn’t use data augmentation, which is essential for preventing overfitting with small image datasets.

Let’s check the test accuracy:

test_model <- load_model("feature_extraction.keras")

result <- evaluate(test_model, test_features, test_labels)

cat(sprintf("Test accuracy: %.3f\n", result$accuracy))Test accuracy: 0.984We get test accuracy of 98.4%—a very nice improvement over training a model from scratch!

8.3.1.2 Feature extraction together with data augmentation

Now, let’s review the second technique we mentioned for doing feature extraction, which is much slower and more expensive but allows us to use data augmentation during training: creating a model that chains the conv_base with a new dense classifier, and training it end to end on the inputs.

To do this, we will first freeze the convolutional base. Freezing a layer or set of layers means preventing their weights from being updated during training. Here, if we don’t do this, then the representations that were previously learned by the convolutional base will be modified during training. Because the Dense layers on top are randomly initialized, very large weight updates will be propagated through the network, effectively destroying the representations previously learned.

In Keras, we freeze a layer or model by setting its trainable attribute to FALSE, or by calling freeze_weights().

conv_base <- keras_hub$models$Backbone$from_preset(

"xception_41_imagenet",

trainable = FALSE

)Setting trainable to FALSE empties the list of trainable weights of the layer or model.

1unfreeze_weights(conv_base)

length(conv_base$trainable_weights)- 1

- The number of trainable weights before freezing the conv base

[1] 1541freeze_weights(conv_base)

length(conv_base$trainable_weights)- 1

- The number of trainable weights after freezing the conv base

[1] 0Now we can create a new model that chains together our frozen convolutional base and a dense classifier, like this:

inputs <- keras_input(shape=c(180, 180, 3))

outputs <- inputs |>

preprocessor() |>

conv_base() |>

layer_global_average_pooling_2d() |>

layer_dense(256) |>

layer_dropout(0.25) |>

layer_dense(1, activation = "sigmoid")

model <- keras_model(inputs, outputs)

model |> compile(

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

optimizer = "adam",

metrics = "accuracy"

)With this setup, only the weights from the two Dense layers that we added will be trained. That’s a total of four weight tensors: two per layer (the main weight matrix and the bias vector). Note that for these changes to take effect, we must first compile the model. If we ever modify weight trainability after compilation, we should then recompile the model, or these changes will be ignored.

Let’s train our model. We’ll reuse our augmented dataset augmented_train_dataset. Thanks to data augmentation, it will take much longer for the model to start overfitting, so we can train for more epochs—let’s do 30:

callbacks <- list(

callback_model_checkpoint(

filepath = "feature_extraction_with_data_augmentation.keras",

save_best_only = TRUE,

monitor = "val_loss"

)

)

history <- model |> fit(

augmented_train_dataset,

epochs = 30,

validation_data = validation_dataset,

callbacks = callbacks

)This technique is expensive enough that you should attempt it only if you have access to a GPU (such as the free GPU available in Colab)—it’s intractable on a CPU. If you can’t run your code on a GPU, then the previous technique is the way to go.

Let’s plot the results again (see figure 8.14). This model reaches a validation accuracy of 98.2%.

Let’s check the test accuracy.

test_model <- load_model("feature_extraction_with_data_augmentation.keras")

result <- evaluate(test_model, test_dataset)

cat(sprintf("Test accuracy: %.3f\n", result$accuracy))Test accuracy: 0.980We get a test accuracy of 98.0%. This is barely an improvement over the previous model, which is a bit disappointing. It could be a sign that our data augmentation configuration does not exactly match the distribution of the test data. Let’s see if we can do better with our latest attempt.

8.3.2 Fine-tuning a pretrained model

Another widely used technique for model reuse, complementary to feature extraction, is fine-tuning. Fine-tuning consists of unfreezing the frozen model base used for feature extraction and jointly training both the newly added part of the model (in this case, the fully connected classifier) and the base model. This is called fine-tuning because it slightly adjusts the more abstract representations of the model being reused to make them more relevant for the problem at hand.

We stated earlier that it’s necessary to freeze the pretrained convolution base first to be able to train a randomly initialized classifier on top. For the same reason, it’s possible to fine-tune the convolutional base only once the classifier on top has already been trained. If the classifier isn’t already trained, then the error signal propagating through the network during training will be too large, and the representations previously learned by the layers being fine-tuned will be destroyed. Thus, the steps for fine-tuning a network are as follows:

- Add our custom network on top of an already-trained base network.

- Freeze the base network.

- Train the part we added.

- Unfreeze the base network.

- Jointly train both these layers and the part we added.

Note that we should not unfreeze “batch normalization” layers (BatchNormalization). Batch normalization and its effect on fine-tuning are explained in the next chapter.

We already completed the first three steps when doing feature extraction. Let’s proceed with step 4: we’ll unfreeze our conv_base.

In this case, we choose to unfreeze and fine-tune the entire Xception convolutional base. However, when dealing with large pretrained models, we may sometimes only unfreeze some of the top layers of the convolutional base and leave the lower layers frozen. You’re probably wondering, why fine-tune only some of the layers? Why the top ones specifically? Here’s why:

Earlier layers in the convolutional base encode more-generic, reusable features, whereas layers higher up encode more-specialized features. It’s more useful to fine-tune the more-specialized features because those are the ones that need to be repurposed for our new problem. There would be fast-decreasing returns in fine-tuning lower layers.

The more parameters we’re training, the more we’re at risk of overfitting. The convolutional base has 15 million parameters, so it would be risky to attempt to train it on our small dataset.

Thus, it can be a good strategy to fine-tune only the top three or four layers in the convolutional base. We’d do something like this:

conv_base$trainable <- TRUE

for (layer in head(conv_base$layers, -4))

layer$trainable <- FALSEOr more simply:

unfreeze_weights(conv_base, from = -4)Let’s start fine-tuning the model using a very low learning rate. The reason for using a low learning rate is that we want to limit the magnitude of the modifications we make to the representations of the layers we’re fine-tuning. Updates that are too large may harm these representations.

model |> compile(

loss = "binary_crossentropy",

optimizer = optimizer_adam(learning_rate = 1e-5),

metrics = "accuracy"

)

callbacks <- list(

callback_model_checkpoint(

filepath = "fine_tuning.keras",

save_best_only = TRUE,

monitor = "val_loss"

)

)

history <- model |> fit(

augmented_train_dataset,

epochs = 30,

validation_data = validation_dataset,

callbacks = callbacks

)We can now finally evaluate this model on the test data (see figure 8.15):

model <- load_model("fine_tuning.keras")

result <- evaluate(model, test_dataset)

cat(sprintf("Test accuracy: %.3f\n", result$accuracy))Test accuracy: 0.986Here, we get a test accuracy of 98.6% (again, your own results may be within half a percentage point). In the original Kaggle competition around this dataset, this would have been one of the top results. It’s not quite a fair comparison, however, because we used pretrained features that already contained prior knowledge about cats and dogs, which competitors couldn’t use at the time.

On the positive side, by using modern deep learning techniques, we managed to reach this result using only a small fraction of the training data that was available for the competition (about 10%). There is a huge difference between being able to train on 20,000 samples compared to 2,000 samples!

Now you have a solid set of tools for dealing with image-classification problems—in particular, with small datasets.

8.4 Summary

- Convnets excel at computer vision tasks. It’s possible to train one from scratch, even on a very small dataset, with decent results.

- Convnets work by learning a hierarchy of modular patterns and concepts to represent the visual world.

- On a small dataset, overfitting will be the main problem. Data augmentation is a powerful way to fight overfitting when you’re working with image data.

- It’s easy to reuse an existing convnet on a new dataset via feature extraction. This is a valuable technique for working with small image datasets.

- As a complement to feature extraction, you can use fine-tuning, which adapts to a new problem some of the representations previously learned by an existing model. This pushes performance a bit further.